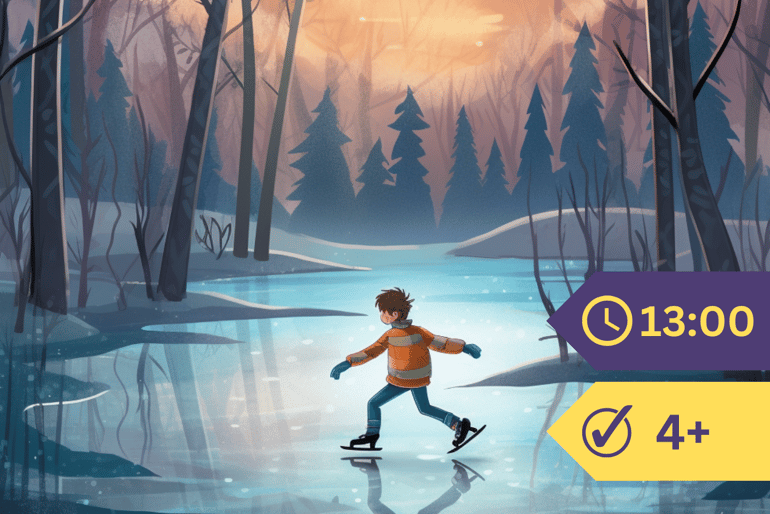

There was once a little boy to whom Santa Claus brought a pair of skates at Christmas. And, of course, that boy, as soon as he saw the shiny, steel runners, wished that the pond would freeze over so that he might try his new playthings.

“When do you s’pose there’ll be skating?” he asked his mother again and again, for, as yet, there was only a “skim” of ice on the pond.

“Oh, pretty soon,” his mother would answer. “You mustn’t go skating when the ice is too thin, you know. If you did you would break through, into the cold water.”

“And that would spoil my skates, wouldn’t it?” asked the boy.

“Yes, but besides that you might be drowned, or catch cold and be very ill,” Mother said. “So keep off the ice with your new skates until the pond has frozen good and thick.”

“Yes’m, I will,” promised the little boy, and, really, he meant to keep his word. But as the days passed, and the weather was not quite cold enough to freeze thick ice, the little boy became tired of waiting.

Every chance he had, after school, he would go down to the edge of the pond, and throw stones on the ice to see how thick it was. Often the stones would break through, and fall into the cold, black water with a “thump!” Then the boy would know the ice was not thick enough.

“I don’t want to fall through like a stone,” he would say, and back to his house he would go with his new skates dangling and jingling at his back, over which they were hung by a strap.

But one day, when the boy threw a large stone on the ice of the pond, instead of breaking through, the rock only made a dent and stayed there.

“Oh, hurray!” cried the boy. “I guess it’s strong enough to hold me now! I’m going skating!”

However, first he started to walk on the edge of the ice near the shore, and when he did so, and heard cracking sounds, he jumped quickly back.

“I guess I’d better not try it yet,” said the boy to himself. “I’ll wait a little while until it freezes harder.”

So he sat down by the edge of the pond to wait for the ice to freeze harder. But as he sat there, and saw how white and shiny it was, and as he looked at his new skates, which he had only put on in the house, that boy couldn’t wait another minute.

He walked along the shore a little farther, to a place where the ice seemed more hard and shiny and there, after throwing some stones, and venturing out a little way, finding that there was no cracking sound, the little boy made up his mind to try to skate. There was no one else on the pond—no other boys and girls, and it was a bit lonesome. But the boy was so eager to try his new skates that he did not think of this.

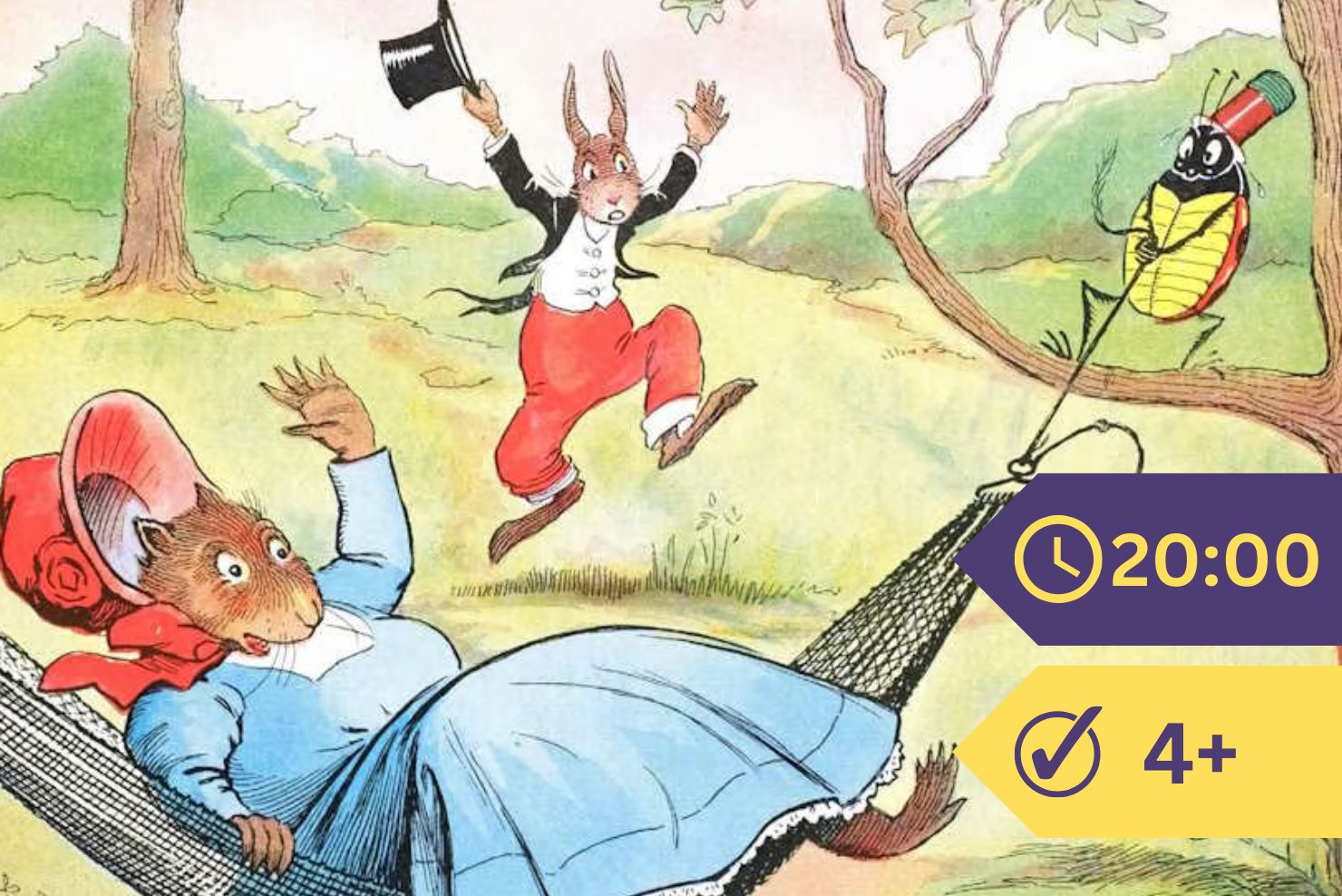

Down he sat on the ground, and began putting on his Christmas skates. And it was just about this time that Nurse Jane Fuzzy Wuzzy, Uncle Wiggily’s muskrat lady housekeeper, happened to look out of the window of the hollow stump bungalow. The bunny’s bungalow was so hidden in the woods, near the pond, that few boys or girls ever saw the queer little house. But Uncle Wiggily could see them, as they came to the woods winter and summer, and often he was able to help them.

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed Nurse Jane, as she looked out of the window a second time.

“What’s the matter?” asked Uncle Wiggily, who was just finishing his breakfast of lettuce bread and carrot coffee, with some turnip marmalade.

“Why, there’s a boy—a real boy and not one of the animal chaps—getting ready to go skating!” said the muskrat lady, for she could see the boy putting on his skates.

“That ice isn’t thick enough for real boys or girls to skate on,” the bunny gentleman said. “It would be all right for Sammie Littletail, or Johnnie or Billie Bushytail, but real boys are too heavy—much heavier than my nephew Sammie the rabbit, or than the bushytail squirrel chaps.”

“Well, this boy is going on all the same,” cried Nurse Jane. “And I know he’ll break through, and he’ll frighten his mother into a conniption fit!”

“That will be too bad!” exclaimed Uncle Wiggily, as he wiped a little of the turnip marmalade off his whiskers, where it had fallen by mistake. “I must try to save him if he does fall in!”

“It would be better to keep him from going on the ice,” spoke Nurse Jane. “Safety first, you know!”

“If I could speak boy language I’d hop down there and tell him the ice is too thin,” answered Uncle Wiggily. “But though I know what the boys and girls say, I cannot, myself, speak their talk. However, I think I know a way to save this boy, if he happens to break through the ice.”

“Well, he’s almost sure to break through,” declared Miss Fuzzy Wuzzy, “so you’d better hurry.”

“No sooner said than done!” exclaimed Uncle Wiggily, and, catching up his red, white and blue striped rheumatism crutch, and putting on his fur cap (for the day was cold), away the bunny hopped from his hollow stump bungalow.

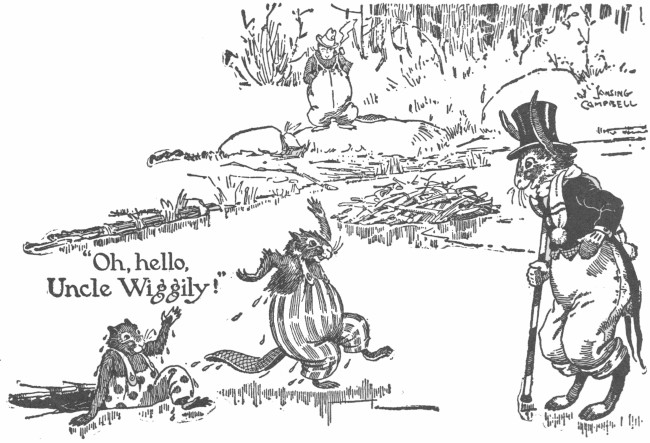

Instead of going to the place where the boy, with his skates fastened on his shoes, was about to try the ice, the bunny gentleman went to the house of some friends of his. The house would seem queer to you, for all it looked like was a pile of sticks half buried in the frozen pond.

But in this house lived a family of beavers—queer animals whose fur is so warm and thick that they can swim in ice water and not feel chilly. In fact the beavers had to dive down under the ice and water to get into their winter home.

“Are Toodle and Noodle in the house?” asked Uncle Wiggily, as he reached the stick-house. On shore, not far from it, was Grandpa Whackum, the old beaver gentleman, with his broad, flat tail.

“Why, yes, Toodle and Noodle are inside,” answered Grandpa Whackum. “Shall I call them out?”

“If you please,” spoke Uncle Wiggily. “I want them to come and help me save a boy who, I think, is going to break through the thin ice with his new skates.”

“That will be too bad!” exclaimed Grandpa Whackum. Then with his broad tail he pounded or “whacked” on the ground, and soon up through a hole in the ice came swimming Toodle and Noodle Flat-Tail, the two beaver boys.

“Oh, hello, Uncle Wiggily!” they called. “We’re glad to see you!”

“Hello!” answered the bunny gentleman. “Will you come with me, and help save a real boy?”

“Of course,” said Toodle, shaking off some ice water from his fur coat.

“He won’t try to catch us, will he?” asked Noodle.

“I think not,” the bunny gentleman replied. “If what I think is going to happen, does really happen, that boy will be too surprised to catch anything but a cold! Come along, beaver chaps!”

So Toodle and Noodle, wet and glistening from having dived out of their house, and down under water to come up through the hole in the ice, followed Uncle Wiggily. The sun and wind soon dried their fur.

“There’s the boy,” said Uncle Wiggily, as he and the beaver chaps reached the edge of the pond. “He’s skating on thin ice. He’ll go through in a minute!”

And, surely enough, hardly had the bunny spoken than there was a cracking sound, the ice broke beneath the boy’s feet and into the dark, cold water he fell.

“Oh! Oh!” cried the boy. “Help me, somebody! Oh! Oh!”

“Ha! It’s a good thing Nurse Jane saw him!” said Uncle Wiggily. “Quick now, Toodle and Noodle! I brought you along because you have such good, sharp teeth—much sharper and better than mine are for gnawing down trees. I can gnaw off the bark, but you can nibble all the way through a tree and make it fall.”

“Is that what you want us to do?” asked Toodle.

“Yes,” answered Uncle Wiggily. “We’ll go close to shore, where the boy has fallen in. Near him is a tree. You’ll gnaw that so it will fall outward across the ice, and he can reach up, take hold of it and pull himself out of the hole.”

By this time the poor boy was floundering around in the cold water. He tried to get hold of the edges of the ice around the hole through which he had fallen, but the ice broke in his hands.

“Help! Help!” he cried.

“We’re going to help you,” answered Uncle Wiggily, but, of course, he spoke animal language which the boy did not understand. But Toodle and Noodle understood, and quickly running to the edge of the shore they gnawed and gnawed and gnawed very extra fast at an overhanging tree until it began to bend and break. Uncle Wiggily gnawed a little, also, to help the beaver boys.

Then, just as the real boy was almost ready to sink down under water, the tree fell on the ice, some of its branches close enough so the boy skater could grasp them.

“Oh, now I can pull myself out!” he said. “This tree fell just in time! Now I’ll be saved!”

He did not know that Uncle Wiggily and the beaver boys had gnawed the tree down, making it fall just in the right place at the right time. For the boy was so frightened at having broken through the ice, that he never noticed the bunny gentleman and the beaver boys on shore.

He caught hold of the tree branches in his cold fingers, pulled himself up out of the water, that boy did; and to shore. Then as he sat down, all wet and shivering, to take off his skates, so he could run home, Uncle Wiggily called to Toodle and Noodle:

“Come on, beaver boys! Our work is done! We have saved that boy, and I hope he never again tries to skate on thin ice.”

Then Uncle Wiggily hopped toward his hollow stump bungalow, and the beaver boys slid on the ice, near shore, toward their own stick-house, for the pond was frozen hard and thick enough to hold them. And the boy ran home as fast as he could, and drank hot lemonade so he wouldn’t catch cold.

He did get the snuffles, but of course that couldn’t be helped, and it wasn’t much for falling through the ice; was it?

“You never should have gone skating until the pond was better frozen,” his mother said.

“I know it,” the boy answered. “But wasn’t it lucky that tree fell when it did?”

“Very lucky!” agreed his mother. And neither the boy nor his mother knew that it was Nurse Jane, Uncle Wiggily and the beaver boys who had caused the tree to topple over just in time.