The Cordyce Steel Mills stood a little aside from the city of Greenfield, as if they were a little too good to associate with common factories. James Henry Cordyce sat in a huge leather chair in his private office. He was a man nearly sixty years of age whose dark brown hair was still untouched by gray. He had rather hard lines around his mouth, but softer ones around his eyes. Printed on the ground-glass top of his door were these words in black and gold:

J. H. Cordyce—President

Private

Once a year J. H. Cordyce allowed himself a holiday. If he had a weakness, it was for healthy boys—boys running without their hats, boys jumping, boys throwing rings, boys swimming, boys vaulting with a long pole. And in company with three other extremely rich men he arranged, once a year, a Field Day for the town of Intervale. The men attended it in person, and supplied all the money. This was Field Day.

All through the spring and early summer months, boys were in training for miles around, getting ready for Intervale’s Field Day. And not only boys, but men also, old and young, and girls of all ages into the bargain. Prizes were offered for tennis, baseball, rowing, swimming, running, and every imaginable type of athletic feat. But usually the interest of the day centered on a free-for-all race of one mile, which everyone enjoyed, and a great many people entered. A prize of twenty-five dollars was offered to the winner of this race, and also a silver trophy cup with little wings on its handles. Sometimes this cup was won by a middle-aged man, sometimes by a girl, and sometimes by a trained athlete. Mr. Cordyce smiled about his eyes as he closed his desk, ordered his limousine, and went out and locked the door of his office. The mill had been closed down for the day. Everyone attended Field Day.

Henry was washing the concrete drives at Dr. McAllister’s at this moment. He heard the doctor call to him from the road, so he promptly turned off the hose and ran out to see what was wanted.

“Hop in,” commanded the doctor, not stopping his engine. “You ought to go to see the stunts at the athletic meet. It’s Field Day.”

Henry did not wish to delay the doctor, so he “hopped in.”

“Can’t go myself,” said Dr. McAllister. “I’ll just drop you at the grounds. There’s no charge for admittance. You just watch all the events and report to me who wins.”

Henry tried to explain to his friend that he ought to be working, but there was actually no time. And when he found himself seated on the bleachers and the stunts began, he forgot everything in the world except the exciting events before his eyes.

Henry had no pencil, but he had an excellent memory. He repeated over and over, the name of each winner as it appeared on the huge signboard.

It was nearly eleven o’clock when the free-for-all running race was announced.

“What do they mean—free-for-all?” asked Henry of a small boy at his side.

“Why, just anybody,” explained the boy, curiously. “Didn’t you ever see one? Didn’t you see the one last year?”

“No,” said Henry.

The boy laughed. “That was a funny one,” he said. “There was a college runner in it, and a couple of fat men, and some girls—lots of people. And the little colored boy over there won it. You just ought to have seen that boy run! He went so fast you couldn’t see his legs. Beat the college runner, you know.”

Henry gazed at the winner of last year’s race. He was smaller than Henry, but apparently older. In a few minutes Henry had quietly left his place on the bleachers. When the boy turned to speak to him again, he was gone.

He had gone, in fact, to the dressing room, where boys of all sizes were putting on sandals and running trunks.

A man stepped up to him quickly.

“Want to enter?” he asked. “No time to waste.”

“Yes,” replied Henry.

The man tossed him a pair of white shoes and some blue trunks. He liked the look of Henry’s face as he paused to ask in an undertone, “Where did you train?”

“Never trained,” replied Henry.

“I suppose you know these fellows have been training all the year?” observed the man. “You don’t expect to win?”

“Oh, no!” replied Henry, apparently shocked at the idea. “But it’s lots of fun to run, you know.” He was dressed and ready by this time. How light he felt! He felt as if he could almost fly. Presently the contestants were all marshalled out to the running track. Henry was Number 4.

Now, Henry had never been trained to run, but the boy possessed an unusual quantity of common sense. “It’s a mile race,” he thought to himself, “and it’s the second half mile that counts.” So it happened that this was the main thought in his mind when the starter’s gong sounded and the racers shot away down the track. In almost no time, Henry was far behind the first half of the runners. But strangely enough, he did not seem to mind this greatly.

“It’s fun to run, anyhow,” he thought.

It was fun, certainly. He felt as if his limbs were strung together on springs. He ran easily, without effort, each step bounding into the next like an elastic.

After a few minutes of this, Henry had a new thought.

“Now you’ve tried how easy you can run, let’s see how fast you can run!”

And then not only Henry himself, but the enormous crowd as well, began to see how fast he could run. Slowly he gained on the fellow ahead of him, and passed him. With the next fellow as a goal, he gradually crept alongside, and passed him with a spurt. The crowd shouted itself hoarse. The field all along the course was black with people. Henry could hear them cheering for Number 4, as he pounded by. Six runners remained ahead of him. Here was the kind of race the crowd loved; not an easily won affair between two runners, but a gradual victory between the best runner and overpowering odds. Henry could see the finish-flag now in the distance. He began to spurt. He passed Numbers 14 and 3. He passed 25, 6, and 1 almost in a bunch. Number 16 remained ahead. Then Henry began to think of winning. How much the twenty-five dollar prize would mean to Jess and the rest! Number 16 must be passed.

“I’m going to win this race!” he said quietly in his own mind. “I’ll bet you I am!” The thought lent him speed.

“Number 4! Number 4!” yelled the crowd. Henry did not know that the fellow ahead had been ahead all the way, and just because he—Henry—had slowly gained over them all, the crowd loved him best.

Henry waited until he could have touched him. He was within three yards of the wire. He bent double, and put all his energy into the last elastic bound. He passed Number 16, and shot under the wire.

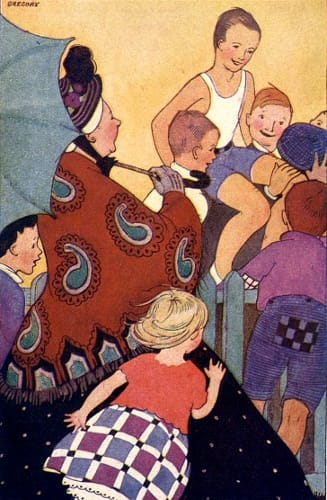

Then the crowd went wild. It scrambled over and under the fence, cheering and blowing its horns. Henry felt himself lifted on many shoulders and carried panting up to the reviewing stand. He bowed laughing at the sea of faces, and took the silver cup with its little wings in a sort of dream. It is a wonder he did not lose the envelope containing the prize, for he hardly realized when he took it what it was.

Then someone said, “What’s your name, boy?”

That called him to earth. He had to think quickly under cover of getting his breath.

“Henry James,” he replied. This was perfectly true, as far as it went. In a moment the enormous signboard flashed out the name:

HENRY JAMES No. 4. AGE 13

WINNER OF FREE-FOR-ALL

Meanwhile the man of the dressing room was busy locating Mr. Cordyce of the Cordyce Mills. He knew that was exactly the kind of story that old James Henry would like.

“Yes, sir,” he said smiling. “I says to him, ‘You don’t expect to win, of course.’ And he says to me, ‘Oh, no, but it’s lots of fun to run, you know.'”

“Thank you, sir,” returned Mr. Cordyce. “That’s a good story. Bring the youngster over here, if you don’t mind.”

When Henry appeared, a trifle shaken out of his daze and anxious only to get away, Mr. Cordyce stretched out his hand. “I like your spirit, my boy,” he said. “I like your running, too. But it’s your spirit that I like best. Don’t ever lose it.”

“Thank you,” said Henry, shaking hands. And there was only one in the whole crowd that knew who was shaking hands with whom, least of all James Henry and Henry James.