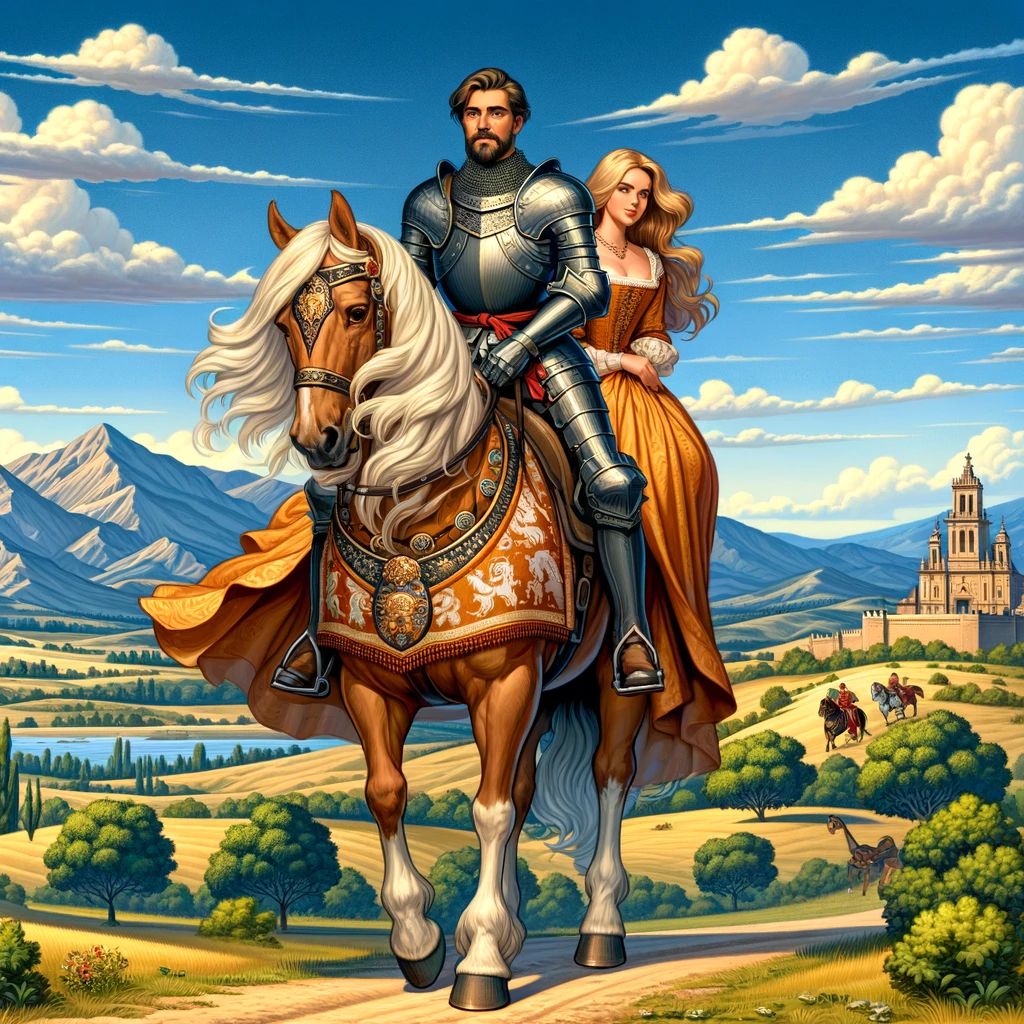

The curate rode first on the mule, and with him rode Don Quixote and the princess. The others, Cardenio, the barber, and Sancho Panza, followed on foot.

And as they rode, Don Quixote said to the damsel: “Madam, let me entreat your highness to lead the way that most pleaseth you.”

Before she could answer, the curate said: “Towards what kingdoms would you travel? Are you for your native land of Micomicon?”

She, who knew very well what to answer, being no babe, replied: “Yes, sir, my way lies towards that kingdom.”

“If it be so,” said the curate, “you must pass through the village where I dwell, and from thence your ladyship must take the road to Carthagena, where you may embark. And, if you have a prosperous journey, you may come within the space of nine years to the Lake Meona, I mean Meolidas, which stands on this side of your highness’s kingdom some hundred days’ journey or more.”

“You are mistaken, good sir,” said she, “for it is not yet fully two years since I left there, and, though I never had fair weather, I have arrived in time to see what I so longed for, the presence of the renowned Don Quixote of the Mancha, whose glory was known to me as soon as my foot touched the shores of Spain.”

“No more,” cried Don Quixote. “I cannot abide to hear myself praised, for I am a sworn enemy to flattery. And though I know what you speak is but truth, yet it offends mine ears. And I can tell you this, at least, that whether I have valour or not, I will use it in your service, even to the loss of my life. But let me know, master curate, what has brought you here?”

“You must know, then,” replied the curate, “that Master Nicholas, the barber, and myself travelled towards Seville to recover certain sums of money which a kinsman of mine in the Indies had sent me. And passing yesterday through this way we were set upon by four robbers, who took everything that we had. And it is said about here, that those who robbed us were certain galley slaves, who they say were set at liberty, almost on this very spot, by a man so valiant that in spite of the guard he released them all. And doubtless he must be out of his wits, or else he must be as great a knave as they, to loose the wolf among the sheep, and rebel against his king by taking from the galleys their lawful prey.”

Sancho had told the curate of an adventure they had had with galley slaves, and the curate spoke of it to see what Don Quixote would say. The knight, however, durst not confess his part in the adventure, but rode on, changing colour at every word the curate spoke.

When the curate had finished, Sancho burst out: “By my father, master curate, he that did that deed was my master, and that not for want of warning, for I told him beforehand that it was a sin to deliver them, and that they were great rogues who had been sent to the galleys to punish them for their crimes.”

“You bottlehead!” replied Don Quixote. “It is not the duty of knights-errant to examine whether the afflicted, enslaved, and oppressed whom they meet by the way are in sorrow for their own default; they must relieve them because they are needy and in distress, looking at their sorrow and not at their crimes. And if any but the holy master curate shall find fault with me on this account, I will tell him that he knows nought of knighthood, and that he lies in his throat, and this I will make him know by the power of my sword.”

Dorothea, who was discreet enough to see they were carrying the jest too far, now said: “Remember, sir knight, the boon you promised me, never to engage in any other adventure, be it ever so urgent, until you have seen me righted. And had master curate known that it was the mighty arm of Don Quixote that freed the galley slaves, I feel sure he would have bit his tongue through ere he spoke words which might cause you anger.”

“That I dare swear,” said the curate.

“Madam,” replied Don Quixote, “I will hold my peace and keep my anger to myself, and will ride on peaceably and quietly until I have done the thing I promised. Tell me, therefore, without delay, what are your troubles and on whom am I to take revenge.”

To this Dorothea replied: “Willingly will I do what you ask, so you will give me your attention.”

At this Cardenio and the barber drew near to hear the witty Dorothea tell her tale, and Sancho, who was as much deceived as his master, was the most eager of all to listen.

She, after settling herself in her saddle, began with a lively air to speak as follows: “In the first place, I would have you know, gentlemen, that my name is—” Here she stopped a moment, for she had forgotten what name the curate had given her.

He, seeing her trouble, said quickly: “It is no wonder, great lady, that you hesitate to tell your misfortunes. Great sufferers often lose their memory, so that they even forget their own names, as seems to have happened to your ladyship, who has forgotten that she is called the Princess Micomicona, heiress of the great Kingdom of Micomicon.”

“True,” said the damsel, “but let me proceed. The king, my father, was called Tinacrio the Sage, and was learned in the magic art. By this he discovered that my mother, the Queen Xaramilla, would die before him, and that I should soon afterwards be left an orphan. This did not trouble him so much as the knowledge that a certain giant, called Pandafilando of the Sour Face, lord of a great island near our border, when he should hear that I was an orphan, would pass over with a mighty force into my kingdom and take it from me. My father warned me that when this came to pass I should not stay to defend myself, and so cause the slaughter of my people, but should at once set out for Spain, where I should meet with a knight whose fame would then extend through all that kingdom. His name, he said, should be Don Quixote, and he would be tall of stature, have a withered face, and on his right side, a little under his left shoulder, he should have a tawny spot with certain hairs like bristles.”

On hearing this, Don Quixote said: “Hold my horse, son Sancho, and help me to strip, for I would know if I am the knight of whom the sage king spoke.”

“There is no need,” said Sancho, “for I know that your worship has such a mark near your backbone.”

“It is enough,” said Dorothea, “for among friends we must not be too particular, and whether it is on your shoulder or your backbone is of no importance. And, indeed, no sooner did I land in Osuna than I heard of Don Quixote’s fame, and felt sure that he was the man.”

“But how did you land in Osuna, madam,” asked Don Quixote, “seeing that it is not a sea town?”

“Sir,” said the curate, “the princess would say that she landed at Malaga, and that Osuna was the first place wherein she heard tidings of your worship.”

“That is so,” said Dorothea; “and now nothing remains but to guide you to Pandafilando of the Sour Face, that I may see you slay him, and once again enter into my kingdom. For all must succeed as the wise Tinacrio, my father, has foretold, and if the knight of the prophecy, when he has killed the giant, so desires, then it will be my lot to become his wife, and he will at once possess both me and my kingdom.”

“What thinkest thou of this, friend Sancho? Did I not tell thee this would come about? Here we have a kingdom to command and a queen to marry.”

When Sancho heard all this he jumped for joy, and running to Dorothea stopped her mule, and asking her very humbly to give him her hand to kiss, he kneeled down as a sign that he accepted her as his queen and lady.

All around could scarcely hide their laughter at the knight’s madness and the squire’s simplicity, and when Dorothea promised Sancho to make him a great lord, and Sancho gave her thanks, it roused their mirth anew.

“Madam,” continued Don Quixote, who appeared to be full of thought, “I repeat all I have said, and make my vow anew, and when I have cut off the head of Pandafilando I will put you in peaceable possession of your kingdom, but since my memory and will are captive to another, it is not possible for me to marry.”

So disgusted was Sancho with what he heard that he cried out in a great rage: “Surely, Sir Don Quixote, your worship is not in your right senses. Is it possible your worship can refuse to marry a princess like this? A poor chance have I of getting a countship if your worship goes on like this, searching for mushrooms at the bottom of the sea. Is my Lady Dulcinea more beautiful? She cannot hold a candle to her. Marry her! Marry at once, and when you are king make me a governor.”

Don Quixote, who heard such evil things spoken of his Lady Dulcinea, could not bear them any longer, and therefore, lifting up his lance, without speaking a word to Sancho, gave him two blows that brought him to the earth, and if Dorothea had not called to the knight to spare him, without doubt he would have taken his squire’s life.

“Think you, miserable villain,” cried Don Quixote, “that it is to be all sinning on thy side and pardoning on mine? Say, scoffer with the viper’s tongue, who dost thou think hath gained this kingdom and cut off the head of this giant and made thee marquis—for all this I take to be a thing as good as completed—unless it be the worth and valour of Dulcinea using my arm as her instrument? She fights in my person, and I live and breathe in her. From her I hold my life and being. O villain, how ungrateful art thou that seest thyself raised from the dust of the earth to be a nobleman, and speakest evil of her who gives thee such honours!”

Sancho was not too much hurt to hear what his master said. He jumped up nimbly and ran behind Dorothea’s palfrey, and from there said to his master: “Tell me, your worship, if you are not going to marry this great princess, how this kingdom will become yours, and how you can do me any favours. Pray marry this queen now we have her here. I say nothing against Lady Dulcinea’s beauty, for I have never seen her.”

“How, thou wicked traitor, thou hast not seen her!” cried Don Quixote. “Didst thou not but now bring me a message from Her?”

“I mean,” replied Sancho, “not seen her for long enough to judge of her beauty, though, from what I did see, she appeared very lovely.”

“Ah!” said Don Quixote, “then I do excuse thee, but have a care what thou sayest, for, remember, the pitcher may go once too often to the well.”

“No more of this,” said Dorothea. “Run Sancho, kiss your master’s hand, and ask his pardon. Henceforth speak no evil of the Lady Dulcinea, and trust that fortune may find you an estate where you may live like a prince.”

Sancho went up hanging his head and asked his lord’s hand, which he gave him with a grave air, and, after he had kissed it, the knight gave him his blessing, and no more was said about it.

While this was passing, they saw coming along the road on which they were a man riding upon an ass, and when he drew near he seemed to be a gipsy.

But Sancho Panza, whenever he met with any asses, followed them with his eyes and his heart, and he had hardly caught sight of the man when he knew him to be an escaped robber, Gines of Passamonte, and the ass to be none other than his beloved Dapple.

Gines had disguised himself as a gipsy, but Sancho knew him, and called out in a loud voice: “Ah! thief Gines, give up my jewel, let go my life, give up mine ass, give up the comfort of my home. Fly, scoundrel! Begone, thief! Give back what is none of thine.”

He need not have used so many words, for Gines leaped off at the first and raced away from them all as fast as his legs could carry him.

Sancho then ran up to Dapple, and, embracing him, cried: “How hast thou been cared for, my darling and treasure, Dapple of mine eyes, my sweet companion?” With this he stroked and kissed him as if he had been a human being. But the ass held his peace, and allowed Sancho to kiss and cherish him without answering a word.