When these little seeds at last find a good resting place, what do you think happens to them? They grow into new plants, of course. But how does this come about? How does a seed turn into a plant?

I could hardly expect you to guess this, any more than I could have expected you to guess how the apple flower changes into the apple fruit. I will tell you a little about it; and then I hope your teacher will show you real seeds and real plants, and prove to you that what I have said is really so.

Of course, you believe already that I try to tell you the exact truth about all these things. But people far wiser than I have been mistaken in what they thought was true; and so it will be well for you to make sure, with your own eyes, that I am right in what I say.

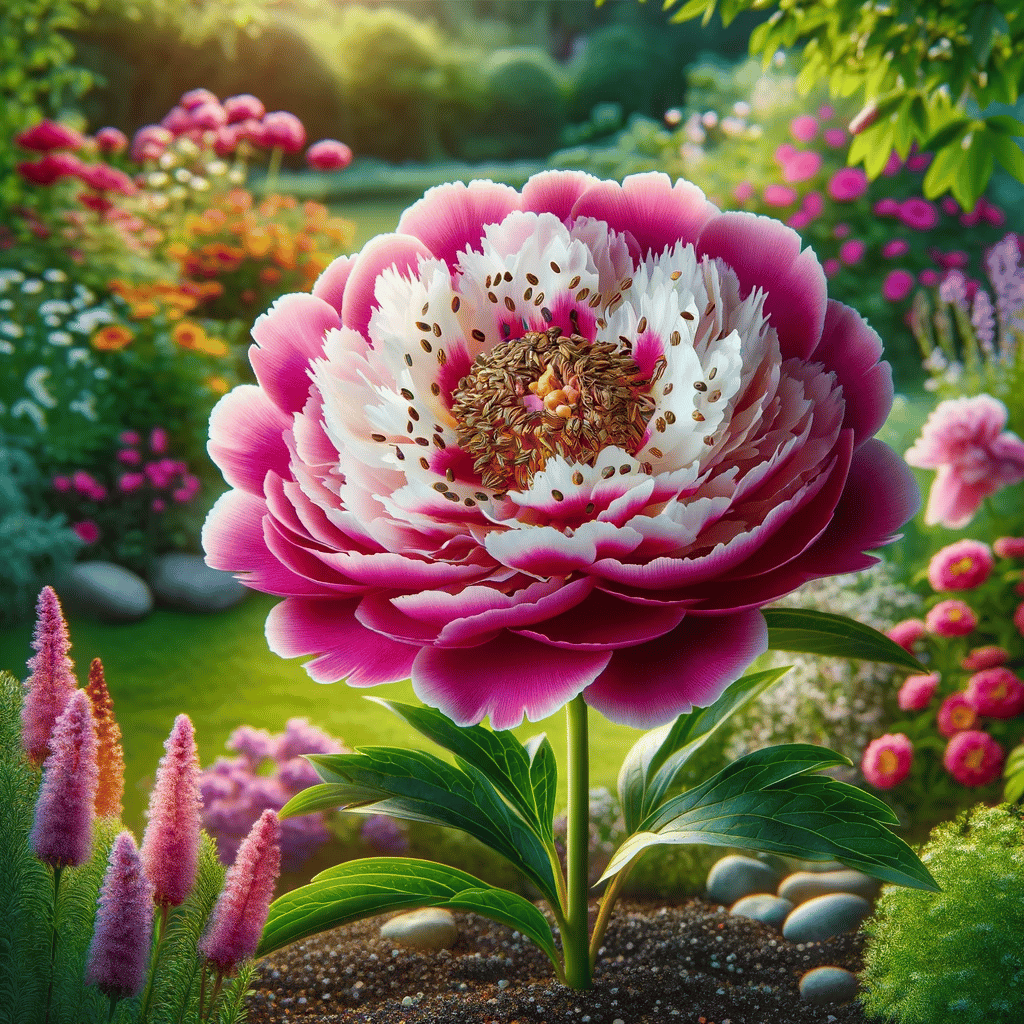

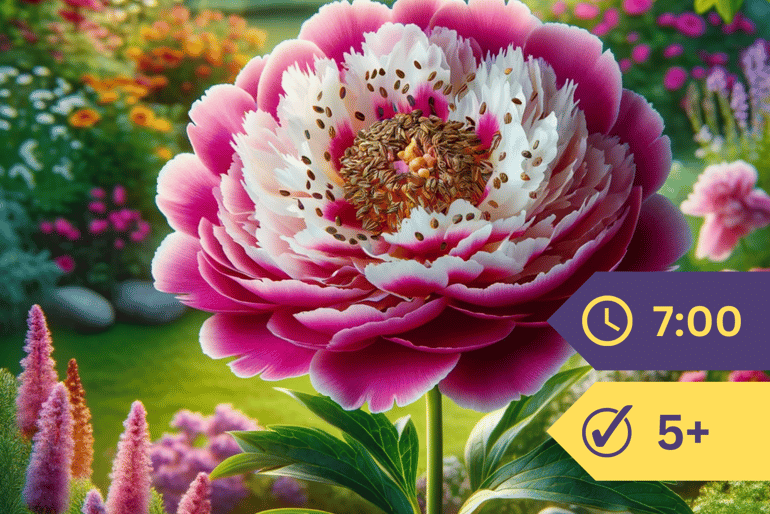

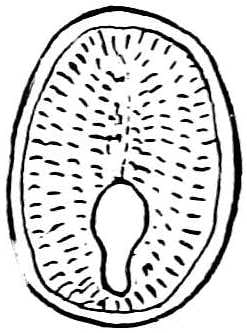

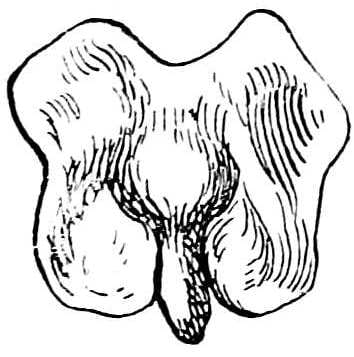

If you should cut in two the seed of that beautiful flower the garden peony, and should look at it very closely through a good magnifying glass, you would find a tiny object such as you see in the half seed shown in this picture. Both your eyes and your glass need to be very good to show you that this little object is a baby peony plant. The picture below gives the little plant as it would look if taken out of the seed.

Every ripe seed holds a baby plant; and to become a grown-up plant, it needs just what boy and girl babies need,—food and drink and air.

But shut up so tight in its seed shell, how can it get these?

Well, in this peony seed its food is close at hand. It is packed away inside the seed, all about the little plant. In the picture, everything except the little white spot, which shows the plant, is baby food,—food that is all prepared to be eaten by a delicate little plant, and that is suited to its needs just as milk is suited to the needs of your little sister or brother.

The little leaves of the baby plant take in the food that is needed to make it grow fat and strong.

Now, how does the baby plant get water to drink?

I have asked your teacher to soak over night some peas that have been dried for planting, and to bring to school to-day a handful of these, and also a handful which have not been soaked. She will pass these about, and you can see how different the soaked ones are from the others. Those that have not been in the water look dried and wrinkled and old, almost dead in fact; while those which have been soaked are nearly twice as large. They look fat, and fresh, and full of life. Now, what has happened to them?

Why, all night long they have been sucking in water through tiny openings in the seed shell; and this water has so refreshed them, and so filled the wrinkled coats and swelled them out, that they look almost ready to burst.

So you see, do you not, how the water manages to get inside the seed so as to give the baby plant a drink?

Usually it is rather late in the year when seeds fall to the earth. During the winter the baby plant does not do any drinking; for then the ground is frozen hard, and the water cannot reach it. But when the warm spring days come, the ice melts, and the ground is full of moisture. Then the seed swells with all the water it sucks in, and the baby plant drinks, drinks, drinks, all day long.

You scarcely need ask how it keeps warm, this little plant. It is packed away so snugly in the seed shell, and the seed shell is so covered by the earth, and the earth much of the time is so tucked away beneath a blanket of snow, that usually there is no trouble at all about keeping warm.

But how, then, does it get air?

Well, of course, the air it gets would not keep alive a human baby. But a plant baby needs only a little air; and usually enough to keep it in good condition makes its way down through the snow and earth to the tiny openings in the seed shell. To be sure, if the earth above is kept light and loose, the plant grows more quickly, for then the air reaches it with greater ease.

So now you see how the little plant inside the peony seed gets the food and drink and air it needs for its growth.

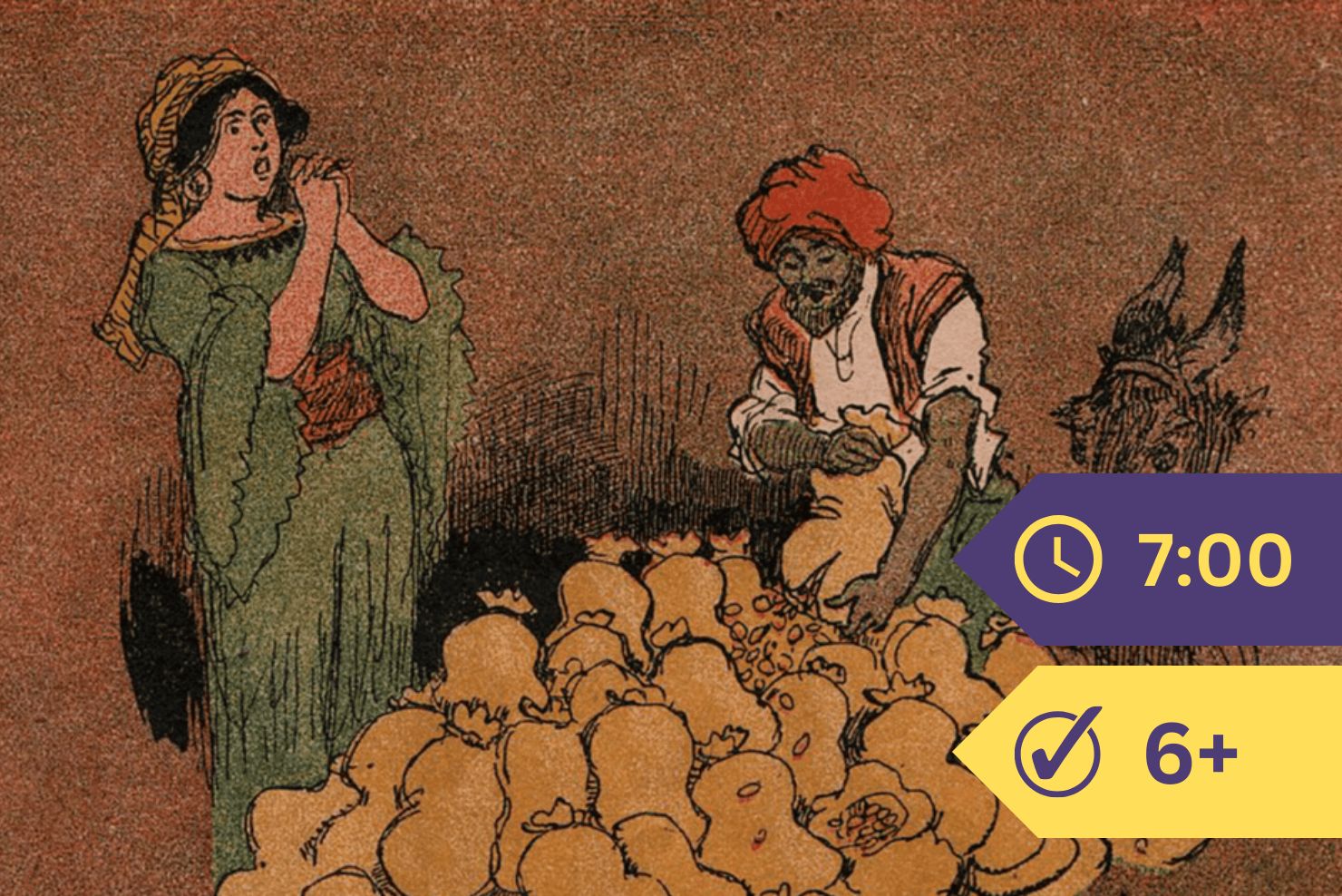

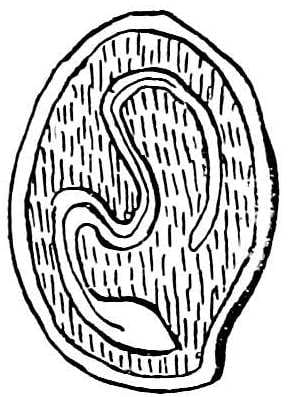

In the picture above you get a side view of the baby plant of the morning-glory, its unripe seed being cut in two. As you look at it here, its queer shape reminds you of an eel. But if instead of cutting through the seed, you roll it carefully between your fingers, and manage to slip off its coat, and if then you take a pin and carefully pick away the whitish, jelly-like stuff which has been stored as baby food, you will find a tiny green object which through a magnifying glass looks like the next picture. The narrow piece pointing downward is the stem from which grows the root. Above this are two leaves.

This baby plant is a very fascinating thing to look at. I never seem to tire of picking apart a young seed for the sake of examining through a glass these delicate bright-green leaves. It seems so wonderful that the vine which twines far above our heads, covered with glorious flowers, should come from this green speck.

As this morning-glory is a vine which lives at many of your doorsteps, I hope you will not fail to collect its seeds, and look at their baby plants. When these are very young, still surrounded by a quantity of baby food, you will not be able to make them out unless you carry them to your teacher and borrow her glass; but when the seed is ripe, and the little plant has eaten away most of the surrounding food, it grows so big that you can see it quite plainly with your own eyes.