The roosters crowed and the hens clucked; the farmer’s wife began to get breakfast, and the four children slept on. Dinner time came and went, and still they slept, for it must be remembered that they had been awake and walking during the whole night. In fact, it was nearly seven o’clock in the evening when they awoke. Luckily, all the others awoke before Benny.

“Can you hear me, Jess?” said Henry, speaking very low through the wall of hay.

“Yes,” answered Jess softly. “Let’s make one big room of our nests.”

No sooner said than done. The boy and girl worked quickly and quietly until they could see each other. They pressed the hay back firmly until they had made their way into Violet’s little room. And then she in turn groped until she found Benny.

“Hello, little Cinnamon!” whispered Violet playfully.

And Benny at once made up his mind to laugh instead of cry. But laughing out loud was almost as bad, so Henry took his little brother on the hay beside him and talked to him seriously.

“You’re old enough now, Benny, to understand what I say to you. Now, listen! When I tell you to keep still after this, that means you’re to stop crying if you’re crying, or stop laughing if you’re laughing, and be just as still as you possibly can. If you don’t mind, you will be in danger. Do you understand?”

“Don’t I have to mind Jess and Violet too?” asked Benny.

“Absolutely!” said Henry. “You have to mind us all, every one of us!”

Benny thought a minute. “Can’t I ask for what I want any more?” he said.

“Indeed you can!” cried Jess and Henry together. “What is it you want?”

“I’m awful hungry,” said Benny anxiously.

Henry’s brow cleared. “Good old Benny,” he said. “We’re just going to have supper—or is it breakfast?”

Jess drew out the fragrant loaf of bread. She cut it with Henry’s jackknife into four quarters, and she and Henry took the two crusty ends themselves.

“That’s because we have to be the strongest, and crusts make you strong,” explained Jess.

Violet looked at her older sister. She thought she knew why Jess took the crust, but she did not speak.

“We will stay here till dark, and then we’ll go on with our journey,” said Henry cheerfully.

“I want a drink,” announced Benny.

“A drink you shall have,” Henry promised, “but you’ll have to wait till it’s really dark. If we should creep out to the brook now, and any one saw us—” He did not finish his sentence, but Benny realized that he must wait.

He was much refreshed from his long sleep, and felt very lively. Violet had all she could do to keep him amused, even with Cinnamon Bear and his five brothers.

At last Henry peeped out. It was after nine o’clock. There were lights in the farmhouse still, but they were all upstairs.

“We can at least get a drink now,” he said. And the children crept quietly to the noisy little brook not far from the haystack.

“Cup,” said Benny.

“No, you’ll have to lie down and drink with your mouth,” Jess explained. And so they did. Never did water taste so cool and delicious as it did that night to the thirsty children.

When they had finished drinking they jumped the brook, ran quickly over the fields to the wall, and once more found themselves on the road.

“If we meet any one,” said Jess, “we must all crouch behind bushes until he has gone by.”

They walked along in the darkness with light hearts. They were no longer tired or hungry. Their one thought was to get away from their grandfather, if possible.

“If we can find a big town,” said Violet, “won’t it be better to stay in than a little town?”

“Why?” asked Henry, puffing up the hill.

“Well, you see, there are so many people in a big town, nobody will notice us—”

“And in a little village everyone would be talking about us,” finished Henry admiringly. “You’ve got brains, Violet!”

He had hardly said this, when a wagon was heard behind them in the distance. It was coming from Middlesex. Without a word, the four children sank down behind the bushes like frightened rabbits. They could plainly hear their hearts beat. The horse trotted nearer, and then began to walk up the hill.

“If we hear nothing in Townsend,” they heard a man say, “we have plainly done our duty.”

It was the baker’s voice!

“More than our duty,” said the baker’s wife, “tiring out a horse with going a full day, from morning until night!”

There was silence as the horse pulled the creaky wagon.

“At least we will go on to Townsend tonight,” continued the baker, “and tell them to watch out. We need not go to Intervale, for they never could walk so far.”

“We are well rid of them, I should say,” replied his wife. “They may not have come this way. The milkman did not see them, did he?”

The baker’s reply was lost, for the horse had reached the hilltop, where he broke into a canter.

It was some minutes before the children dared to creep out of the bushes again.

“One thing is sure,” said Henry, when he got his breath. “We will not go to Townsend.”

“And we will go to Intervale,” said Jess.

With a definite goal in mind at last, the children set out again with a better spirit. They walked until two o’clock in the morning, stopping often this time to rest and to drink from the horses’ watering troughs. And then they came upon a fork in the road with a white signpost shining in the moonlight.

“Townsend, four miles; Intervale, six miles,” read Henry aloud. “Any one feel able to walk six more miles?”

He grinned. No one had the least idea how far they had already walked.

“We’ll go that way at least,” said Jess finally.

“That we will,” agreed Henry, picking up his brother for a change, and carrying him “pig-back.”

Violet went ahead. The new road was a pleasant woody one, with grass growing in the middle. The children could not see the grass, but they could feel it as they walked. “Not many people pass this way, I guess,” remarked Violet. Just then she caught her toe in something and almost fell, but Jess caught her.

The two girls stooped down to examine the obstruction.

“Hay!” said Jess.

“Hay!” repeated Violet.

“Hey!” cried Henry, coming up. “What did you say?”

“It must have fallen off somebody’s load,” said Jess.

“We’ll take it with us,” Henry decided wisely. “Load on all you can carry, Jess.”

“For Benny,” thought Violet to herself. So the odd little party trudged on for nearly three hours, laden with hay, until they found that the road ended in a cart path through the woods.

“Oh, dear!” exclaimed Jess, almost ready to cry with disappointment.

“What’s the matter?” demanded Henry in astonishment. “Isn’t the woods a good place to sleep? We can’t sleep in the road, you know.”

“It does seem nice and far away from people,” admitted Jess, “and it’s almost morning.”

As they stood still at the entrance to the woods, they heard the rumble of a train. It roared down the valley at a great rate and passed them on the other side of the woods, thundering along toward the city.

“Never mind the train, either,” remarked Henry. “It isn’t so awfully near; and even if it were, it couldn’t see us.”

He set his brother down and peered into the woods. It was very warm.

“Lizzen!” said Benny.

“Listen!” echoed Violet.

“More water!” Benny cried, catching his big brother by the hand.

“It is only another brook,” said Henry with a thankful heart. “He wants a drink.” The trickle of water sounded very pleasant to all the children as they lay down once more to drink.

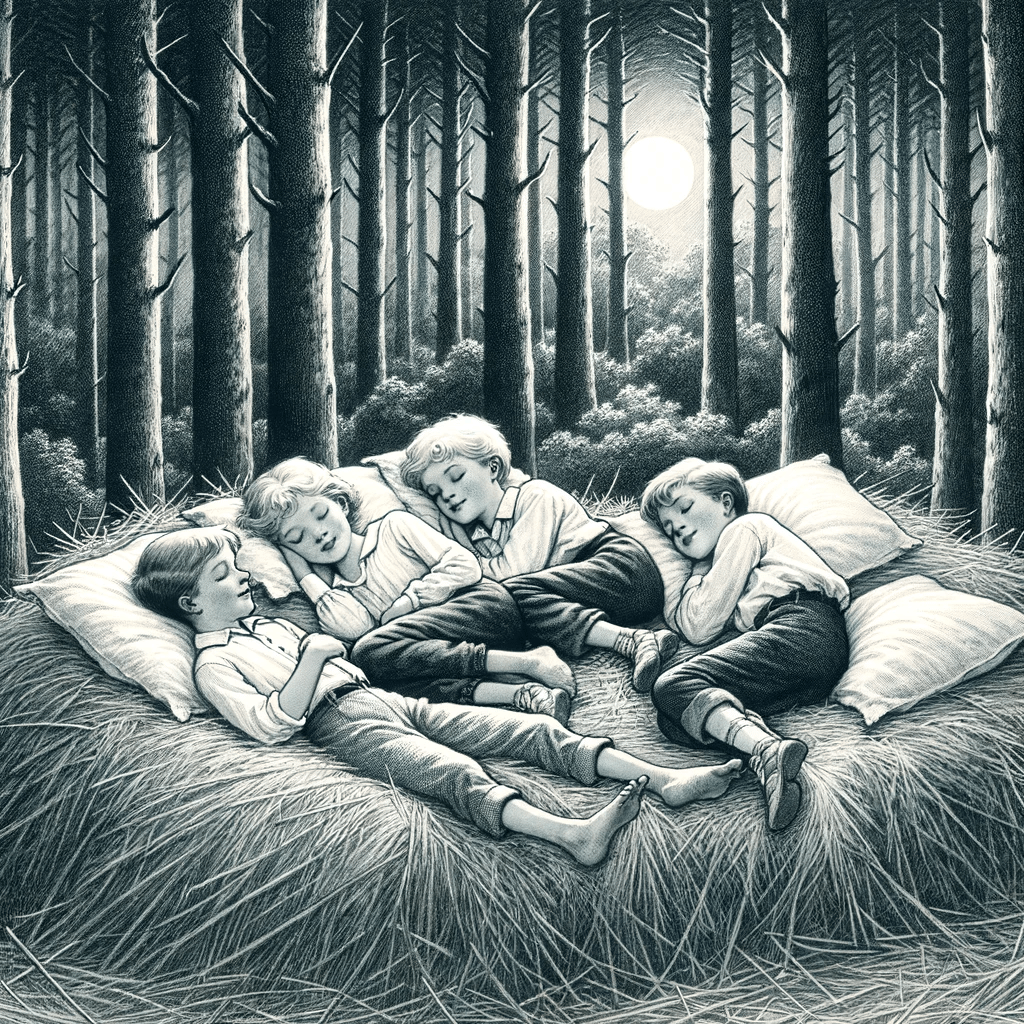

Benny was too sleepy to eat. Jess quickly found a dry spot thick with moss between two stones. Upon this moss the three older children spread the hay in the shape of an oval bed. Benny tumbled into it with a great sigh of satisfaction, while his sisters tucked the hay around him.

“Pine needles up here, Jess,” called Henry from the slope. Each of them quickly scraped together a fragrant pile for a pillow and once more lay down to sleep, with hardly a thought of fear.

“I only hope we won’t have a thunderstorm,” said Jess to herself, as she shut her tired eyes.

And she did not open them for a long time, although the dark gray clouds piled higher and more thickly over the sleeping children.