With twenty-five dollars in his hand, Henry felt like a millionaire as he edged through the crowd to the gate.

“That’s the boy,” he heard many a person say when he was forced to hold his silver cup in view out of harm’s way.

When Dr. McAllister drove into his yard he found a boy washing the concrete drives as calmly as if nothing had happened. He chuckled quietly, for he had stopped at the Fair Grounds for a few minutes himself, and held a little conversation with the score-keeper. When Henry faithfully repeated the list of winners, however, he said nothing about it.

“What are you going to do with the prize?” queried Dr. McAllister.

“Put it in the savings bank, I guess,” replied Henry.

“Have you an account?” asked his friend.

“No, but Jess says it’s high time we started one.”

“Good for Jess,” said the doctor absently. “I remember an old uncle of mine who put two hundred dollars in the savings bank and forgot all about it. He left it in there till he died, and it came to me. It amounted to sixteen hundred dollars.”

“Whew!” said Henry.

“He left it alone for over forty years, you see,” explained Dr. McAllister.

When Henry arrived at his little home in the woods with the twenty-five dollars (for he never thought of putting it in the bank before Jess saw it), he found a delicious lunch waiting for him. Jess had boiled the little vegetables in clear water, and the moment they were done she had drained off the water in a remarkable drainer, and heaped them on the biggest dish with melted butter on top.

His family almost forgot to eat while Henry recounted the details of the exciting race. And when he showed them the silver cup and the money they actually did stop eating, hungry as they were.

“I said my name was Henry James,” repeated Henry.

“That’s all right. So it is,” affirmed Jess. “It’s clever, too. You can use that name for your bank book.”

“So I can!” said Henry, delighted. “I’ll put it in the bank this very afternoon. And by the way, I brought something for dinner tonight.”

Jess looked in the bag. There were a dozen smooth, brown potatoes.

“I know how to cook those,” said Jess, nodding her head wisely. “You just wait!”

“Can’t wait, hardly,” Henry called back as he went to work.

When he had gone, Benny frolicked around noisily with the dog.

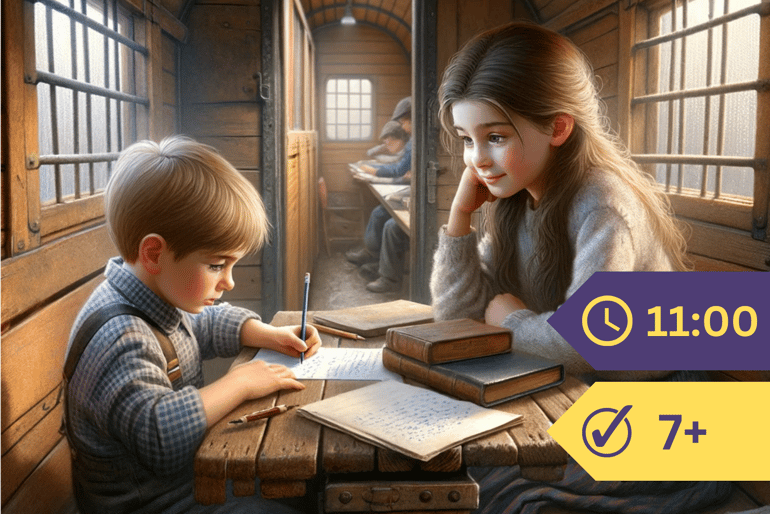

“Benny,” Jess exclaimed suddenly, as she hung her dish towels up to dry, “it’s high time you learned to read.”

“No school now,” said Benny hopefully.

“No, but I can teach you. If I only had a primer!”

“Let’s make one,” suggested Violet, shaking her hair back. “We have saved all the wrapping paper off the bundles, you know.”

Jess was staring off into space, as she always did when she had a bright idea.

“Violet,” she cried at last, “remember those chips? We could whittle out letters like type—make each letter backwards, you know.”

“And stamp them on paper!” finished Violet.

“There would be only twenty-six in all. It wouldn’t be awfully hard,” said Jess. “We wouldn’t bother with capitals.”

“What could we use for ink?” Violet wondered, wrinkling her forehead.

“Blackberry juice!” cried Jess. The two girls clapped their hands. “Won’t Henry be surprised when he finds that Benny can read?”

Now from this conversation Benny gathered that this type-business would take his sisters quite a while to prepare. So he was not much worried about his part of the work. In fact, he sorted out chips very cheerfully and watched his teachers with interest as they dug carefully around the letters with the two knives.

“We’ll teach him two words to begin with,” said Jess. “Then we won’t have to make the whole alphabet at once. Let’s begin to teach him see.”

“That’s easy,” agreed Violet. “And then we won’t have to make but two letters, s and e.”

“And the other word will be me,” cried Jess. “So only three pieces of type in all, Violet.”

Jess cut the wiggly s, because she had the better knife, while Violet struggled with the e. Then Jess cut a wonderful m while Violet sewed the primer down the back, and gathered a cupful of blackberries. As she sat by, crushing the juice from the berries with a stick, Jess planned the ink pad.

“We’ll have to use a small piece of the wash-cloth, I’m afraid,” she said at last.

But finally they were obliged to cut off only the uneven bits of cloth which hung around the edges. These they used for stuffing for the pad, and covered them with a pocket which Violet carefully ripped from her apron. When this was sewed firmly into place, and put into a small saucer, Jess poured on the purple juice. Even Benny came up on his hands and knees to watch her stamp the first s. It came out beautifully on the first page of the primer, purple and clean-cut. The e was almost as good, and as for the m, Jess’ hand shook with pure pride as she stamped it evenly on the page. At last the two words were completed. In fact, they were done long before Benny had the slightest idea his sisters were ready for him.

He came willingly enough for his first lesson, but he could not tell the two words apart.

“Don’t you see, Benny?” Jess explained patiently. “This one with the wiggly s says see?” But Benny did not “see.”

“I’ll tell you, Jess,” said Violet at last. “Let’s print each word again on a separate card. That’s the way they do at school. And then let him point to see.”

The girls did this, using squares of stiff brown paper. Then they called Benny. Very carefully, Jess explained again which word said see, hissing like a huge snake to show him how the s sounded. Then she mixed the cards and said encouragingly, “Now, Benny, point to s-s-s-ee.”

Benny did not move. He sat with his finger on his lip.

But the children were nearly petrified with astonishment to see Watch cock his head on one side and gravely put his paw on the center of the word! Now, this was only an accident. Watch did not really know one of the words from the other. But Benny thought he did. And was he going to let a dog get ahead of him? Not Benny! In less time than it takes to tell it, Benny had learned both words perfectly.

“Good old Watch,” said Jess.

“It isn’t really hard at all,” said Benny. “Is it, Watch?”

During all this experiment Jess had not forgotten her dinner. When you are living outdoors all the time you do not forget things like that. In fact both girls had learned to tell the time very accurately by the sun.

Jess started up a beautiful little fire of cones. As they turned into red-hot ashes and began to topple over one by one into the glowing pile, Jess laughed delightedly. She had already scrubbed the smooth potatoes and dried them carefully. She now poked them one by one into the glowing ashes with a stick from a birch tree. Whenever a potato lit up dangerously she gave it a poke into a new position. And when Henry found her, she was just rolling the charred balls out onto the flat stones.

“Burned ’em up?” queried Henry.

“Burned, nothing!” cried Jess energetically. “You just wait!”

“Can’t wait, hardly,” replied Henry smiling.

“You said that a long time ago,” said Benny.

“Well, isn’t it true?” demanded Henry, rolling his brother over on the pine needles.

“Come,” said Violet breathlessly, forgetting to ring the bell.

“Hold them with leaves,” directed Jess, “because they’re terribly hot. Knock them on the side and scoop them out with a spoon and put butter on top.”

The children did as the little cook requested, sprinkled on a little salt from the salt shaker, and took a taste.

“Ah!” said Henry.

“It’s good,” said Benny blissfully. It was about the most successful meal of all, in fact. When the children in later years recalled their different feasts, they always came back to the baked potatoes roasted in the ashes of the pine cones. Henry said it was because they were poked with a black-birch stick. Benny said it was because Jess nearly burned them up. Jess herself said maybe it was the remarkable salt shaker which had to stand on its head always, because there was no floor to it.

After supper the children still were not too sleepy to show Henry the new primer, and allow Benny to display his first reading lesson. Henry, greatly taken with the idea, sat up until it was almost dark, chipping out the remaining letters of the alphabet.

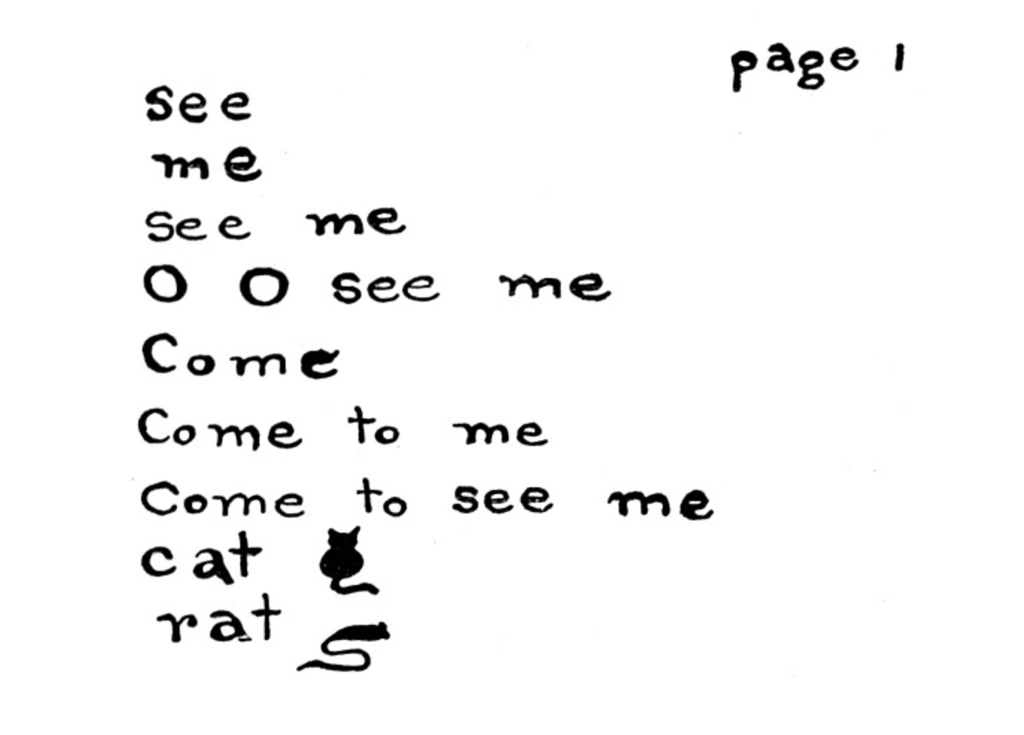

If you should ever care to see this interesting primer, which was finally ten pages in length, you might examine this faithful copy of its first page, which required four days for its completion:

Henry always insisted that the rat’s tail was too long, but Jess said his knife must have slipped when he was making the a, so they were even, after all.