There are some plants which do not put any winter wraps on their delicate buds; and, strangely enough, these buds do not seem to suffer for lack of clothing.

In a warm country this would not surprise us. If we were going to spend the winter in the West Indies, we should not carry our furs with us, for we should not meet any weather cold enough to make them necessary; and so perhaps in the West Indies the buds have no more need of winter clothing than we ourselves.

But if we were to spend the Christmas holidays somewhere in our Northern mountains, if we were going for skating and coasting to the Catskills or the Adirondacks, we should not fail to take with us our warmest clothes.

And yet, if we walked in the Adirondack woods, we should meet over and over again a shrub bearing naked buds, their folded, delicate leaves quite exposed to the bitter cold.

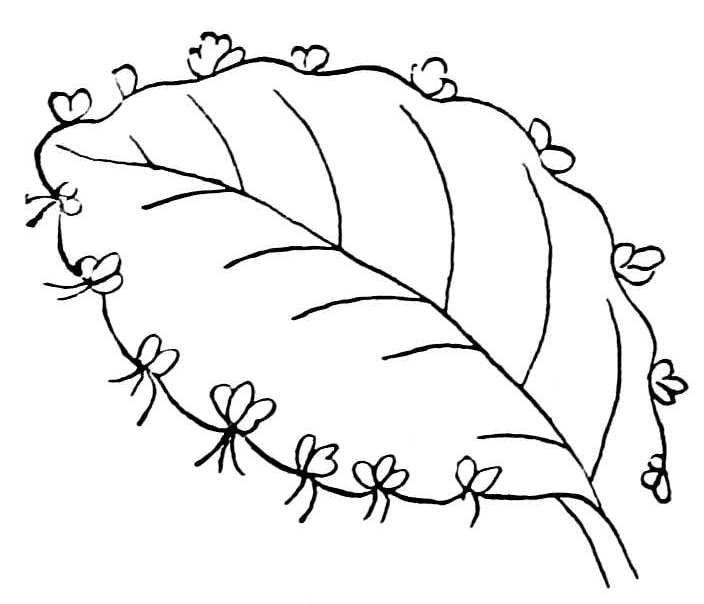

This shrub is the hobblebush, the pretty flowers of which you see on the picture below.

I do not understand any better than you why this hobblebush does not tuck away its baby leaves beneath a warm covering. Neither do I understand how these naked leaves can live through the long, cold winter. I should like very much to satisfy myself as to the reason for this, for they do live and flourish; and I wish that such of you children as know the home of the hobblebush (and it is common in many places) would watch this shrub through the winter, and see if you can discover how it can afford to take less care of its buds than other plants.

There is one tree which seems to shield its buds more carefully in summer than in winter. This tree is the buttonwood. It grows not only in the country, but in many of our city streets and squares. You know it by the way in which its bark peels in long strips from its trunk and branches, and by the button-like balls which hang from the leafless twigs all winter.

If you examine one of these twigs, now that they are bare of leaves, you see the buds quite plainly; but if it is summer time, when the leaves are clinging to the branch, you see no buds, and suppose that they are not yet formed.

But here you are wrong.

“How can that be?” you ask. You looked carefully, and nowhere was there any sign of a bud.

But you did not look everywhere, after all.

If very carefully you had pulled off one of the leaves, you would have found the young bud tucked safely away beneath the hollow end of the leafstalk. This leafstalk fitted over it more neatly than a candle snuffer over a candle.

Try this for yourselves next summer. I think you will be pleased with this pretty arrangement.

We learned that the potato, even though it is buried in the earth and does not look like it, is really one of the thickened stems of the potato plant.

The “eyes” of the potato look as little like buds as the potato itself looks like a stem. Yet these “eyes” are true buds; for, if we leave our potatoes in the dark cellar till spring, the “eyes” will send out slender shoots in the same way that the buds on the branches of trees send out young shoots.

As I told you before, the usual place for a bud is just between the stem and the leafstalk, or the scar left by the leafstalk; but if a stem is cut or wounded, oftentimes it sends out buds in other than the usual places.

This habit accounts for the growth of young shoots from stumps of trees, and from parts of the plant which ordinarily do not give birth to buds.

Some buds never open while fastened to the stem of the parent plant; but after a time they fall to the ground, strike root, and send up a fresh young plant.

The tiger lily, the plant that grows so often in old gardens, bears such buds as these. We call them “bulblets” when they act in this strange fashion.

Perhaps even more surprising than this is the fact that leaves sometimes produce buds.

In certain warmer countries grows a plant called the Bryophyllum. If you look carefully at the thick, fleshy leaves of this plant, along its notched edges you will see certain little dark spots; and if you cut off one of these leaves and pin it on your window curtain, what do you suppose will happen?

Well, right under your eyes will happen one of the strangest things I have ever seen.

From the row of dark spots along the leaf’s edge, springs a row of tiny, perfect plants.

And when these tiny plants are fairly started, if you lay the leaf on moist earth, they will send their roots into the ground, break away from the fading leaf, and form a whole colony of new plants.

Now, those dark spots along the leaf’s edge were tiny buds; and the thick leaf was so full of rich food, that when it was broken off from the parent plant, and all of this food was forced into the buds, these were strong enough to send out roots and leaves, and to set up in life for themselves.

It will not be difficult for your teacher to secure some of these leaves of the Bryophyllum, and to show you in the schoolroom this strange performance.

All children enjoy wonderful tricks, and I know of nothing much prettier or more astonishing than this trick of the Bryophyllum.