Once upon a time, there were only Native Americans upon the earth, and the tribes had a Great Spirit who was their ruler. He had a little daughter, the Wind-Child.

It was thought that the Great Spirit and his daughter lived in the largest wigwam of the world. It was a mountain that stood, tall and pointed, on the edge of the sea. The winds raged about the sea coast, and no one seemed to have any power over them except the Wind-Child. They would sometimes obey her, if she came out of her father’s wigwam, the mountain, and begged them to be still.

No wonder the winds obeyed the Wind-Child. Her eyes were as bright as the stars when the west wind blew the clouds away from the sky at night. She was as fleet and strong as the north wind. She could sing as sweetly as did the south wind. And her hair was as long and soft as the mists that the east wind carried.

The Wind-Child had only one fault. She was very curious about matters which did not concern her.

One day, when the winter was almost over, there was a gale at sea. The surf rolled up and beat against the Great Spirit’s mountain. The wind was so strong that the mountain shook. It seemed as if it would topple over. The Great Spirit spoke to his daughter.

“Go out to the lodge of the cave, at the base of the mountain,” he said, “and reach out your arm and ask the wind to cease. But do not go beyond the cave, for the storm rages and it is not safe for you to go any farther.”

So the Wind-Child did as her father had asked her. She stood at the edge of the cave. She stretched out her arm and the wind quieted. Then the Wind-Child forgot to obey her father. The sun came out, and she saw many bright shells lying on the sand. The waves had washed them up during the storm. She left the mountain, and ran along the beach gathering shells.

As soon as the Wind-Child had picked up one shell, she dropped it to go on farther in search of one that was larger. On and on she went, always looking for a shell that was brighter. She suddenly found that she had gone a long way from home. She could not see the wigwam. She found herself, where the magic trail of the shells had led her, in a deep, dark forest. It was a frightful place, and the trees shut the Wind-Child in on all sides.

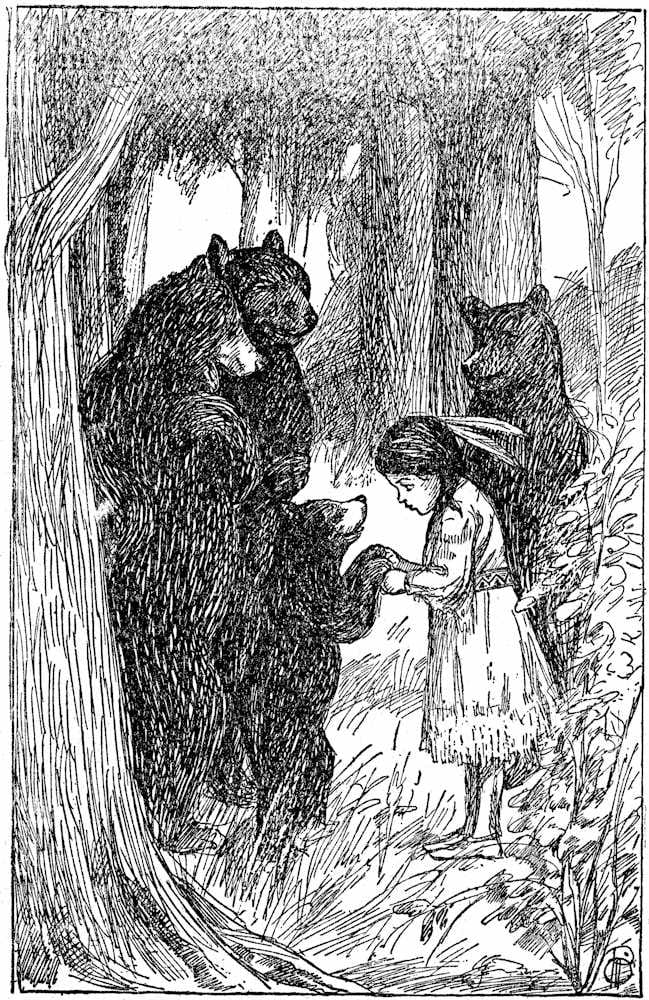

The forest was settled by a strange race of grizzly people. They were dark, rough in their ways, and wore shaggy fur clothing. Their wigwams were made of the trunks of trees. They had great fires in the open places of the woods about which they sat. They seemed glad to see the Wind-Child. The mothers crowded around her, and the children brought her nuts. They gave her a fur cloak and one of the best wigwams in which to live. When the Wind-Child begged to go home to her father, these grizzly people of the forest gave her sweets to eat. They let her taste of the thick, sweet maple syrup that they cooked in their kettles. They gave her wild honey that the bees had left the season before in the hollow trees. After eating these, the Wind-Child forgot all about her home, and lived with and learned the ways of these forest people. Years and years passed and she was still among them, grown as wild and savage as they themselves were.

The Great Spirit looked for his daughter season after season all over the earth, and still he could not find her. His mountain was deserted. His voice could be heard calling her in every wind that blew. Great drought and famine came upon the land because he neglected the earth. It was a time of great suffering. But one day he came upon the grizzly people. They were moving their camp from one part of the forest to another. In their midst was the Wind-Child, looking almost like one of them. She knew her father, though, and ran to him, begging to go home with him. He took her in his arms, but he turned in anger toward her captors.

As the Great Spirit gazed in anger upon the grizzly people they drew their fur cloaks over their heads. They dropped down to the ground at his feet to beg for mercy. The Great Spirit left the forest. As he did so these wild people of the woods found that they could not rise to their feet again. They were not able to draw their fur cloaks from their heads. They went about on all fours, covered from head to foot with shaggy fur. They could not speak, but could only growl.

They were the first bears, and there have been bears ever since in place of the strange savages who captured the Wind-Child.

The Great Spirit took the Wind-Child to the top of the mountain and they lived there always. On her return the rain fell and the sun shone, and there was plenty in the earth again. But the bear tribe prowled the earth, hunted by the Indians, because of the Wind-Child’s curiosity.