I want you children to do a little gardening in the schoolroom. You will enjoy this, I am sure.

When I was a child, I took great delight in the experiments that I am going to suggest to you; and now that I am grown up, I find they please me even more than they did years ago.

During the past week I have been doing this sort of gardening; and I have become so interested in the plant babies which I have helped into the world, that I have not been at all ready to stop playing with them, even for the sake of sitting down to tell you about them.

To start my garden, I had first to get some seeds. So I put on my hat and went down to the little shop in the village, half of which is given up to tailor work, while the other half is devoted to flower raising. The gray-bearded florist tailor who runs this queer little place was greatly interested when he heard that I wanted the seeds so that I might tell you children something of their strange ways.

“Seeds air mighty interestin’ things,” he said. “Be you young or be you old, there’s nothin’ sets you thinkin’ like a seed.”

Perhaps the florist tailor had been fortunate in his friends; for I have known both grown-up people and children who year after year could see the wonder of seed and baby plant, of flower and fruit, without once stopping to say, “What brings about these changes?”

To “set thinking” some people would take an earthquake or an avalanche; but when this sort of thing is needed to start their brains working, the “thinking” is not likely to be good for much.

But I hope that some of you will find plenty to think about in the seeds which your teacher is going to show you; and I hope that these thoughts may be the beginning of an interest and curiosity that will last as long as you live.

The seeds which I got that morning were those of the bean, squash, pea, and corn; and your teacher has been good enough to get for you these same seeds, and she will show you how to do with them just what I have been doing this past week.

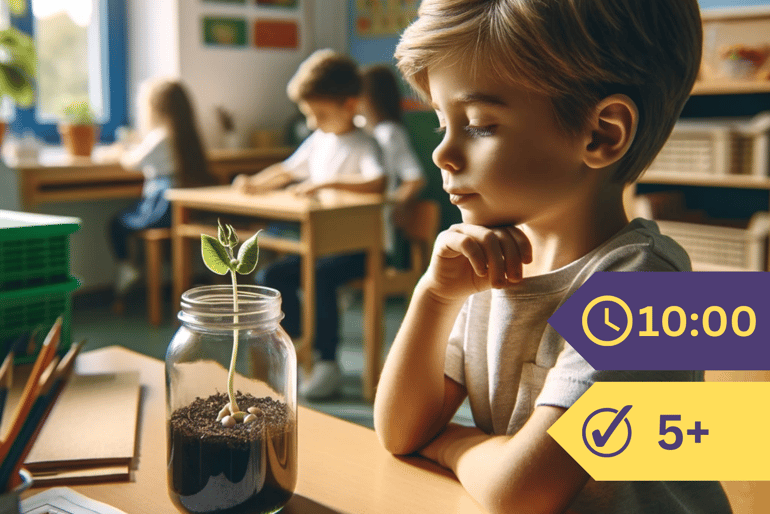

First, I filled a pot with finely sifted earth, and planted the different seeds; then I filled a glass with water, floated some cotton wool upon its surface, and in this wool laid some beans; and then my garden planting was done.

During the following days I kept the earth in the pot slightly moist. The cotton wool in the glass of water did this for itself.

And how carefully I watched my two little gardens!

For three days the pot of earth kept its secret. Nothing happened there, so far as I could see. But the beans that were laid upon the cotton wool grew fat and big by the second day, just like those that your teacher soaked over night; and by the third day their seed coats had ripped open a little way, just as your coat would rip open if it were tightly buttoned up and suddenly you grew very fat; and out of the rip in the seed coat peeped a tiny white thing, looking like the bill of a chick that is pecking its way out of the eggshell which has become too small to hold it.

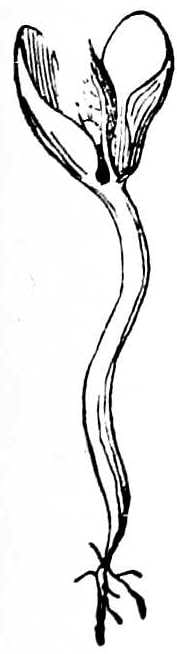

Very quickly this little white tip grew longer. It curved over and bent downward, piercing its way through the cotton wool into the water.

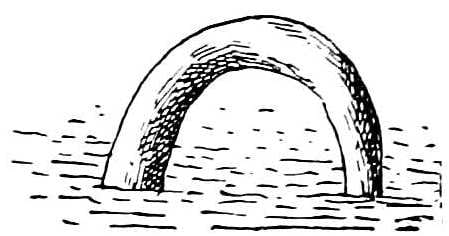

About this time the pot garden began to show signs of a disturbance. Here and there I saw what looked like the top of a thick green hoop.

What had happened, do you think?

Why, first this bean had sucked in from the damp earth so much water that it had grown too fat and big for the seed coat; and it had torn this open, just like the other bean, pushing out its little white tip; and this tip had bent down into the earth and taken a good hold there, lengthening into a real root, and sending out little root hairs that fastened it down still more firmly.

But it was not satisfied to do all its growing below. Its upper part now straightened itself out, and started right up into the air. From a hoop it turned into a stem which lifted the bean clear above the earth.

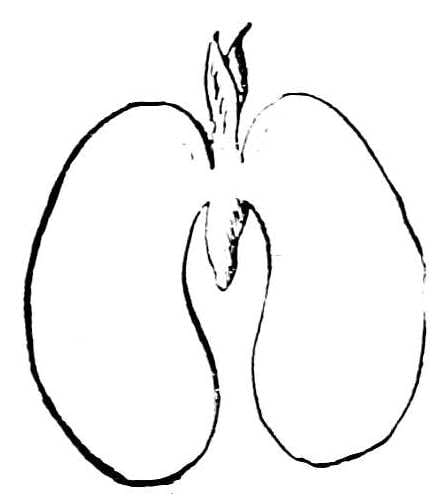

This bean was no longer the round object we usually call by that name; for its two halves had opened and spread outward, and from between these two halves grew a pair of young leaves.

As these leaves grew larger, the two half-beans began to shrink, growing smaller and more withered all the time.

Why was this, do you suppose?

To make clear the reason of this, to show just why the two halves of the bean grew smaller as the rest of the young bean plant grew larger, I must go back a way.

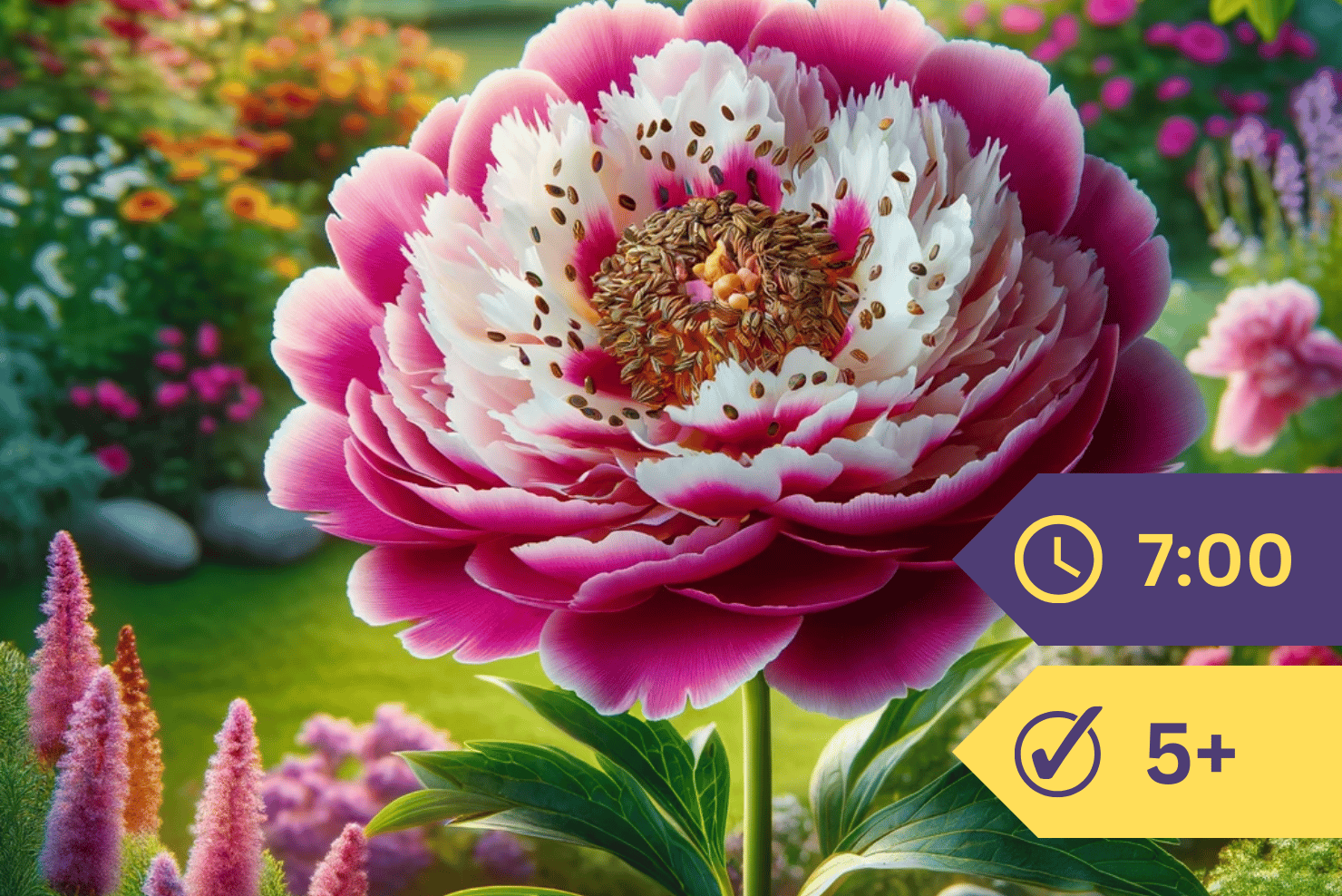

Turn to the picture of the peony seed. There you can see how the baby plant is packed away in the midst of a quantity of baby food. And in the picture of the morning-glory seed you see the same thing.

You remember that day by day the baby plant ate more and more of this food, and kept growing stronger and bigger, and that all this time the store of food kept growing smaller and smaller.

Now, if you cut open the bean, you do not see a tiny plant set in the midst of a store of food.

Why is this? This is because the baby bean plant keeps its food in its own leaves.

The seed coat of the bean is filled by these leaves, for each half of the bean is really a seed leaf. In these two thick leaves is stored all the food that is necessary to the life of the baby plant; and because of all this food which they hold, the bean plant is able to get a better start in life than many other young plants.

If you soak and strip off its seed coat, and pull apart the two thick leaves, you will find a tiny pair of new leaves already started; but you will see nothing of the sort in the seed of the morning-glory, for the reason that this is not so well stored with baby food as to be able to do more than get its seed leaves well under way.

The pea, like the bean, is so full of food, that it also is able to take care of a second pair of leaves.

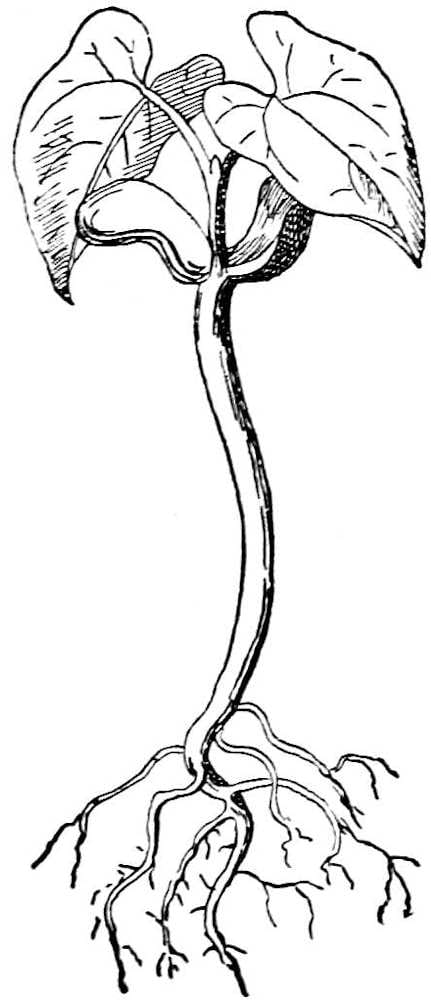

But now to go back to the young bean plant in the schoolroom garden. We were wondering why the two halves of the bean, which are really the first pair of leaves, kept growing thinner and smaller as the second pair grew larger.

Perhaps you guess now the reason for this. These first leaves, called the seed leaves, feed all the rest of the young bean plant.

Of course, as they keep on doing this, they must themselves shrink away; but they do not cease with their work till the plant is able to take care of itself.

By this time, however, the seed leaves have nothing left to live upon. They die of starvation, and soon fade and disappear.

So now you understand just what has happened to the leaves that once were so fat and large.

And I hope you will remember the difference between the seed of the morning-glory and that of the bean,—how the morning-glory packs the baby food inside the seed, of course, but outside the baby plant; while the bean packs it inside the two seed leaves, which are so thick that there is no room for anything else within the seed coat.

But really, to understand all that I have been telling you, you must see it for yourselves; you must hold in your hands the dried bean; you must examine it, and make sure that its seed shell is filled entirely by the baby plant; you must see it grow plump and big from the water which it has been drinking; you must watch with sharp eyes for that first little rip in the seed coat, and for the putting-out of the tiny tip, which grows later into stem and root; you must notice how the bent stem straightens out, and lifts the thick seed leaves up into the air; and you must observe how that other pair of leaves, which grows from between the seed leaves, becomes larger and larger as the seed leaves grow smaller and thinner, and how, when the little plant is able to hold its own in the world, the seed leaves die away.

And if day by day you follow this young life, with the real wish to discover its secret, you will begin to understand what the wise old florist tailor meant when he said,—

“Be you young or be you old, there’s nothin’ sets you thinkin’ like a seed.”