Hamlet was the only son of the King of Denmark. He loved his father and mother dearly–and was happy in the love of a sweet lady named Ophelia. Her father, Polonius, was the King’s Chamberlain.

While Hamlet was away studying at Wittenberg, his father died. Young Hamlet hastened home in great grief to hear that a serpent had stung the King, and that he was dead. The young Prince had loved his father so tenderly that you may judge what he felt when he found that the Queen, before yet the King had been laid in the ground a month, had determined to marry again–and to marry the dead King’s brother.

Hamlet refused to put off mourning for the wedding.

“It is not only the black I wear on my body,” he said, “that proves my loss. I wear mourning in my heart for my dead father. His son at least remembers him, and grieves still.”

Then said Claudius the King’s brother, “This grief is unreasonable. Of course you must sorrow at the loss of your father, but–”

“Ah,” said Hamlet, bitterly, “I cannot in one little month forget those I love.”

With that the Queen and Claudius left him, to make merry over their wedding, forgetting the poor good King who had been so kind to them both.

And Hamlet, left alone, began to wonder and to question as to what he ought to do. For he could not believe the story about the snake-bite. It seemed to him all too plain that the wicked Claudius had killed the King, so as to get the crown and marry the Queen. Yet he had no proof, and could not accuse Claudius.

And while he was thus thinking came Horatio, a fellow student of his, from Wittenberg.

“What brought you here?” asked Hamlet, when he had greeted his friend kindly.

“I came, my lord, to see your father’s funeral.”

“I think it was to see my mother’s wedding,” said Hamlet, bitterly. “My father! We shall not look upon his like again.”

“My lord,” answered Horatio, “I think I saw him yesternight.”

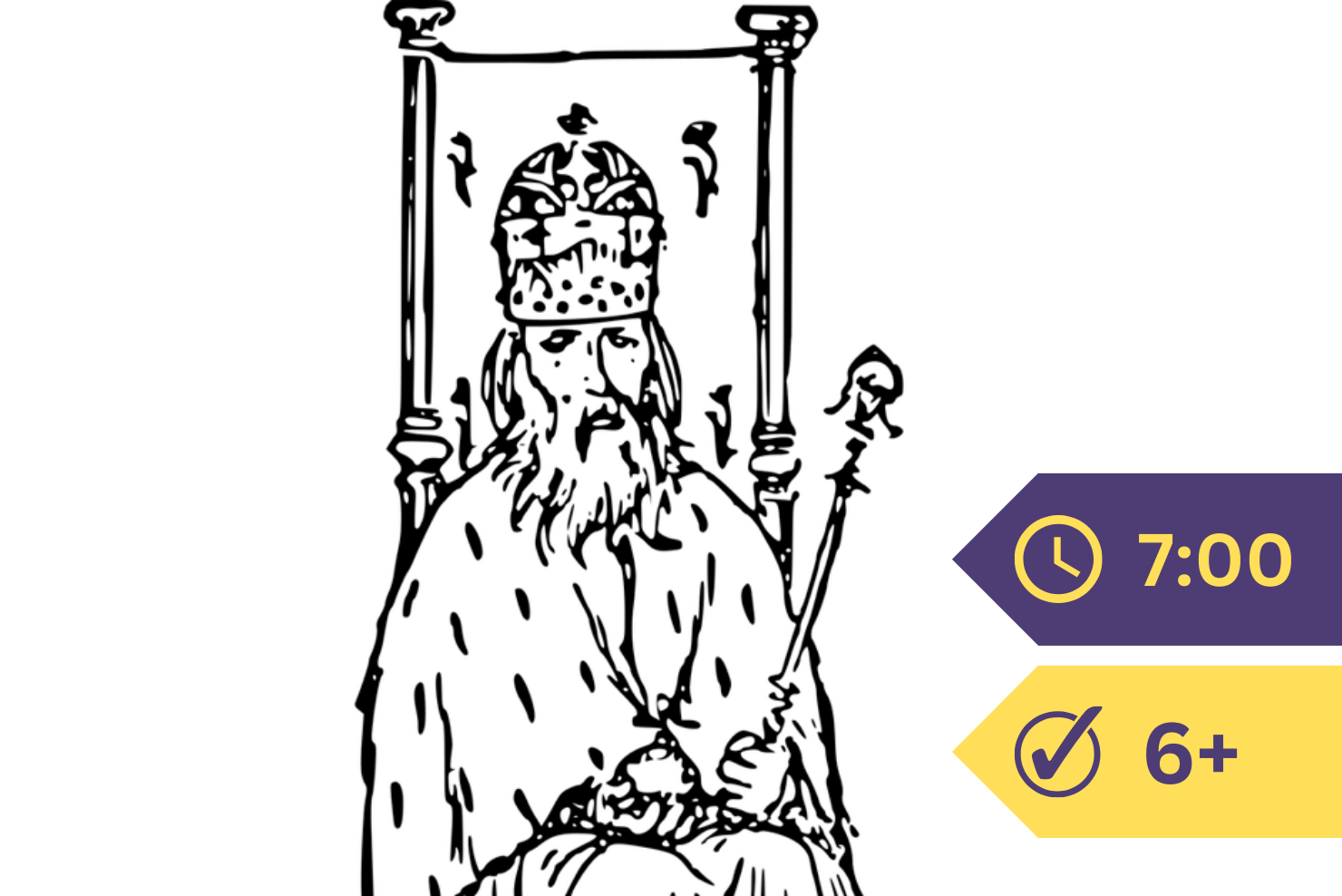

Then, while Hamlet listened in surprise, Horatio told how he, with two gentlemen of the guard, had seen the King’s ghost on the battlements. Hamlet went that night, and true enough, at midnight, the ghost of the King, in the armor he had been wont to wear, appeared on the battlements in the chill moonlight. Hamlet was a brave youth. Instead of running away from the ghost he spoke to it–and when it beckoned him he followed it to a quiet place, and there the ghost told him that what he had suspected was true. The wicked Claudius had indeed killed his good brother the King, by dropping poison into his ear as he slept in his orchard in the afternoon.

“And you,” said the ghost, “must avenge this cruel murder– on my wicked brother. But do nothing against the Queen– for I have loved her, and she is your mother. Remember me.”

Then seeing the morning approach, the ghost vanished.

“Now,” said Hamlet, “there is nothing left but revenge. Remember thee–I will remember nothing else–books, pleasure, youth–let all go–and your commands alone live on my brain.”

So when his friends came back he made them swear to keep the secret of the ghost, and then went in from the battlements, now gray with mingled dawn and moonlight, to think how he might best avenge his murdered father.

The shock of seeing and hearing his father’s ghost made him feel almost mad, and for fear that his uncle might notice that he was not himself, he determined to hide his mad longing for revenge under a pretended madness in other matters.

And when he met Ophelia, who loved him–and to whom he had given gifts, and letters, and many loving words–he behaved so wildly to her, that she could not but think him mad. For she loved him so that she could not believe he would be as cruel as this, unless he were quite mad. So she told her father, and showed him a pretty letter from Hamlet. And in the letter was much folly, and this pretty verse–

“Doubt that the stars are fire;

Doubt that the sun doth move;

Doubt truth to be a liar;

But never doubt I love.”

And from that time everyone believed that the cause of Hamlet’s supposed madness was love.

Poor Hamlet was very unhappy. He longed to obey his father’s ghost–and yet he was too gentle and kindly to wish to kill another man, even his father’s murderer. And sometimes he wondered whether, after all, the ghost spoke truly.

Just at this time some actors came to the Court, and Hamlet ordered them to perform a certain play before the King and Queen. Now, this play was the story of a man who had been murdered in his garden by a near relation, who afterwards married the dead man’s wife.

You may imagine the feelings of the wicked King, as he sat on his throne, with the Queen beside him and all his Court around, and saw, acted on the stage, the very wickedness that he had himself done. And when, in the play, the wicked relation poured poison into the ear of the sleeping man, the wicked Claudius suddenly rose, and staggered from the room–the Queen and others following.

Then said Hamlet to his friends–

“Now I am sure the ghost spoke true. For if Claudius had not done this murder, he could not have been so distressed to see it in a play.”

Now the Queen sent for Hamlet, by the King’s desire, to scold him for his conduct during the play, and for other matters; and Claudius, wishing to know exactly what happened, told old Polonius to hide himself behind the hangings in the Queen’s room. And as they talked, the Queen got frightened at Hamlet’s rough, strange words, and cried for help, and Polonius behind the curtain cried out too. Hamlet, thinking it was the King who was hidden there, thrust with his sword at the hangings, and killed, not the King, but poor old Polonius.

So now Hamlet had offended his uncle and his mother, and by bad hap killed his true love’s father.

“Oh! what a rash and bloody deed is this,” cried the Queen.

And Hamlet answered bitterly, “Almost as bad as to kill a king, and marry his brother.” Then Hamlet told the Queen plainly all his thoughts and how he knew of the murder, and begged her, at least, to have no more friendship or kindness of the base Claudius, who had killed the good King. And as they spoke the King’s ghost again appeared before Hamlet, but the Queen could not see it. So when the ghost had gone, they parted.

When the Queen told Claudius what had passed, and how Polonius was dead, he said, “This shows plainly that Hamlet is mad, and since he has killed the Chancellor, it is for his own safety that we must carry out our plan, and send him away to England.”

So Hamlet was sent, under charge of two courtiers who served the King, and these bore letters to the English Court, requiring that Hamlet should be put to death. But Hamlet had the good sense to get at these letters, and put in others instead, with the names of the two courtiers who were so ready to betray him. Then, as the vessel went to England, Hamlet escaped on board a pirate ship, and the two wicked courtiers left him to his fate, and went on to meet theirs.

Hamlet hurried home, but in the meantime a dreadful thing had happened. Poor pretty Ophelia, having lost her lover and her father, lost her wits too, and went in sad madness about the Court, with straws, and weeds, and flowers in her hair, singing strange scraps of songs, and talking poor, foolish, pretty talk with no heart of meaning to it. And one day, coming to a stream where willows grew, she tried to bang a flowery garland on a willow, and fell into the water with all her flowers, and so died.

And Hamlet had loved her, though his plan of seeming madness had made him hide it; and when he came back, he found the King and Queen, and the Court, weeping at the funeral of his dear love and lady.

Ophelia’s brother, Laertes, had also just come to Court to ask justice for the death of his father, old Polonius; and now, wild with grief, he leaped into his sister’s grave, to clasp her in his arms once more.

“I loved her more than forty thousand brothers,” cried Hamlet, and leapt into the grave after him, and they fought till they were parted.

Afterwards Hamlet begged Laertes to forgive him.

“I could not bear,” he said, “that any, even a brother, should seem to love her more than I.”

But the wicked Claudius would not let them be friends. He told Laertes how Hamlet had killed old Polonius, and between them they made a plot to slay Hamlet by treachery.

Laertes challenged him to a fencing match, and all the Court were present. Hamlet had the blunt foil always used in fencing, but Laertes had prepared for himself a sword, sharp, and tipped with poison. And the wicked King had made ready a bowl of poisoned wine, which he meant to give poor Hamlet when he should grow warm with the sword play, and should call for drink.

So Laertes and Hamlet fought, and Laertes, after some fencing, gave Hamlet a sharp sword thrust. Hamlet, angry at this treachery–for they had been fencing, not as men fight, but as they play–closed with Laertes in a struggle; both dropped their swords, and when they picked them up again, Hamlet, without noticing it, had exchanged his own blunt sword for Laertes’ sharp and poisoned one. And with one thrust of it he pierced Laertes, who fell dead by his own treachery.

At this moment the Queen cried out, “The drink, the drink! Oh, my dear Hamlet! I am poisoned!”

She had drunk of the poisoned bowl the King had prepared for Hamlet, and the King saw the Queen, whom, wicked as he was, he really loved, fall dead by his means.

Then Ophelia being dead, and Polonius, and the Queen, and Laertes, and the two courtiers who had been sent to England, Hamlet at last found courage to do the ghost’s bidding and avenge his father’s murder–which, if he had braced up his heart to do long before, all these lives had been spared, and none had suffered but the wicked King, who well deserved to die.

Hamlet, his heart at last being great enough to do the deed he ought, turned the poisoned sword on the false King.

“Then–venom–do thy work!” he cried, and the King died.

So Hamlet in the end kept the promise he had made his father. And all being now accomplished, he himself died. And those who stood by saw him die, with prayers and tears, for his friends and his people loved him with their whole hearts. Thus ends the tragic tale of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.