Down by the brook and along the sides of the mountain grows a tall shrub which is called the witch-hazel. I hope some of you know it by sight. I am sure that many of you know its name on account of the extract which is applied so often to bruises and burns.

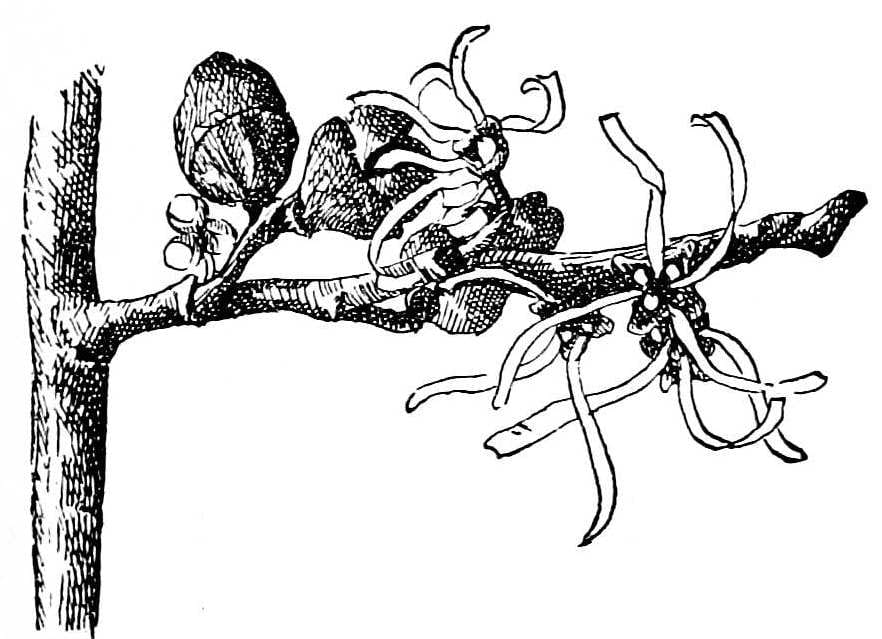

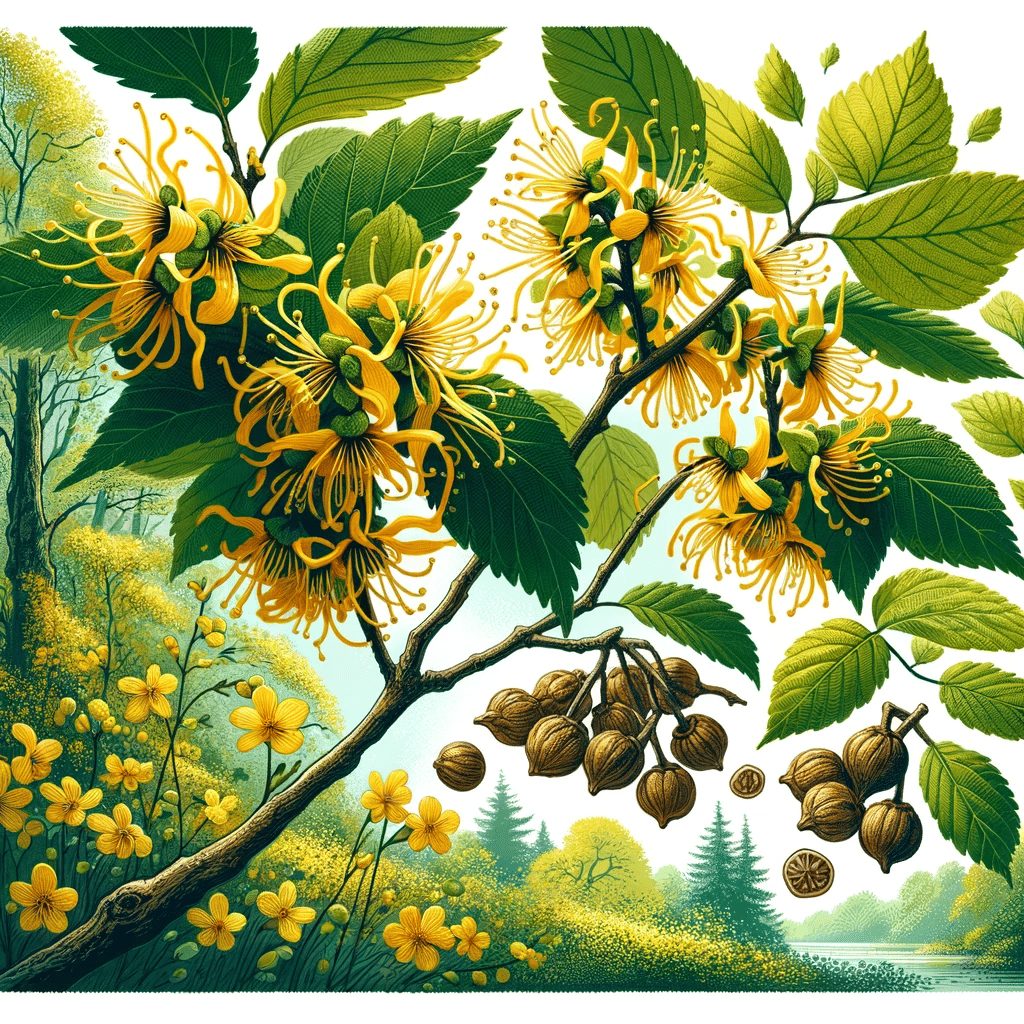

This picture shows you a witch-hazel branch bearing both flowers and fruit; for, unlike any other plant I know, the flower of the witch-hazel appears late in the fall, when its little nuts are almost ripe. These nuts come from the flowers of the previous year.

It is always to me a fresh surprise and delight to come upon these golden blossoms when wandering through the fall woods.

Often the shrub has lost all its leaves before these appear. You almost feel as if the yellow flowers had made a mistake, and had come out six months ahead of time, fancying it to be April instead of October. In each little cluster grow several blossoms, with flower leaves so long and narrow that they look like waving yellow ribbons.

But to-day we wish chiefly to notice the fruit or nut of the witch-hazel.

Now, the question is, how does the witch-hazel manage to send the seeds which lie inside this nut out into the world? I think you will be surprised to learn just how it does this.

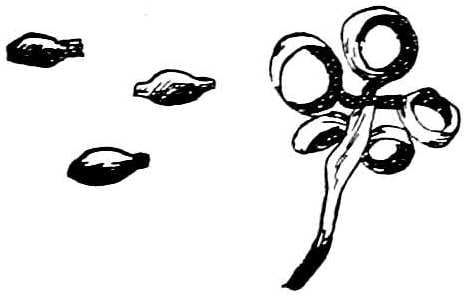

If you have a nut before you, you see for yourselves that this fruit is not bright-colored and juicy-looking, or apparently good to eat, and thus likely to tempt either boy or bird to carry it off; you see that it is not covered with hooks that can lay hold of your clothing, and so steal a ride; and you see that it has no silky sails to float it through the air, nor any wings to carry it upon the wind.

And so the witch-hazel, knowing that neither boy nor girl, nor bird nor beast nor wind, will come to the rescue of its little ones, is obliged to take matters into its own hands; and this is what it does. It forces open the ripe nut with such violence, that its little black seeds are sent rattling off into the air, and do not fall to the ground till they have traveled some distance from home. Really they are shot out into the world.

If you wish to make sure that this is actually so, gather some of these nuts, and take them home with you. It will not be long before they begin to pop open, and shoot out their little seeds.

Did you ever hear of Thoreau? He was a man who left his friends and family to live by himself in the woods he so dearly loved. Here he grew to know each bird and beast, each flower and tree, almost as if they were his brothers and sisters. One day he took home with him some of these nuts, and later he wrote about them in his journal,—

“Heard in the night a snapping sound, and the fall of some small body on the floor from time to time. In the morning I found it was produced by the witch-hazel nuts on my desk springing open and casting their seeds quite across my chamber.”

Now, I do not want any of you children to go off by yourselves to live in the woods; but I should like to think that you could learn to love these woods and their inmates with something of the love that Thoreau felt. And if you watch their ways with half the care that he did, some such love is sure to come.

Although the witch-hazel’s rough way of dealing with its young is not very common among the plants, we find much the same thing done by the wild geranium, or crane’s bill, and by the touch-me-not.

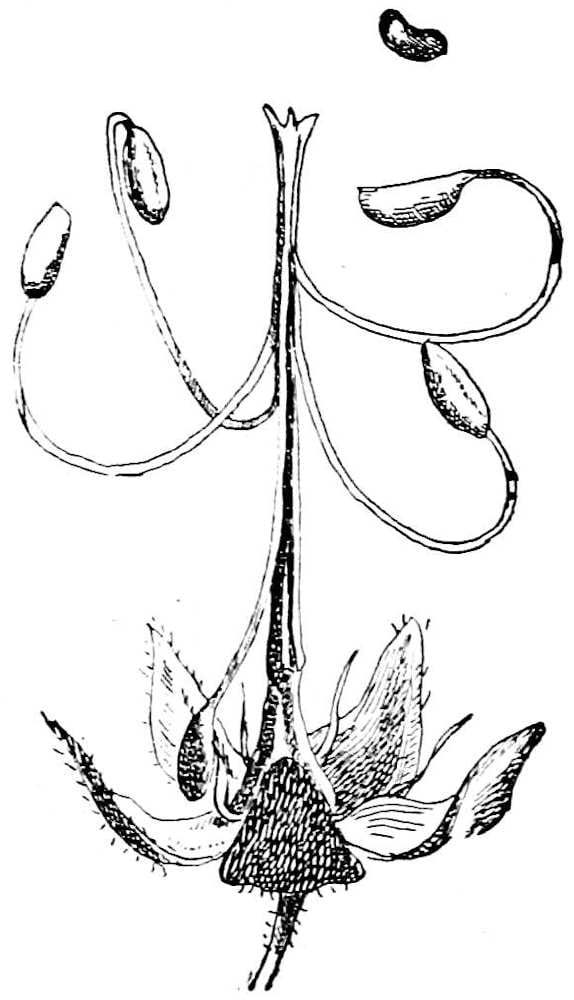

The wild geranium is the pretty purplish, or at times pink flower which blossoms along the roads and in the woods in May and early June.

Its seedbox has five divisions. In fruit this seedbox tapers above into a long beak, which gives the plant its name of “crane’s bill.” When the fruit is quite ripe, it splits away from the central part of this beak in five separate pieces, which spring upward so suddenly that the seeds are jerked out of the five cells, and flung upon the earth at a distance of several feet. The picture shows you how this is done. But a little search through the summer woods will bring you to the plant itself; and if you are patient, perhaps you will see how the wild geranium gets rid of its children. But though this habit may at first seem to you somewhat unmotherly, if you stop to think about it you will see that really the parent plant is doing its best for its little ones. If they should fall directly upon the ground beneath, their chances in life would be few. About plants, as about people, you must not make up your minds too quickly.

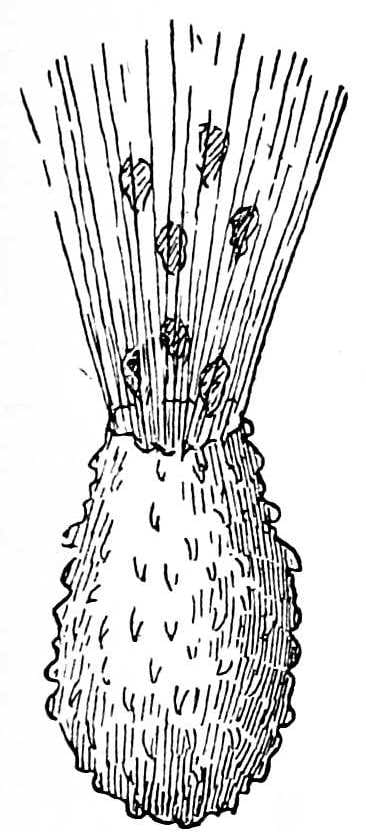

Another plant that all of you country children ought to know, is the touch-me-not, or jewelweed. Sometimes this is called “lady’s eardrop,” because its pretty, red-gold, jewel-like flowers remind us of the drops that once upon a time ladies wore in their ears. These flowers we find in summer in wet, woody places. In the fall the fruit appears. This fruit is a little pod which holds several seeds. When this pod is ripe, it bursts open and coils up with an elastic spring which sends these seeds also far from home.

This performance of the touch-me-not you can easily see; for its name “touch-me-not” comes from the fact that if you touch too roughly one of its well-grown pods, this will spring open and jerk out its seeds in the way I have just described.

In Europe grows a curious plant called the “squirting cucumber”. Its fruit is a small cucumber, which becomes much inflated with water. When this is detached from its stalk, its contents are “squirted” out as if from a fountain, and the seeds are thus thrown to a distance of many feet.