Some time ago we learned that the little root hairs, by means of their acid, are able to make a sort of broth from the earthy materials which they could not swallow in a solid state.

But before this broth is really quite fit for plant food, it needs even more preparation.

Why do we eat and drink, do you suppose?

“Because we are hungry.” That is the direct reason, of course. But we are made hungry so that we shall be forced to eat; for when we eat, we take into our bodies the material that is needed to build them up,—to feed the cells which make the flesh and bone and muscle.

And this is just why the plant eats and drinks. It needs constantly fresh nourishment for its little cells, so that these can live, and grow strong enough to make the new cells which go to form, not bone and flesh and muscle, as with you children, but fresh roots and stem and leaves and flowers and fruits.

If these little cells were not fed, they would die, and the plant would cease to live also.

And now what do you think happens to the broth that has been taken in from the earth by the root hairs?

As we have said, this broth needs a little more preparation before it is quite fit for plant food. What it really wants is some cooking.

Perhaps you can guess that the great fire before which all plant food is cooked is the sun.

But how are the hot rays of the sun to pierce the earth, and reach the broth which is buried in the plant’s root?

Of course, if it remains in the root, the earth broth will not get the needed cooking. It must be carried to some more get-at-able position.

Now, what part of a plant is usually best fitted to receive the sun’s rays?

Its leaves, to be sure. The thin, flat leaf blades are spread out on all sides, so that they fairly bathe themselves in sunshine.

So if the broth is to be cooked in the sun, up to the leaves it must be carried.

And how is this managed? Water does not run uphill, as you know. Yet this watery broth must mount the stem before it can enter the leaves.

Water does not run uphill ordinarily, it is true; yet, if you dip a towel in a basin of water, the water rises along the threads, and the towel is wet far above the level of the basin.

And if you dip the lower end of a lump of sugar in a cup of coffee, the coffee rises in the lump, and stains it brown.

And the oil in the lamp mounts high into the wick.

Perhaps when you are older you will be able somewhat to understand the reason of this rise of liquid in the towel, in the lump of sugar, in the lamp wick. The same reason accounts partly for the rise of the broth in the stem. But it is thought that the force which sends the oil up the wick would not send the water far up the stem. And you know that some stems are very tall indeed. The distance, for example, to be traveled by water or broth which is sucked in by the roots of an oak tree, and which must reach the top-most leaves of the oak, is very great.

Yet the earth broth seems to have no difficulty in making this long, steep climb.

Now, even wise men have to do some guessing about this matter, and I fear you will find it a little hard to understand.

But it is believed that the roots drink in the earth broth so eagerly and so quickly, that before they know it they are full to overflowing. It is easier, however, to enter a root than it is to leave it by the same door; and the result is, that the broth is forced upward into the stem by the pressure of more water or broth behind.

Of course, if the stem and branches and leaves above are already full of liquid, unless they have some way of disposing of the supply on hand, they cannot take in any more; and the roots below would then be forced to stop drinking, for when a thing is already quite full to overflowing, it cannot be made to hold more.

But leaves have a habit of getting rid of what they do not need. When the watery broth is cooked in the sun, the heat of the sun’s rays causes the water to pass off through the little leaf mouths. Thus the broth is made fit for plant food, and at the same time room is provided for fresh supplies from the root.

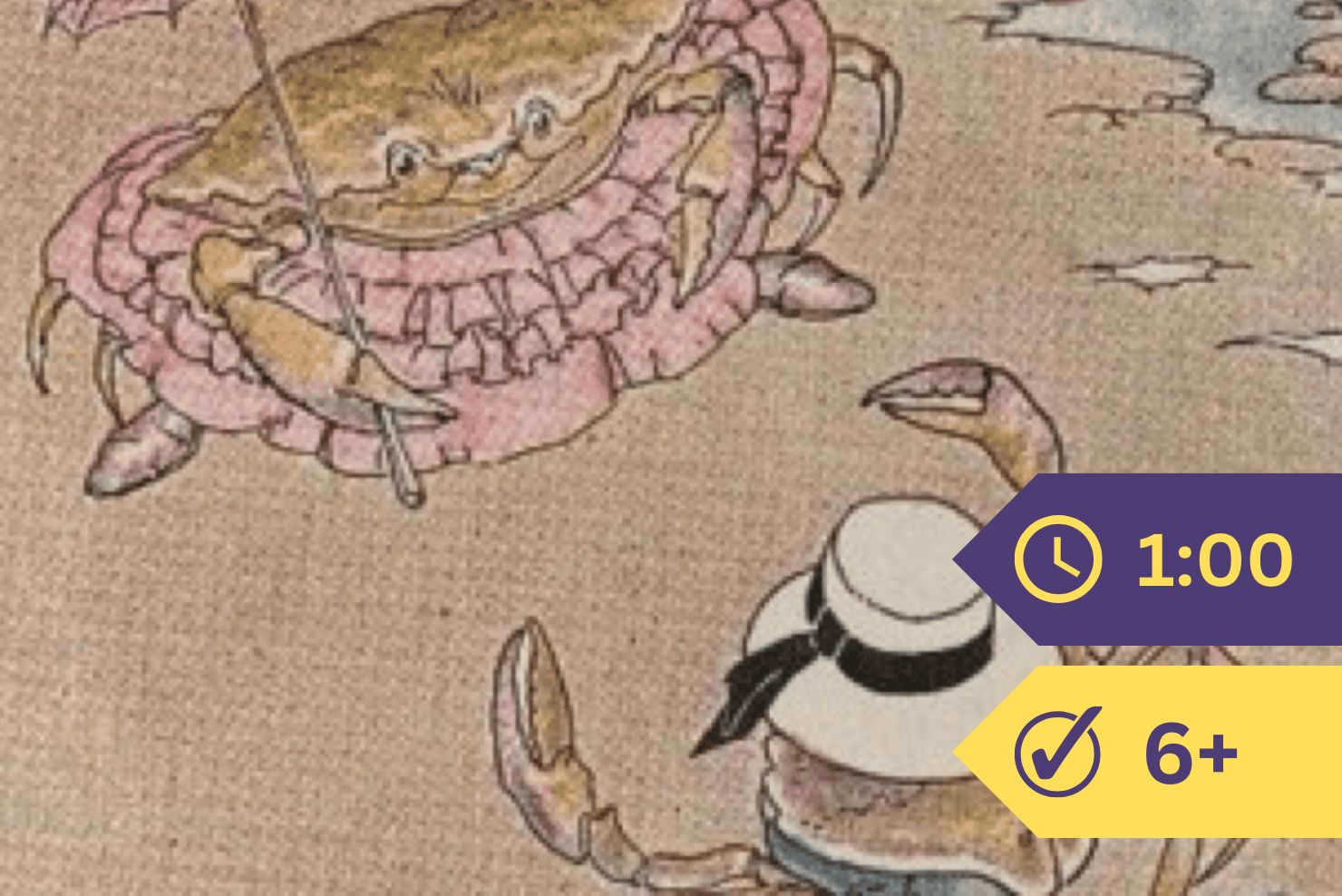

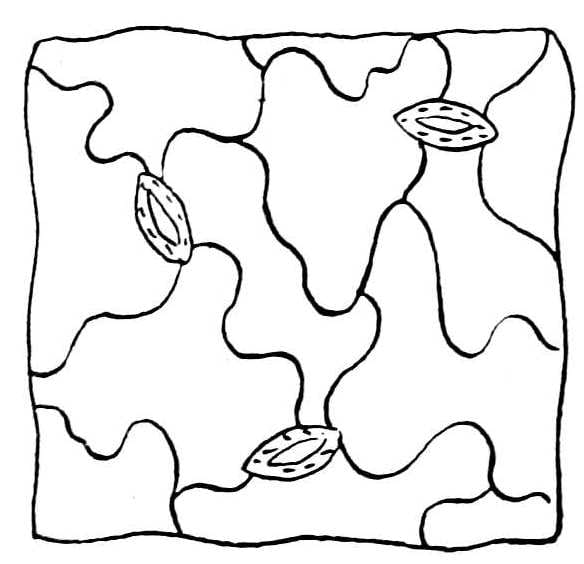

If you should examine the lower side of a leaf through a microscope, you would find hundreds and thousands of tiny mouths, looking like the little mouths in this picture.

Some of the water from the earth broth is constantly passing through these mouths out of the plant, into the air.