Once upon a time, a King looked from his window at evening and seeing a rainbow in the sky, he said, “There will be rain tomorrow.”

“Nay, nay, Your Majesty,” cried all his counsellors. “A rainbow at morning is the shepherd’s warning, but a rainbow at night betokens fair skies.”

Yet, as fortune would have it, their sign failed, and they woke next morn to hear rain on the roof.

The King was mightily pleased with himself and his wisdom. Nor was it long before he began to think that if he knew more than his counsellors about one thing, he was likely to know more about other matters also.

“And if I know more than they, why have counsellors?” he asked. And in spite of all they could say or do, he sent them packing off with their law books and seals and keys and quills. There was not even so much as an ink-horn left behind them.

“A good riddance,” said the King. ‘Now I shall set my kingdom to rights;’ and having none to say “Nay, Your Majesty,” or “Yea, Your Majesty,” he soon had everything by the ears.

He told the royal cook how many plums to put in the pudding, and the court barber how many hairs would make a wig. He bade the clock-makers have their clocks say something other than “Tick-tock,” and he ordered old and young alike to bed when the sun went down. The business of the candlestick-maker was entirely ruined!

Every day the King issued new decrees changing this and changing that, till it was no wonder that there were troubled hearts and long faces in his kingdom or that men went about, telling of their trials.

Each one had a grievance of his own:

“He has changed wash-day,” cried the washerwomen.

“We must count our every stitch,” said the tapestry-workers.

“He is taking Christmas from the calendar,” mourned the parson.

“Let us march in a body to the palace and demand our liberties again,” said the blacksmith.

“Nay, let us send a writing,” said the clerk who liked to have things set down in black and white.

And the clerk having the last word, a petition was drawn up in fair script to put the whole matter of the people and their rights before the King.

When the petition reached the palace, the King was teaching the royal bed-makers how to make beds, and he was ill-pleased at the interruption. He was less pleased when he read what the people wished and the clerk had written.

“I will teach them how to interfere with me,” he stormed. And he sent a herald out to shout his royal mandate at every corner. “Hark ye! Hear ye!” the herald cried. “This says our wise and gracious King! If any man among you, rich or poor or high or low, can put a question forth to which the King has no reply, or if the King make an answer and the answer be not right, then shall the counsellors be called again and all things shall be as in days gone by.

But hark ye! Hear ye! If any man, of high degree or low, or rich, or poor, shall put a question to the King to which the King has an answer and that answer is right, then shall the asker’s head adorn the city’s walls and on his body carrion crows shall feast. And from that day the King shall rule alone as now. Hark ye! Hear ye!”

At the King’s cross and the church door, in the public square and the market place, the herald cried, and the people heard. Nothing else was talked of anywhere but the King’s proclamation; and at last the parson bade one and all assemble in the churchyard at a certain hour, that they might put their heads together concerning the question. And at the appointed time, there was a great gathering, and much talking, though to little purpose.

Some professed good courage but had no question for the King; some had a question, but no courage, and some there were with neither courage nor question who passed judgment on all that others said.

“If I had a question, I would ask it,” cried an apprentice lad. “Then here is one,” said his fellow. “How many stars are in the sky? Nobody knows that.”

“Then if the King has an answer, who can say if he be right or wrong?” objected one who heard.

“Here is a question and an answer, too,” spoke out a lass. “What traveler goes by day and night, yet never leaves his bed? A river.”

“Nay, but if you have the answer, why not the King also?” cried a good dame.

And so it went till faces grew longer and hearts heavier, and what would have been done ’twere hard to tell had it not been for a little Tailor who had sat through all the talk, listening and saying nothing. Nobody knew he was there until, of a sudden, he piped up:

“I will put a question to the King.”

Serious though the matter was, none could keep from laughing at the little Tailor’s offer, and a wag among the crowd sang out:

“There was a doughty Tailor, No bigger than a flea; Though all the world should quail and fail, ‘I’m not afraid,’ quoth he.”

But the little Tailor was not to be abashed by jests nor teasing, and what his question was, he would not tell though the parson himself asked.

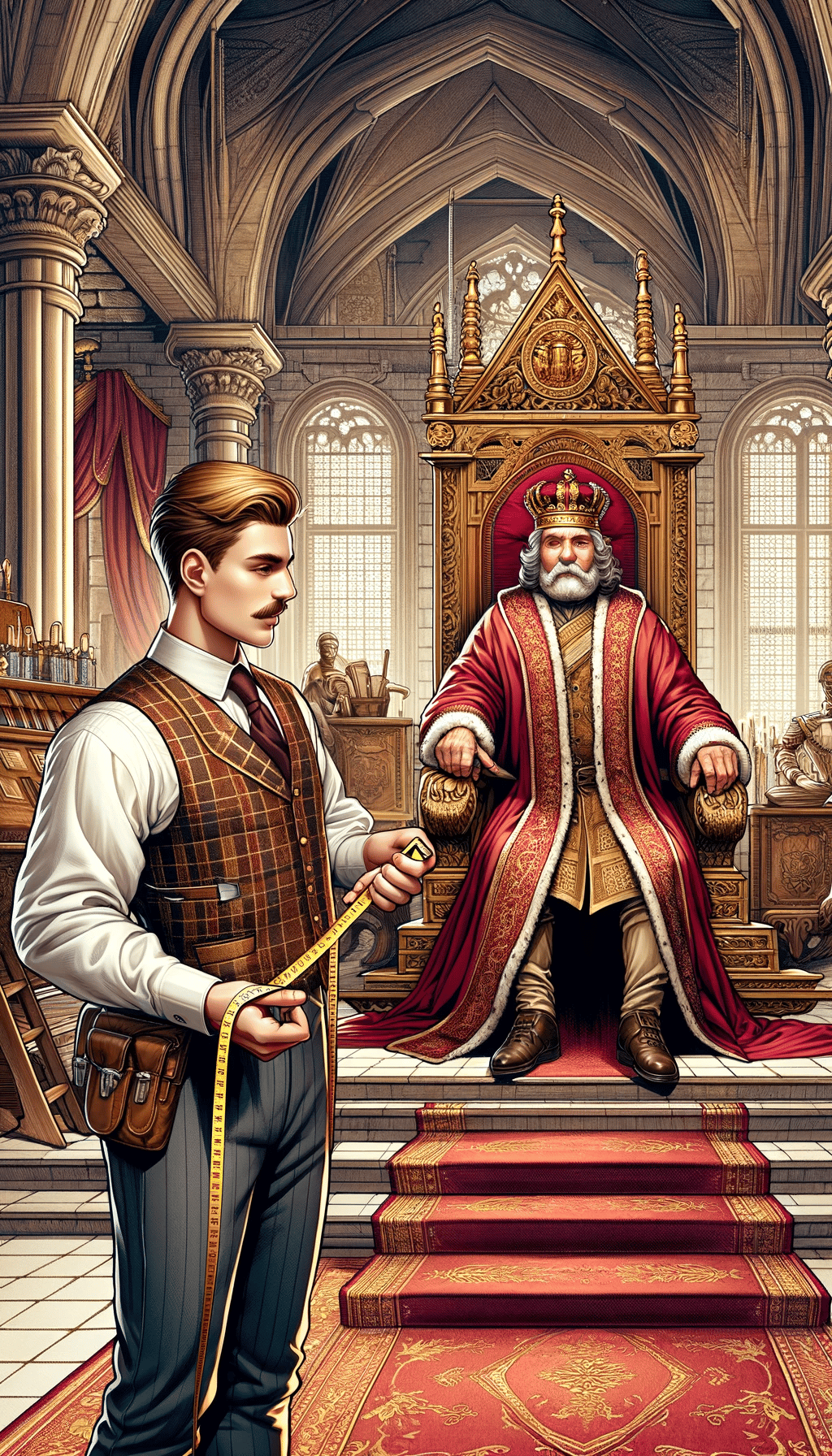

The very next day, he went to the King’s palace and mounted the steps as bold as you please.

“Hey, minnikin, manikin, who comes here?” asked the King’s warders. And when they heard who he was and what his errand was, they laughed no less than the townspeople had done.

“Have a care for thy head, little man,” they cried, but the Tailor would not listen to them. Question the King he would though he died for it, and seeing there was no other way to satisfy him, the warders brought him to the King.

The King was as cross as a King could be that morn, and no wonder, for his new velvet doublet set awry and what the trouble was he could not tell, for all he was so wise.

He was just about to abolish the making of doublets in his land when, looking up, he spied the little Tailor at his throne. And it would have gone hard with the Tailor had he not spoken speedily and to the purpose.

“I have come to ask the question, if it please Your Majesty,” he cried; and ask it he did without delay. “What am I thinking of?” said he.

“That I will have no answer for thy silly question, clown,” thundered the King; and the very look on his face made the warders tremble.

But the little Tailor was not afraid.

“Nay, nay, Your Majesty,” said he. “I was but thinking that Your Majesty’s fine doublet doth set awry because it hath more eyelets for its lacing on the one side than it hath upon the other.”

There was just one thing for the King to do then, to keep his promise, and he did it royally. The counsellors were called back, and all things were as in days gone by.

Aye, and the little Tailor was made Court Tailor in the bargain.