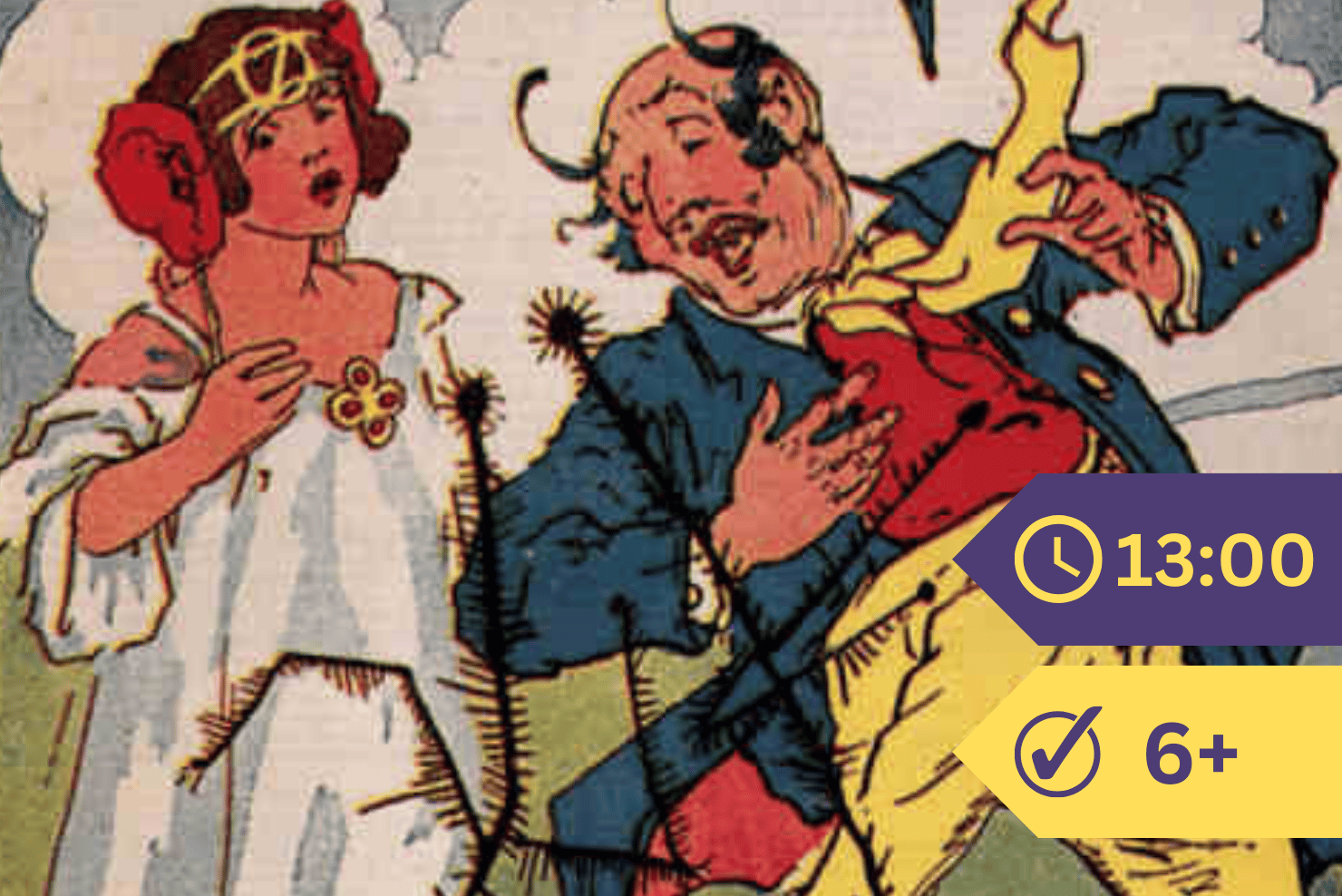

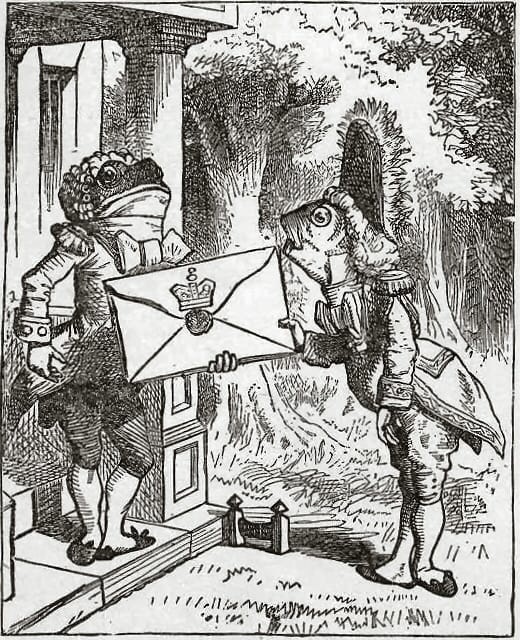

For a while Alice stood and looked at the house and tried to think what to do next, when a footman ran out of the wood (from the way he was dressed, she took him to be a footman; though if she had judged by his face she would have called him a fish) and knocked at the door with his fist. A footman with a round face and large eyes, came to the door. Alice wanted to know what it all meant, so she crept a short way out of the wood to hear what they said.

The Fish Footman took from under his arm a great letter and handed it to the other and said in a grave tone “For the Duchess; from the Queen.” The Frog Footman said in the same grave tone, “From the Queen, for the Duchess.” Then they both bowed so low that their heads touched each other.

All this made Alice laugh so much that she had to run back to the wood for fear they would hear her, and when she next peeped out the Fish Footman was gone, and the other sat on the ground near the door and stared up at the sky.

Alice went up to the door and knocked.

“There’s no sort of use for you to knock,” said the Footman, “I’m on the same side of the door that you are, and there is so much noise in the room that no one could hear you.” There was, indeed, a great noise in the house—a howling and sneezing, with now and then a great crash, as if a dish or a pot had been broken to pieces.

“Please, then,” said Alice, “how am I to get in?”

“There might be some sense in your knocking,” the Footman went on, “if we were not both on the same side of the door. If you were in the room, you might knock and I could let you out, you know.” He looked up at the sky all the time he was speaking, which Alice thought was quite rude. “But perhaps he can’t help it,” she thought, “his eyes are so near the top of his head. Still he might tell me what I ask him—How am I to get in?” she asked.

“I shall sit here,” the Footman said, “till tomorrow—”

Just then the door of the house flew open and a large plate skimmed out straight at his head; it just grazed his nose and broke on one of the trees near him. “—or next day, maybe,” he went on in the same tone as if he had not seen the plate.

“How am I to get in?” Alice asked as loud as she could speak.

“Are you to get in at all?” he said. “That’s the first thing, you know.”

It was, no doubt; but Alice didn’t like to be told so.

The Footman seemed to think this a good time to say again, “I shall sit here on and off, for days and days.”

“But what am I to do?” said Alice.

“Do what you like,” he said.

“Oh, there’s no use to try to talk to him,” said Alice; “he has no sense at all.” And she opened the door and went in.

The door led right into a large room that was full of smoke from end to end: the Duchess sat on a stool and held a child in her arms; the cook stood near the fire and stirred a large pot which seemed to be full of soup.

“There’s too much pepper in that soup!” Alice said to her-self as well as she could for sneezing. There was too much of it in the air, for the Duchess sneezed now and then; and as for the child, it sneezed and howled all the time.

A large cat sat on the hearth grinning from ear to ear.

“Please, would you tell me,” said Alice, not quite sure that it was right for her to speak first, “why your cat grins like that?”

“It’s a Cheshire cat,” said the Duchess, “and that’s why. Pig!”

She said the last word so loud that Alice jumped; but she soon saw that the Duchess spoke to the child and not to her, so she went on: “I didn’t know that Cheshire cats grinned; in fact, I didn’t know that cats could grin.”

“They all can,” said the Duchess; “and most of ’em do.”

“I don’t know of any that do,” Alice said, quite pleased to have some one to talk with.

“You don’t know much,” said the Duchess; “and that’s a fact.”

Alice did not at all like the tone in which this was said, and thought it would be as well to speak of something else. While she tried to think of what to say, the cook took the pot from the fire, and at once set to work throwing things at the Duchess and the child—the tongs came first, then pots, pans, plates and cups flew thick and fast through the air. The Duchess did not seem to see them, even when they hit her; and the child had howled so loud all the while, that one could not tell if the blows hurt it or not.

“Oh, please mind what you do!” cried Alice, as she jumped up and down in great fear, lest she should be struck.

“Hold your tongue,” said the Duchess; then she began a sort of song to the child, giving it a hard shake at the end of each line.

At the end of the song she threw the child at Alice and said, “Here, you may nurse it a bit if you like; I must go and get ready to play croquet with the Queen,” and she left the room in great haste. The cook threw a pan after her as she went, but it just missed her.

Alice caught the child, which held out its arms and legs on all sides, “just like a starfish,” Alice thought. The poor thing snorted like a steam engine when she caught it, and turned about so much, it was as much as she could do at first to hold it.

As soon as she found out the right way to nurse it, (which was to twist it up in a sort of knot, then keep tight hold of its right ear and left foot), she took it out in the fresh air. “If I don’t take this child with me,” thought Alice, “they’re sure to kill it in a day or two; wouldn’t it be wrong to leave it here?” She said the last words out loud, and the child grunted (it had left off sneezing by this time). “Don’t grunt,” said Alice, “that is not at all the right way to do.”

The child grunted again and Alice looked at its face to see what was wrong with it. There could be no doubt that it had a turn-up nose, much more like a snout than a child’s nose. Its eyes were quite small too; in fact she did not like the look of the thing at all.

“Perhaps that was not a grunt, but a sob,” and she looked to see if there were tears in its eyes.

No, there were no tears. “If you’re going to turn into a pig, my dear,” said Alice, “I’ll have no more to do with you. Mind now!” The poor thing sobbed once more (or grunted, Alice couldn’t say which).

“Now, what am I to do with this thing when I get it home?” thought Alice. Just then it grunted so loud that she looked down at its face with some fear. This time there could be no doubt about it—it was a pig!

So she set it down, and felt glad to see it trot off into the wood.

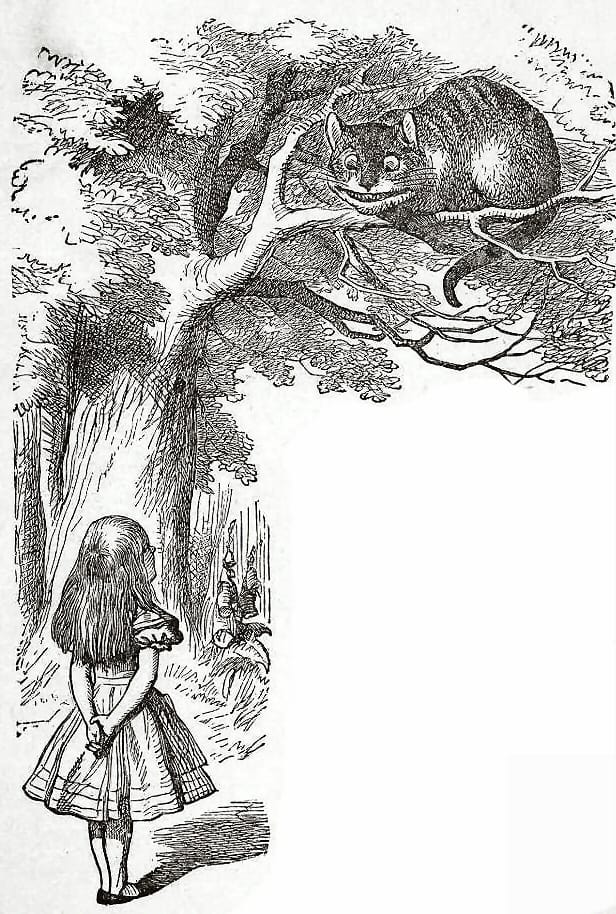

As she turned to walk on, she saw the Cheshire Cat on the bough of a tree a few yards off. The Cat grinned when it saw Alice. It looked like a good cat, she thought; still it had long claws and large teeth, so she felt she ought to be kind to it.

“Puss,” said Alice, “would you please tell me which way I ought to walk from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to go to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then you need not care which way you walk,” said the Cat.

“—so long as I get somewhere,” Alice added.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that if you don’t stop,” said the Cat.

Alice knew that this was true, so she asked: “What sort of people live near here?”

“In that way,” said the Cat, with a wave of its right paw, “lives a Hatter; and in that way,” with a wave of its left paw, “lives a March Hare. Go to see the one you like; they’re both mad.”

“But I don’t want to go where mad folks live,” said Al-ice.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat, “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad!” asked Al-ice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

Alice didn’t think that proved it at all, but she went on; “and how do you know that you are mad?”

“First,” said the Cat, “a dog’s not mad. You grant that?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then,” the Cat went on, “you know a dog growls when it’s angry, and wags its tail when it’s pleased. Now I growl when I’m pleased, and wag my tail when I’m angry. So you see, I’m mad.”

“I say the cat purrs; I do not call it a growl,” said Al-ce.

“Call it what you like,” said the Cat. “Do you play croquet with the Queen today?”

“I should like it, but I haven’t been asked yet,” said Alice.

“You’ll see me there,” said the Cat, then faded out of sight.

Alice did not think this so queer as she was now used to strange things. While she still looked at the place where it had been, it came back again, all at once.

“By-the-by, what became of the child?” it asked.

“It turned into a pig,” Alice said.

“I thought it would,” said the Cat, then once more faded out of sight.

Alice waited a while to see if it would come back, then walked on in the way in which the March Hare was said to live.

“I’ve seen Hatters,” she said to herself; “so I’ll go to see the March Hare.” As she said this, she looked up, and there sat the Cat on a branch of a tree.

“Did you say pig, or fig?” asked the Cat.

“I said pig; and I wish you wouldn’t come and go, all at once, like you do; you make one quite giddy.”

“All right,” said the Cat; and this time it faded out in such a way that its tail went first, and the last thing Alice saw was the grin which stayed some time after the rest of it had gone.

“Well, I’ve seen a cat without a grin,” thought Alice; “but a grin without a cat! It’s the strangest thing I ever saw in all my life!”

She soon came in sight of the house of the March Hare; she thought it must be the right place, as the chimneys were shaped like ears, and the roof was thatched with fur. It was so large a house, that she did not like to go too near while she was so small; so she ate a small piece from the lefthand bit of mushroom, and raised herself to 60 centimeters high. Then she walked up to the house, though with some fear lest it should be mad as the Cat had said.