What do you say this morning to going to the woods rather than to either garden or orchard?

Not that I am ready to take back anything I said at the beginning of this book about the delights of the orchard as a playground. For actual play I know of no better place. An apple tree is as good a horse as it is a house, as good a ship as it is a mountain. Other trees may be taller, finer to look at, more exciting to climb; but they do not know how to fit themselves to the need of the moment as does an apple tree.

But for anything besides play, the woods, the real woods, are even better than the orchard. The truth is, in the woods you have such a good time just living, that you hardly need to play; at least you do if you are made in the right way.

So now we are off for the woods. We have only to cross a field and climb a fence, and we are in the lane which leads where we wish to go.

Through the trees comes a golden light. This is made partly by the sunshine, but mostly by the leaves turned yellow. These yellow leaves mean that summer is over. It is in summer, when we are having our vacation, that the leaves work hardest; for leaves have work to do, as we shall learn later. But now they are taking a rest, and wearing their holiday colors.

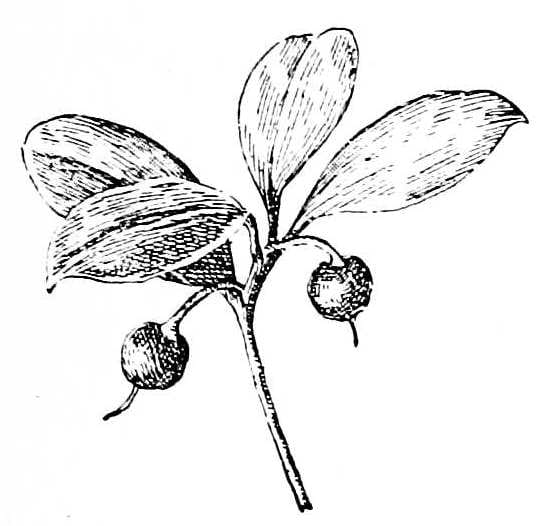

Twisting in and out over the rails of the fence are clusters of berries which are very beautiful when you look at them closely. Each berry is an orange-colored case which opens so as to show a scarlet seedbox within. A little earlier in the year you could not see this bright-colored seedbox. It is only a short time since the outer case opened and displayed its contents. These are the berries of the bittersweet. Last June you would hardly have noticed its little greenish flowers, and would have been surprised to learn that they could change into such gay fruit.

Do you see a shrub close by covered with berries? These berries are dark blue. They grow on bright-red stalks. If we wait here long enough, it is likely that we shall see the birds alight upon some upper twig and make their dinner on the dogwood berries; for this is one of the Dogwood family,—the red-stalked dogwood, we call it. When its berries turn a very dark blue, then the birds know they are ready to be eaten, just as we know the same thing by the rosy cheeks of the apple.

You can be pretty sure that any fruit so gayly colored as to make us look at it twice, is trying to persuade some one—some boy or girl, or bird, or perhaps even some bear—to come and eat it.

You have not forgotten, I hope, why these fruits are so anxious to be eaten? You remember that when their seeds become ripe, and ready to make new plants, then they put on bright colors that say for them, “Come and eat us, for our little seeds want to get out of their prison!”

Once upon a time these seeds did not find their cozy seed cases a prison. So once upon a time the baby robins were content to stay safe in their nest. And once upon a time all the playground you needed was a little corner behind your mother’s chair. But seeds, like birds and babies, outgrow their surroundings, and need more room.

Here is a tall shrub with bright-colored leaves, and clusters of dark red fruit that grow high above our heads. It looks something like certain materials used in fancywork. This shrub is called the sumac; and if you pick and pull apart one of its fruit clusters, you find that it is made up of a quantity of seeds that are covered with little red hairs. There is nothing soft and juicy about the fruit of the sumac. Whether it is ever used as food by the birds, I do not know. I wish some child would make it his business to find out about this. Some of you are sure to live near a clump of sumacs. By watching them closely for a few weeks, you ought to discover if any birds feed upon their fruit.

If you do make any such discovery, I hope you will write a letter telling me of it; and then, if another edition of this book is published, I shall be able to tell other children more about the fruit of the sumac than I can tell you to-day.

There are many interesting things about plants yet to be found out; and you children will find it far pleasanter to make your own discoveries, using your own bright eyes, than to read about the discoveries of other people. Every field, each bit of woods, the road we know so well leading from home to the schoolhouse, and even the city squares and parks, are full of interesting things that as yet we have never seen, even though we may have been over the ground a hundred times before.

Now let us leave the lane, and strike into the woods in search of new fruits. This morning we will look especially for those fruits which by their bright colors and pleasant looks seem to be calling out to whomsoever it may concern, “Come and eat us!”

Close at hand is one of our prettiest plants. Its leaves look as though they were trying to be in the height of the fall fashion, and to outdo even the trees in brightness of color. These leaves are set in circles about the slim stem. From the top of this grow some purple berries.

This plant is the Indian cucumber root. If one of you boys will dig it up with your knife, you will find that its root is shaped a little like a cucumber. Though I have never made the experiment myself, I am told that it tastes something like the cucumber. It is possible, that, as its name suggests, it was used as food by the Indians. To hunt up the beginnings of plant names is often amusing. So many of these are Indian, that in our rambles through the woods we are constantly reminded of the days when the red man was finding his chief support in their plants and animals.

In June we find the flower of the Indian cucumber root. This is a little yellowish blossom, one of the Lily family. Small though it is, for one who knows something of botany it is easy to recognize it as a lily. Indeed, the look of the plant suggests the wood and meadow lilies. This is partly because of the way in which the leaves grow about its stem, much as they do in these other lilies.

Now look at the beautiful carpet which is spread beneath your feet. Here you will wish to step very lightly; for otherwise you might crush some of those bright red berries which are set thickly among the little white-veined leaves.

These are called “partridge berries,”—a name given them because they are eaten by partridges. But the bare winter woods offer few tempting morsels for bird meals; and it seems likely that the nuthatch and snowbird, the chickadee and winter wren, hail with delight these bright berries, and share with the partridges the welcome feast.

Please look closely at one of the berries and tell me whether you see anything unusual.

“There are two little holes on top.”

Yes, that is just what I hoped you would notice. I do not know of any other berries in which you could find these two little holes; and as I do not believe it would be possible for you to guess what made these holes, I will tell you about them.

The flowers of the partridge vine always grow in twos. The seedboxes of these two flowers are joined in one. So when the flowers fade away, only the one seedbox is left. When this ripens, it becomes the partridge berry; and the two little holes show where the two flowers were fastened to the seedbox.

Try not to forget this, and early next July be sure to go to the woods and look for the little sister flowers. Perhaps their delicious fragrance will help you in your hunt for their hiding place. Then see for yourselves how the two blossoms have but one seedbox between them.

Now, we must take care not to wet our feet, for the ground is getting damp. We are coming to that lovely spot where the brook winds beneath the hemlocks after making its leap down the rocks. What is that flaming red spot against the gray rock over there?

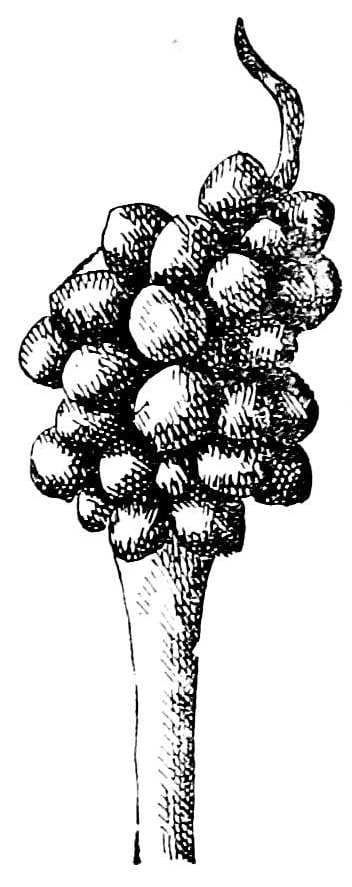

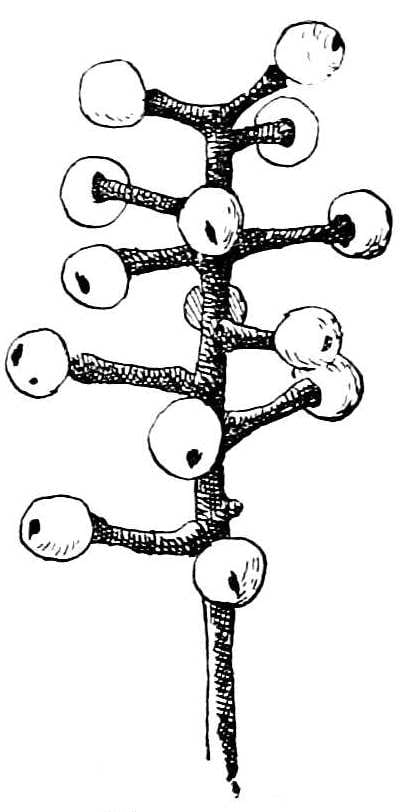

As we draw nearer, we see that a quantity of scarlet berries are closely packed upon a thick stalk.

Do you know the name of the plant which owns this flaming fruit?

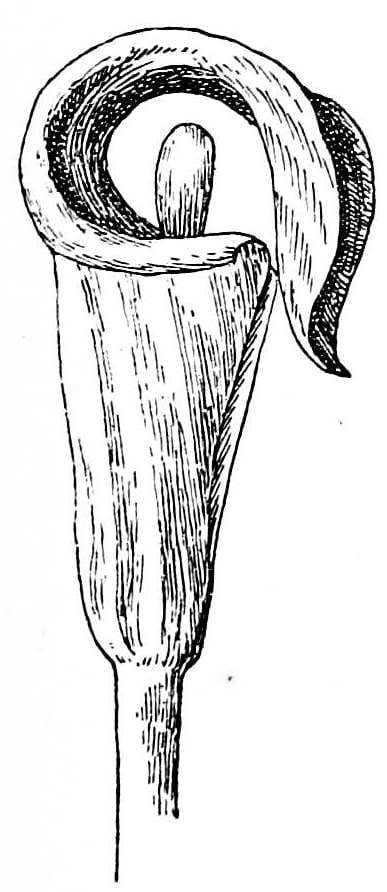

If you were in these woods last May, at every turn you met one of those quaint little fellows we call “Jack-in-the-pulpit.”

Jack himself, you remember, was hidden almost out of sight by his “pulpit.” This pulpit was made of a leaf striped green or purple, or both; and this leaf curled about and above Jack.

After a time the pretty leaf pulpit faded away, and Jack was left standing all alone.

The lower part of Jack is covered with tiny flowers. After these had been properly dusted by the little flies (for flies, not bees, visit Jack), just as the apple blossom began to change into the apple, so these tiny flowers began to turn into bright berries.

While this was happening, Jack’s upper part began to wither away; and at last all of it that was left was the queer little tail which you see at the top of the bunch of berries.

It is said that the Native Americans boiled these berries, and then thought them very good to eat.

If we were lost in the woods, and obliged to live upon the plants about us, I dare say we should eat, and perhaps enjoy eating, many things which now seem quite impossible; but until this happens I advise you not to experiment with strange leaves and roots and berries. Every little while one reads of the death of some child as the result of eating a poisonous plant.

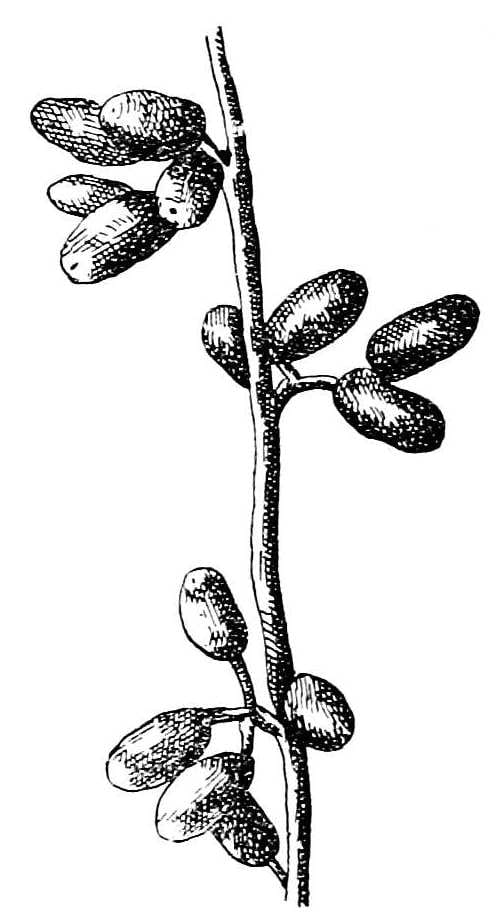

The next picture shows you the fruit of Solomon’s seal. These dark-blue berries hang from beneath the leafy stem, just as the little flowers hung their yellow heads last May.

Next come the speckled red berries of the false Solomon’s seal, a big cousin of the smaller plant. As you see, this bears its fruit quite differently, all in a cluster at the upper part of the stem. These two plants seem to be great chums, constantly growing side by side.

We have been so busy and so happy that the morning has flown, and now we must be finding our way home to dinner; for, unlike the birds, we are not satisfied to dine on berries alone.

At almost every step we long to stop and look at some new plant in fruit; for, now that we have learned how to look for them, berries of different sorts seem thick on every side.

Low at our feet are the red ones of the wintergreen.

On taller plants grow the odd white ones, with blackish spots, of the white baneberry, or the red ones of the red baneberry.

Still higher glisten the dark, glass-like clusters of the spikenard.

Along the lane are glowing barberries and thorns bright with their “haws” (for the fruit of the thorn is called a “haw”). These look something like little apples.

Here, too, is the black alder, studded with its red, waxy beads. But we must hurry on, not stopping by the way. And you can be sure that those birds we hear chirruping above us are glad enough to be left to finish their dinner in peace.