When you go for a walk in the country, what do you see all about you?

“Cows and horses, and chickens and birds, and trees and flowers,” answers some child.

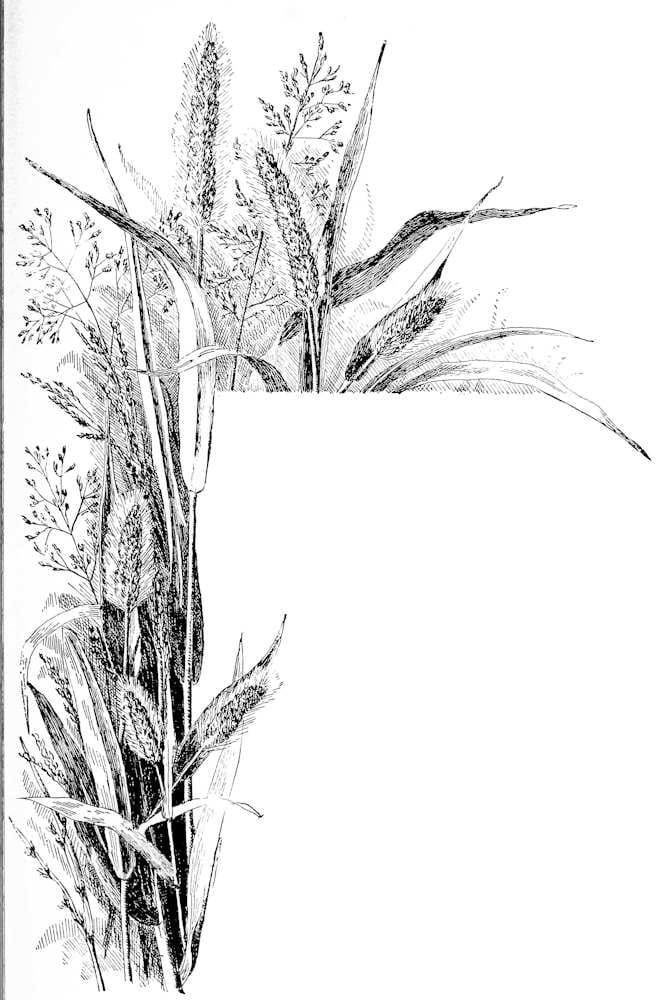

Yes, all of these things you see. But of the trees and plants you see even more than of the horses and cows and birds. On every side are plants of one kind or another. The fields are full of grass plants. The woods are full of tree plants. Along the roadside are plants of many varieties.

Now, what are all these plants trying to do? “To grow,” comes the answer. To grow big and strong enough to hold their own in the world. That is just what they are trying to do.

Then, too, they are trying to flower.

“But they don’t all have flowers,” objects one voice.

You are right. They do not all have flowers; but you would be surprised to know how many of them do. In fact, all of them except the ferns and mosses, and a few others, some of which you would hardly recognize as plants,—all of them, with these exceptions, flower at some time in their lives.

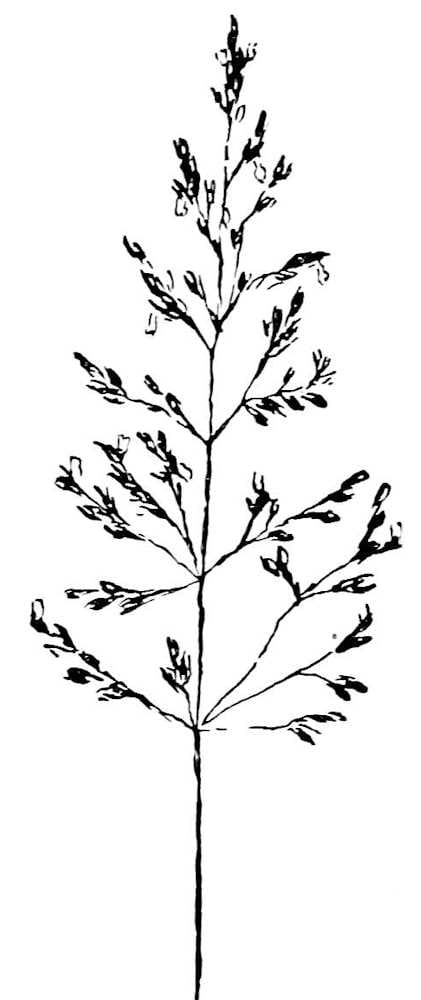

All the trees have flowers, and all the grasses; and all those plants which get so dusty along the roadside, and which you call “weeds,”—each one of these has its own flower. This may be so small and dull-looking that you have never noticed it; and unless you look sharply, perhaps you never will. But all the same, it is a flower.

But there is one especial thing which is really the object of the plant’s life. Now, who can tell me this: what is this object of a plant’s life?

Do you know just what I mean by this question? I doubt it; but I will try to make it clear to you.

If I see a boy stop his play, get his hat, and start down the street, I know that he has what we call “an object in view.” There is some reason for what he is doing. And if I say to him, “What is the object of your walk?” I mean, “For what are you going down the street?” And if he answers, “I am going to get a pound of tea for my mother,” I know that a pound of tea is the object of his walk.

So when I ask what is the object of a plant’s life, I mean why does a plant send out roots in search of food, and a stem to carry this food upward, and leaves to drink in air and sunshine? What is the object of all this?

A great many people seem to think that the object of all plants with pretty flowers must be to give pleasure. But these people quite forget that hundreds and thousands of flowers live and die far away in the lonely forest, where no human eye ever sees them; that they so lived and died hundreds and thousands of years before there were any men and women, and boys and girls, upon the earth. And so, if they stopped long enough quietly to think about it, they would see for themselves that plants must have some other object in life than to give people pleasure.

But now let us go back to the tree from which we took this apple, and see if we can find out its special object.

“Why, apples!” some of you exclaim. “Surely the object of an apple tree is to bear apples.”

That is it exactly. An apple tree lives to bear apples.

And now why is an apple such an important thing? Why is it worth so much time and trouble? What is its use?

“It is good to eat,” chime all the children in chorus.

Yes, so it is; but then, you must remember that once upon a time, apple trees, like all other plants and trees, grew in lonely places where there were no boys and girls to eat their fruit. So we must find some other answer.

Think for a moment, and then tell me what you find inside every apple.

“Apple seeds,” one of you replies.

And what is the use of these apple seeds?

“Why, they make new apple trees!”

If this be so, if every apple holds some little seeds from which new apple trees may grow, does it not look as though an apple were useful and important because it yields seeds?

And what is true of the apple tree is true of other plants and trees. The plant lives to bear fruit. The fruit is that part of the plant which holds its seeds; and it is of importance for just this reason, that it holds the seeds from which come new plants.