Already we have learned that some stems grow under ground, and that by most people these are called roots.

And among those which grow above the ground we see many different kinds.

The stem of Indian corn grows straight up in the air, and needs no help in standing erect.

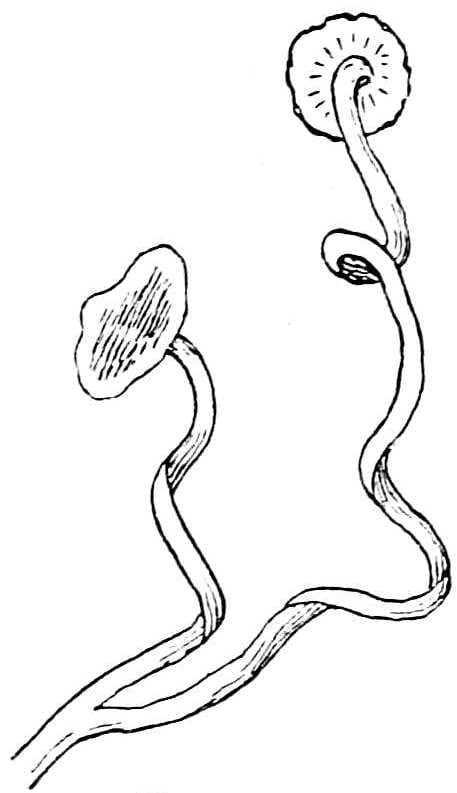

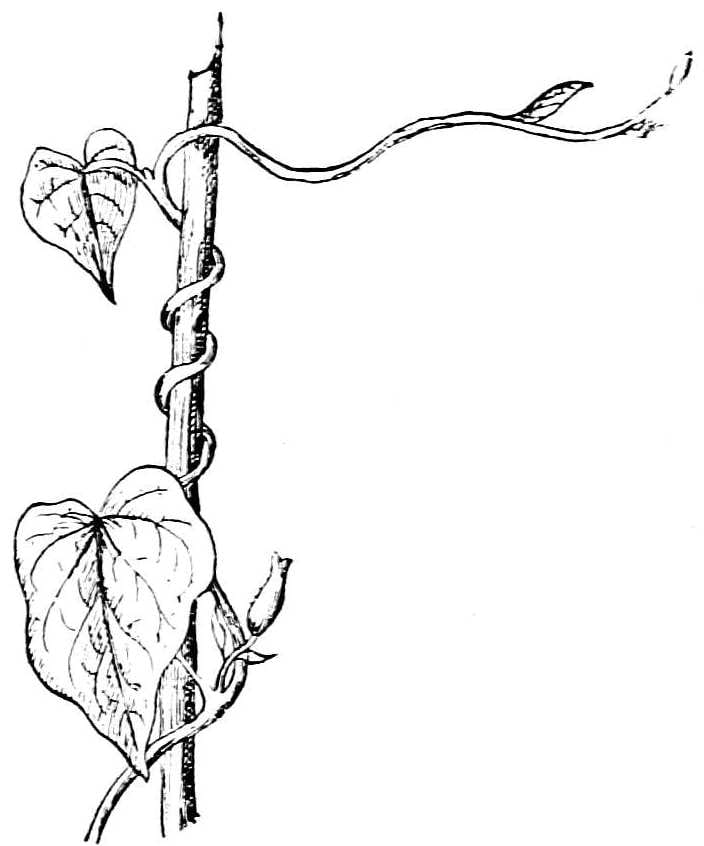

The below picture shows you the morning-glory plant, the stem of which is unable to hold itself upright without assistance. A great many plants seem to need this same sort of help; and it is very interesting to watch their behavior.

The stem of the young morning-glory sweeps slowly through the air in circles, in search of some support.

You remember that the curious dodder acted in this same way, and that its movements reminded us of the manner in which a blind man feels about him.

When the morning-glory finds just the support it needs, it lays hold of it, and twists about it, and then climbs upward with great satisfaction.

I want you to watch this curious performance. It is sure to amuse you. The plant seems to know so well what it is about, and it acts so sensibly when it finds what it wants.

But if it happens to meet a glass tube, or something too smooth to give it the help it needs, it slips off it, and seems almost as discouraged as a boy would be who fails in his attempt to climb a slippery tree or telegraph pole.

The bean is another plant whose stem is not strong enough to hold it erect without help. But, unlike the morning-glory, the stem of the bean does not twist about the first stick it finds. Instead it sends out many shorter stems which do this work of reaching after and twining about some support. In this same way the pea is able to hold up its head in the world.

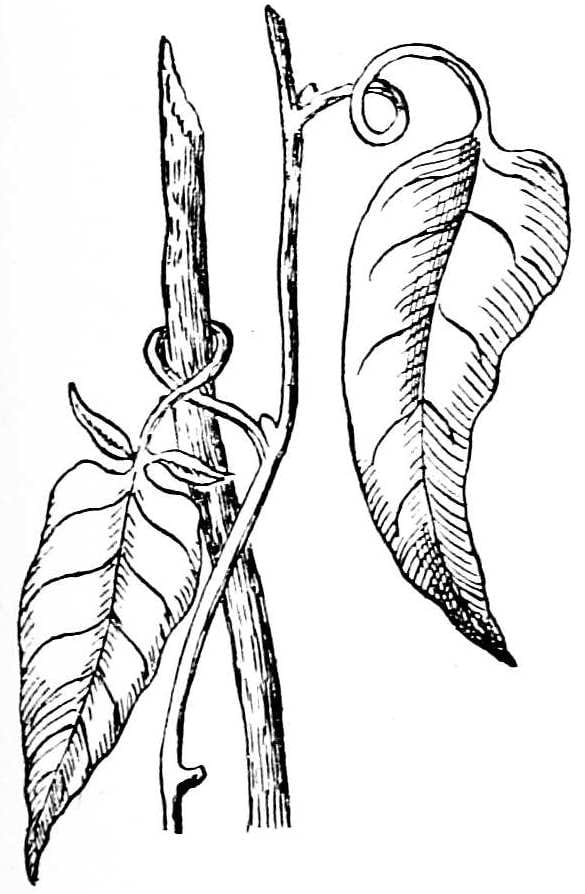

Other plants are supported by their leafstalks. These twist about whatever sticks or branches they can find, and so prevent the plant from falling. The picture shows you how the garden nightshade climbs by its leafstalk. The beautiful clematis clambers all over the roadside thicket in the same way.

The English ivy and the poison ivy, as we have learned already, climb by the help of roots which their stems send out into the trunks of trees and the crevices of buildings.

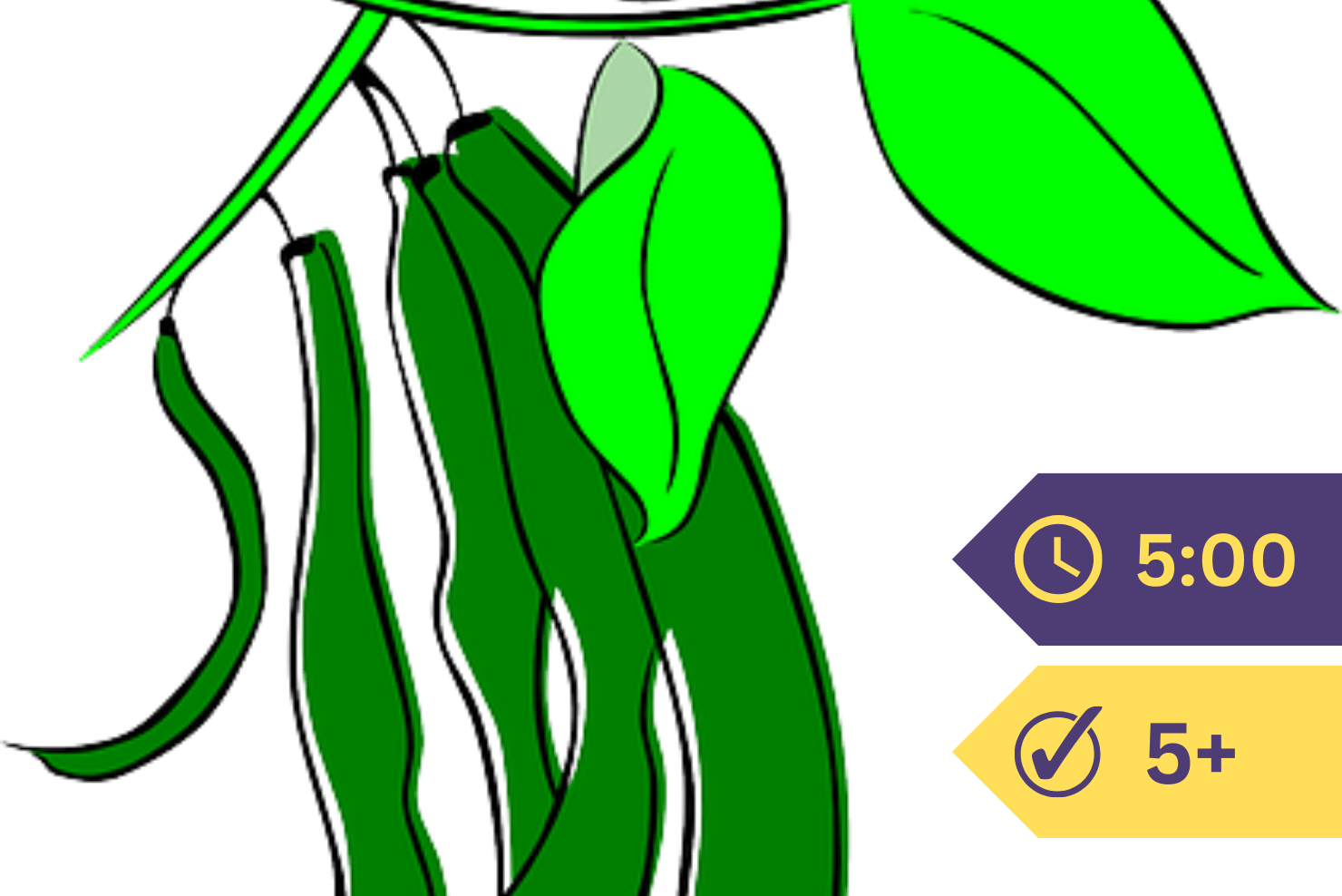

The stems of the Virginia creeper and of the Japanese ivy give birth to smaller stems, such as you see in the picture below. When the tips of these reach the wall, or the tree trunk up which the plant is trying to climb, they broaden out into little flat, round plates, which, like tiny claws, cling to the surface.

I hope your teacher will tell you where you can find one of these two plants, for in the country the creeper is plentiful, and the Japanese ivy is planted freely in our cities; and I hope you will go and see how firmly these little flattened stems cling to the wall or to the tree trunk. Try gently to pull off one of these determined little stems, and I think you will admire it for its firm grip.

There are other than climbing plants whose stems are not strong enough to stand up straight without help.

Think of the beautiful water lily. If you have ever spent a morning in a boat (as I hope you have, for it is a delightful way to spend a morning) hunting water lilies, you will remember that these flowers float on top of the water; and when you reach over to pick them, you find the tall flower stems standing quite erect in the water.

But what happened when you broke them off, and held them in your hand?

Why, these long stems proved to have no strength at all. They flopped over quite as helplessly as the morning-glory vine would do if you unwound it from the wires up which it was climbing; and you saw that they had only been able to stand up straight because of the help the water had given them.