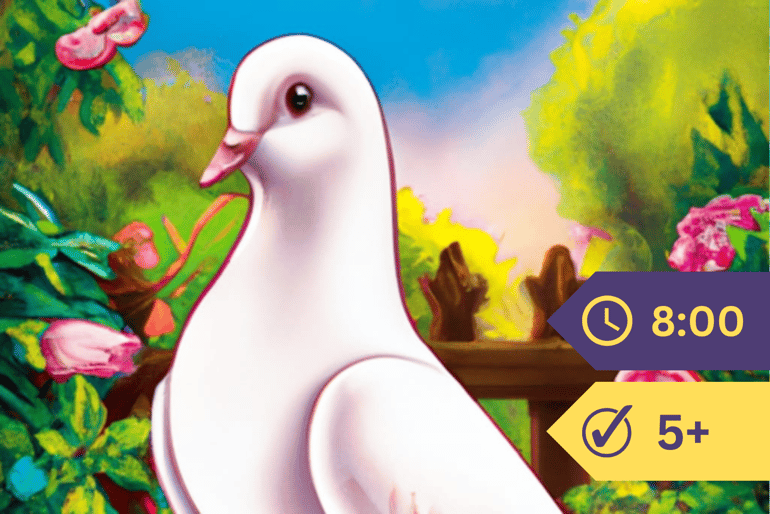

“I wonder why I am not wise!” said the little white fantail pigeon, sadly. “It seems to me I am not good for anything at all. The hens lay eggs for our mistress’s breakfast; the cow gives milk to drink and to be made into butter and cheese; the turkey will be fatted for Christmas, he says, and will be served on a big dish, with a string of sausages all round him; that will be grand! The pigs will be made into pork, but I am good for nothing. The thrush and the blackbird can sing beautifully, and the owl is wiser than all the other birds. I cannot sing and I am not at all wise. Ginger, the cat, catches the rats and mice; Monarch, the dog, guards the house. But I cannot catch rats and mice, and how could a pigeon keep guard?”

Poor little white pigeon! What was she to do? I am sure you must feel sorry for her. It is so very sad to be of no use in the world.

“I will go to the owl,” said she. “He is the wisest of all the birds. Perhaps he will teach me how to be of use.”

The owl lived in a hollow tree behind the farmyard. All day long he sat in his tree and blinked, for the sunshine hurt his eyes. That was because he was so wise, the other birds said. But when the sun went down and the world grew dark and still the owl came out from his hollow tree and flew about. He had a hooked beak and his eyes were large and round; he looked very solemn and severe, as was proper for the wisest of all the birds.

The white pigeon flew up to the hollow tree and bent her head humbly before the owl. The wise old bird blinked twice, but said nothing, because his words were so precious.

“Pray, sir,” said the pigeon, “may I speak to you?”

The owl blinked again, which if it did not mean “Yes,” at any rate did not mean, “no.”

So the pigeon went on: “Sir, you are very wise and I am very foolish. I am very unhappy because I know nothing and am good for nothing. Pease, sir, will you help me.”

The owl said nothing at all for a long time. The little white pigeon sat on a bough and waited. She said to herself: “He is slow, but that is certainly because he is so kind as to think very hard about some way to help me.”

So she waited patiently, long past the time when Jeggo gave all the birds in the farmyard their supper.

Then the sun went down, and the owl opened his large, round eyes and looked it the little white pigeon.

“Now,” said she, “he is going to speak”, and her heart beat fast with hope and excitement.

“I am wise,” said the owl, “you are foolish.”

Then he waited so long that the little pigeon ventured to put him in mind that he was speaking. “Yes, sir,” said she, “what can I do?”

“You must make the best of it,” said the owl, and spreading his large, browny-white wings he flew away into the darkness, calling out: “Too-whit, too-whoo.”

“He has certainly much wisdom,” said the little white pigeon. “But I do not see what is the good of it, if he keeps it all for himself like that. I want to know how to make the best of it.” And home she went again feeling sadder than ever.

Next day the little white pigeon was still very miserable, and instead of flying down as usual when her mistress came into the yard, she hid in a comer and hung her head. So the mistress went away, feeling sad and anxious; for she thought one of her pets was lost. Now the old drake had a very kind heart, and watched over all the animals in the farmyard. He knew that the little white pigeon was unhappy, and made up his mind to find out what was amiss, and set it right if possible. He was a clever old bird, and had seen a deal of the world, for he was nearly three years old.

He sent a message to the pigeon to say he wanted to see her, and she came at once. No one ever thought of disobeying the old drake.

“What is wrong with you, little pigeon?” said he, kindly. “The sun shines; peas and Indian com are plentiful, and you are not moulting; yet for three days you have done nothing but mope and look miserable. Come, now, and tell me what is the matter.”

“I am of no use in the world,” said the little pigeon, sadly. “All the other birds and animals are good for something, but I am good for nothing.”

“Oh! Silly bird,” said the old drake. “How can you say you are of no use in the world? Everything that is made is, and must be, of some use in the world. Some are strong and can do much work, like Short, the horse who draws the heavy cart. Some have the gift of teaching others, and that is what they are good for. Some have beautiful voices to listen to, and others beautiful feathers to look at. It is true that the turkey is good to eat and that the hen can lay eggs; it is true that the owl is wise and the blackbird can sing; but which of them all has such a pretty white tail and such nice pink feet as you?”

“I forgot all about my tail,” said the little pigeon.

“Just so,” said the old drake. “You forgot what you had, in fretting for what you have not. Nay, you even neglected your gift and let your pretty white tail get all dirty and crumpled. So it happened that our mistress went away sad this morning, because her little white bird did not come to greet her. Go away home, little pigeon, and do not be miserable any more. Make the best of what you can do, and never mind the things you cannot do.”

Then the little pigeon thanked the old drake for his good advice. She went home and put her feathers tidy, and I need hardly tell you that next day the mistress did not look in vain for her pretty, white pet.