Is there a nicer place in which to play than an old apple orchard? Once under those favorite trees whose branches sweep the ground, you are quite shut off from the great, troublesome, outside world. And how happy and safe you feel in that green world of your own!—a world just made for children, a world of grass and leaves and birds and flowers, where lessons and grown-up people alike have no part.

In the lightly swinging branches you find prancing horses, and on many a mad ride they carry you. The larger ones are steep paths leading up mountain sides. Great chasms yawn beneath you. Here only the daring, the cool-headed, may hope to be successful and reach the highest points without danger to their bones.

Out here the girls bring their dolls, and play house. Nothing can make a more interesting or a more surprising house than an apple tree, its rooms are so many and of such curious shapes. Then, too, the seats in these rooms are far more comfortable than the chairs used by ordinary people in everyday houses. The doings of the Robin family are overlooked by its windows. One is amazed to see how many fat worms Mother Robin manages to pop down the yawning baby throats, and wonders how baby robins ever live to grow up.

From these windows you watch the first flying lesson; and you laugh to see the little cowards cling to the branch close by, paying little heed to their parents’ noisy indignation. All the same, you wish that you too might suddenly grow a pair of wings, and join the little class, and learn to do the one thing that seems even more delightful than tree climbing.

That you children long to be out of the schoolroom this minute, out in the orchard so full of possibilities, I do not wonder a bit. But as the big people have decided that from now on for some months you must spend much of your time with lesson books, I have a plan to propose.

What do you say to trying to bring something of the outdoor places that we love into the schoolroom, which we do not love as much as we should if lessons were always taught in the right way?

Now let us pretend—and even grown-up people, who can do difficult sums, and answer questions in history and geography better than children, cannot “pretend” one half so well—now let us pretend that we are about to spend the morning in the orchard.

Here we go, out of the schoolroom into the air and sunshine, along the road, up the hill, till we reach the stone wall beyond which lies our orchard.

Ah! it is good to get into the cool of the dear, friendly trees. And just now, more than ever, they seem friendly to you boys and girls; for they are heavy with apples,—beautiful red and golden apples, that tempt you to clamber up into the green sea of leaves above.

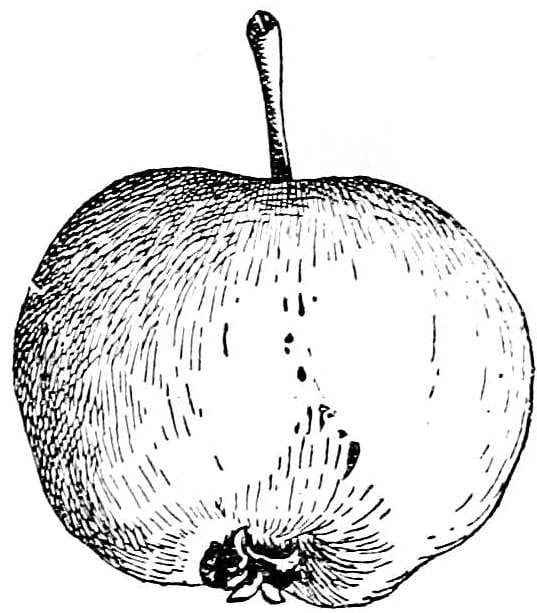

Now let us “pretend” that you have had your fill, and are ready to gather quietly about me on the long grass. But first, please, one of you bring me an apple. Let it be well-grown and rounded, with a rosy, sun-burned cheek; for, as we are to spend some little time with this apple, the more perfect it is in shape, the richer in color, the sounder all the way through, the better. It is good to be as much as possible with things that are beautiful and wholesome and hearty, even though they are only apples.

Here we have a fine specimen. What do you know, any of you, about this apple? Perhaps this seems a strange question. But when we see something that is fine and beautiful, is it strange that we wish to know its history? If I see a man or a woman who seems to me all that a man or woman should be; if he or she is fine-looking and fine-acting, straight and strong, and beautiful and kind, and brave and generous,—I ask, “Who is he? Where does she come from? What have they done?”

Of course, a fine apple is not so interesting as a fine man or woman, or as a fine boy or girl. Still there is much of interest to learn even about an apple.

None of you seems anxious to tell the apple’s story, so I shall have to start you with some questions.

Do you remember playing in this same orchard last spring?

Yes, you have not forgotten those Saturdays in May. The trees were all pink and white with apple blossoms. The air was sweet with fragrance, and full of the voices of birds, and of bees that were bustling about from flower to flower. No, indeed! you have not forgotten those happy mornings. What is more, you never will. They are among the things that will stay by you, and be a rest and help to you all your lives. I wish there were no child living that might not carry with him always the memory of May days in an apple orchard.

How has it come about, do you suppose, that these trees which in May were covered with flowers are now heavy with apples?

Can any of you children answer this riddle? How have these great apples managed to take the place of the delicate apple blossoms?

There are some children who keep their eyes open, and really see what is going on about them, instead of acting as if they were quite blind; and perhaps some such child will say, “Oh, yes! I know how it happened. I have seen it all,” and will be able to tell the whole story at once.

I should like very much to meet that boy or girl, and I should like to take a country walk with him or her; for there are so few children, or grown people either, who use both their eyes to see with, and the brain which lies back of their eyes to think and question with, that it is a rare treat to meet and to go about with one of them.

But I should be almost as much pleased to meet the child who says, “Well, I know that first the blossoms come. Early in May they make the orchard so nice to play in. But in a few days they begin to fall. Their little white leaves come dropping down like snowflakes; and soon after, if you climb out along the branches and look close, where there was a blossom before, you find now a little green thing something like a knob. This tiny knob keeps growing bigger and bigger, and then you see that it is a baby apple. As the weeks go by, the little apple grows into a big one; and at last the green begins to fade away, and the red and yellow to come. One day you find the great grown apple all ripe, and ready to eat. But I never could see just what made it come like that, such a big, heavy apple from such a little flower, and I always wondered about it.”

Now, if we wonder about the things we see, we are on the right road. The child who first “sees” what is happening around him, and then “wonders” and asks questions, is sure to be good company to other people and to himself. (And as one spends more time with himself than with any one else, he is lucky if he finds himself a pleasant companion.) Such a child has not lost the use of his eyes, as so many of us seem to have done. And when the little brain is full of questions, it bids fair to become a big brain, which may answer some day the questions the world is asking.

Before I tell you just how the big apple managed to take the place of the pretty, delicate flower, let us take a good look at this flower.

But in September apple flowers are not to be had for the asking. Not one is to be found on all these trees. So just now we must use the picture instead. And when May comes, your teacher will bring you a branch bearing the beautiful blossoms; or, better still, perhaps she will take you out into the orchard itself, and you can go over this chapter again with the lovely living flowers before you.

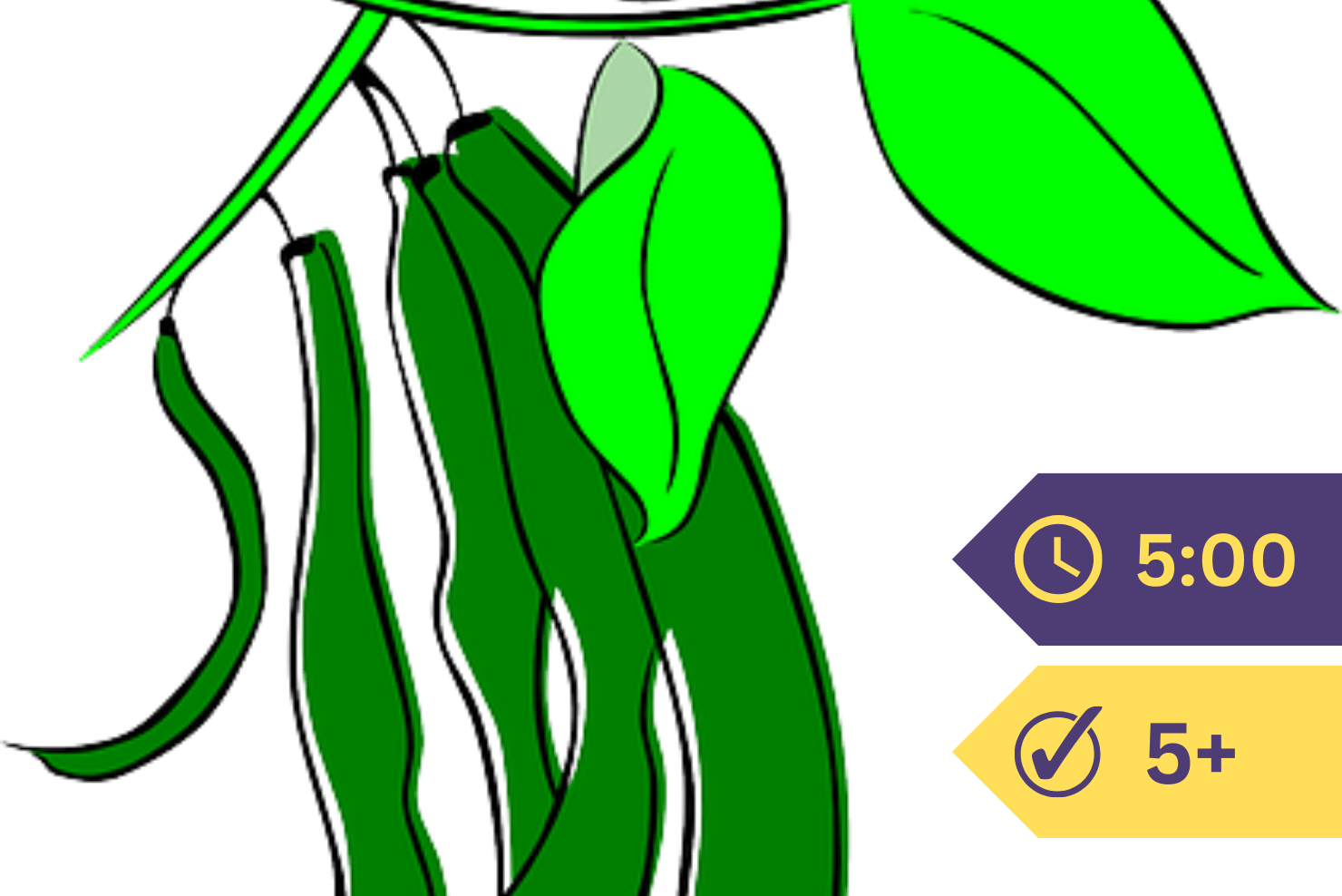

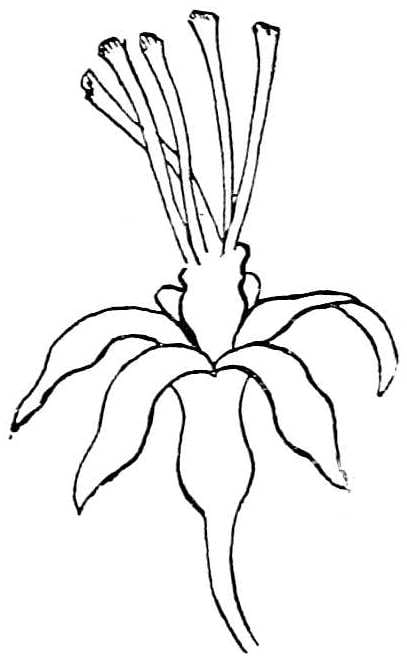

Now, as you look at this picture of the apple flower, you see a circle made up of five pretty leaves. Sometimes these are white; again they are pink. And in the center what do you see? Why, there you see a quantity of odd-looking little things whose names you do not know. They look somewhat like small, rather crooked pins; for on the tips of most of them are objects which remind you of the head of a pin.

If you were looking at a real flower, you would see that these pin heads were little boxes filled with a yellow dust which comes off upon one’s fingers; and so for the present we will call them “dust boxes.”

But besides these pins—later we shall learn their real names—besides these pins with dust boxes, we find some others which are without any such boxes. The shape of these reminds us a little of the pegs or pins we use in the game of tenpins. If we looked at them very closely, we should see that there were five of them, but that these five were joined below into one piece.

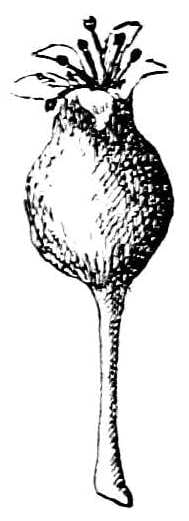

Now suppose we take the apple blossom and pull off all its pretty white flower leaves, and all the pins with dust boxes, what will be left?

This picture shows you just what is left. You see what looks like a little cup or vase. The upper part of this is cut into five pieces, which are rolled back. In the picture one of these pieces is almost out of sight. In the real blossom these pieces look like little green leaves. And set into this cup is the lower, united part of those pins which have no dust boxes on top.

I fancy that you are better acquainted with the apple blossom than ever before, never mind how many mornings you may have spent in the sweet-smelling, pink and white orchard. You know just what goes to make up each separate flower, for all the many hundreds of blossoms are made on the one plan.

And only now are you ready to hear what happened to make the apple take the place of the blossom.