Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the King’s horses

And all the King’s men

Cannot put Humpty together again.

At the very top of the hay-mow in the barn, the Speckled Hen had made her nest, and each day for twelve days she had laid in it a pretty white egg. The Speckled Hen had made her nest in this out-of-the-way place so that no one would come to disturb her, as it was her intention to sit upon the eggs until they were hatched into chickens.

Each day, as she laid her eggs, she would cackle to herself, saying, “This will in time be a beautiful chick, with soft, fluffy down all over its body and bright little eyes that will look at the world in amazement. It will be one of my children, and I shall love it dearly.”

She named each egg, as she laid it, by the name she should call it when a chick, the first one being “Cluckety-Cluck,” and the next “Cadaw-Cut,” and so on; and when she came to the twelfth egg she called it “Humpty Dumpty.”

This twelfth egg was remarkably big and white and of a very pretty shape, and as the nest was now so full she laid it quite near the edge. And then the Speckled Hen, after looking proudly at her work, went off to the barn-yard, clucking joyfully, in search of something to eat.

When she had gone, Cluckety-Cluck, who was in the middle of the nest and the oldest egg of all, called out, angrily,

“It’s getting crowded in this nest; move up there, some of you fellows!” And then he gave Cadaw-Cut, who was above him, a kick.

“I can’t move unless the others do; they’re crowding me down!” said Cadaw-Cut; and he kicked the egg next above him. And so they continued kicking one another and rolling around in the nest until one kicked Humpty Dumpty, and as he lay on the edge of the nest he was kicked out and rolled down the hay-mow until he came to a stop near the very bottom.

Humpty did not like this very well, but he was a bright egg for one so young, and after he had recovered from his shaking up he began to look about to see where he was. The barn door was open, and he caught a glimpse of trees and hedges, and green grass with a silvery brook running through it. And he saw the waving grain and the tasselled maize and the sunshine flooding it all.

The scene was very enticing to the young egg, and Humpty at once resolved to see something of this great world before going back to the nest.

He began to make his way carefully through the hay, and was getting along fairly well when he heard a voice say,

“Where are you going?”

Humpty looked around and found he was beside a pretty little nest in which was one brown egg.

“Did you speak?” he asked.

“Yes,” replied the brown egg; “I asked where you were going.”

“Who are you?” enquired Humpty; “do you belong in our nest?”

“Oh, no!” answered the brown egg; “my name is Coutchie-Coulou, and the Black Bantam laid me about an hour ago.”

“Oh,” said Humpty, proudly; “I belong to the Speckled Hen, myself.”

“Do you, indeed!” returned Coutchie-Coulou. “I saw her go by a little while ago, and she’s much bigger than the Black Bantam.”

“Yes, and I’m much bigger than you,” replied Humpty. “But I’m going out to see the world, and if you like to go with me I’ll take good care of you.”

“Isn’t it dangerous for eggs to go about all by themselves?” asked Coutchie, timidly.

“Perhaps so,” answered Humpty; “but it’s dangerous in the nest, too; my brothers might have smashed me with their kicking. However, if we are careful we can’t come to much harm; so come along, little one, and I’ll look after you.”

Coutchie-Coulou gave him her hand while he helped her out of the nest, and together they crept over the hay until they came to the barn floor. They made for the door at once, holding each other tightly by the hand, and soon came to the threshold, which appeared very high to them.

“We must jump,” said Humpty.

“I’m afraid!” cried Coutchie-Coulou. “And I declare! there’s my mother’s voice clucking, and she’s coming this way.”

“Then hurry!” said Humpty. “And do not tremble so or you will get yourself all mixed up; it doesn’t improve eggs to shake them. We will jump, but take care not to bump against me or you may break my shell. Now,—one,—two,—three!”

They held each other’s hand and jumped, alighting safely in the roadway. Then, fearing their mothers would see them, Humpty ran as fast as he could go until he and Coutchie were concealed beneath a rose-bush in the garden.

“I’m afraid we’re bad eggs,” gasped Coutchie, who was somewhat out of breath.

“Oh, not at all,” replied Humpty; “we were laid only this morning, so we are quite fresh. But now, since we are in the world, we must start out in search of adventure. Here is a roadway beside us which will lead us somewhere or other; so come along, Coutchie-Coulou, and do not be afraid.”

The brown egg meekly gave him her hand, and together they trotted along the roadway until they came to a high stone wall, which had sharp spikes upon its top. It seemed to extend for a great distance, and the eggs stopped and looked at it curiously.

“I’d like to see what is behind that wall,” said Humpty, “but I don’t think we shall be able to climb over it.”

“No, indeed,” answered the brown egg, “but just before us I see a little hole in the wall, near the ground; perhaps we can crawl through that.”

They ran to the hole and found it was just large enough to admit them. So they squeezed through very carefully, in order not to break themselves, and soon came to the other side.

They were now in a most beautiful garden, with trees and bright-hued flowers in abundance and pretty fountains that shot their merry sprays far into the air. In the center of the garden was a great palace, with bright golden turrets and domes, and many windows that glistened in the sunshine like the sparkle of diamonds.

Richly dressed courtiers and charming ladies strolled through the walks, and before the palace door were a dozen prancing horses, gaily caparisoned, awaiting their riders.

It was a scene brilliant enough to fascinate anyone, and the two eggs stood spellbound while their eyes feasted upon the unusual sight.

“See!” whispered Coutchie-Coulou, “there are some birds swimming in the water yonder. Let us go and look at them, for we also may be birds some day.”

“True,” answered Humpty, “but we are just as likely to be omelets or angel’s-food. Still, we will have a look at the birds.”

So they started to cross the drive on their way to the pond, never noticing that the King and his courtiers had issued from the palace and were now coming down the drive riding upon their prancing steeds. Just as the eggs were in the middle of the drive the horses dashed by, and Humpty, greatly alarmed, ran as fast as he could for the grass.

Then he stopped and looked around, and behold! there was poor Coutchie-Coulou crushed into a shapeless mass by the hoof of one of the horses, and her golden heart was spreading itself slowly over the white gravel of the driveway!

Humpty sat down upon the grass and wept grievously, for the death of his companion was a great blow to him. And while he sobbed, a voice said to him,

“What is the matter, little egg?”

Humpty looked up, and saw a beautiful girl bending over him.

“One of the horses has stepped upon Coutchie-Coulou,” he said; “and now she is dead, and I have no friend in all the world.”

The girl laughed.

“Do not grieve,” she said, “for eggs are but short-lived creatures at best, and Coutchie-Coulou has at least died an honorable death and saved herself from being fried in a pan or boiled in her own shell. So cheer up, little egg, and I will be your friend—at least so long as you remain fresh. A stale egg I never could abide.”

“I was laid only this morning,” said Humpty, drying his tears, “so you need have no fear. But do not call me ‘little egg,’ for I am quite large, as eggs go, and I have a name of my own.”

“What is your name?” asked the Princess.

“It is Humpty Dumpty,” he answered, proudly. “And now, if you will really be my friend, pray show me about the grounds, and through the palace; and take care I am not crushed.”

So the Princess took Humpty in her arms and walked with him all through the grounds, letting him see the fountains and the golden fish that swam in their waters, the beds of lilies and roses, and the pools where the swans floated. Then she took him into the palace, and showed him all the gorgeous rooms, including the King’s own bedchamber and the room where stood the great ivory throne.

Humpty sighed with pleasure.

“After this,” he said, “I am content to accept any fate that may befall me, for surely no egg before me ever saw so many beautiful sights.”

“That is true,” answered the Princess; “but now I have one more sight to show you which will be grander than all the others; for the King will be riding home shortly with all his horses and men at his back, and I will take you to the gates and let you see them pass by.”

“Thank you,” said Humpty.

So she carried him to the gates, and while they awaited the coming of the King the egg said,

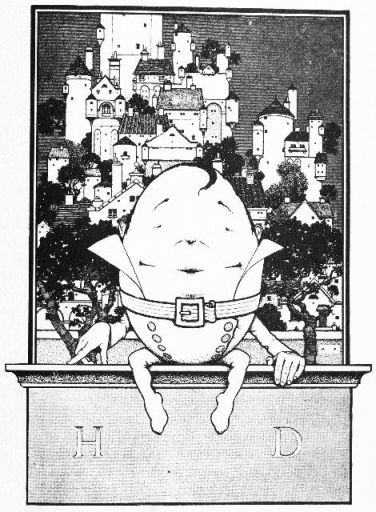

“Put me upon the wall, Princess, for then I shall be able to see much better than in your arms.”

“That is a good idea,” she answered; “but you must be careful not to fall.”

Then she sat the egg gently upon the top of the stone wall, where there was a little hollow; and Humpty was delighted, for from his elevated perch he could see much better than the Princess herself.

“Here they come!” he cried; and, sure enough, the King came riding along the road with many courtiers and soldiers and vassals following in his wake, all mounted upon the finest horses the kingdom could afford.

As they came to the gate and entered at a brisk trot, Humpty, forgetting his dangerous position, leaned eagerly over to look at them. The next instant the Princess heard a sharp crash at her side, and, looking downward, perceived poor Humpty Dumpty, who lay crushed and mangled among the sharp stones where he had fallen!

The Princess sighed, for she had taken quite a fancy to the egg; but she knew it was impossible to gather it up again or mend the matter in any way, and therefore she returned thoughtfully to the palace.

Now it happened that upon this evening several young men of the kingdom, who were all of high rank, had determined to ask the King for the hand of the Princess; so they assembled in the throne room and demanded that the King choose which of them was most worthy to marry his daughter.

The King was in a quandary, for all the suitors were wealthy and powerful, and he feared that all but the one chosen would become his enemies. Therefore he thought long upon the matter, and at last said,

“Where all are worthy it is difficult to decide which most deserves the hand of the Princess. Therefore I propose to test your wit. The one who shall ask me a riddle I cannot guess, can marry my daughter.”

At this the young men looked thoughtful, and began to devise riddles that his Majesty should be unable to guess. But the King was a shrewd monarch, and each one of the riddles presented to him he guessed with ease.

Now there was one amongst the suitors whom the Princess herself favored, as was but natural. He was a slender, fair-haired youth, with dreamy blue eyes and a rosy complexion, and although he loved the Princess dearly he despaired of finding a riddle that the King could not guess.

But while he stood leaning against the wall the Princess approached him and whispered in his ear a riddle she had just thought of. Instantly his face brightened, and when the King called, “Now, Master Gracington, it is your turn,” he advanced boldly to the throne.

“Speak your riddle, sir,” said the King, gaily; for he thought this youth would also fail, and that he might therefore keep the Princess by his side for a time longer.

But Master Gracington, with downcast eyes, knelt before the throne and spoke in this wise:

“This is my riddle, oh, King:

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the King’s horses

And all the King’s men

Cannot put Humpty together again!”

“Read me that, sire, an’ you will!”

The King thought earnestly for a long time, and he slapped his head and rubbed his ears and walked the floor in great strides; but guess the riddle he could not.

“You are a humbug, sir!” he cried out at last; “there is no answer to such a riddle.”

“You are wrong, sire,” answered the young man; “Humpty Dumpty was an egg.”

“Why did I not think of that before!” exclaimed the King; but he gave the Princess to the young man to be his bride, and they lived happily together.

And thus did Humpty Dumpty, even in his death, repay the kindness of the fair girl who had shown him such sights as an egg seldom sees.