This morning let us take a stroll in the woods with the idea of noticing the different building plans used by the early flowers.

First we will go to the spot where we know the trailing arbutus is still in blossom. Pick a spray, and tell me the plan of its flower.

“There is a small green cup, or calyx, cut into five little points,” you say; “and there is a corolla made up of five flower leaves.”

But stop here one moment. Is this corolla really made up of five separate flower leaves? Are not the flower leaves joined in a tube below? If this be so, you must say that this corolla is five-lobed, or five-pointed, not that it has five flower leaves.

“And there are ten pins with dust boxes, or stamens.”

Yes, that is quite right.

“And there is one of those pins with a seedbox below, one pistil, that is, but the top of this pistil is divided into five parts.”

Well, then, the building plan of the trailing arbutus runs as follows:—

- Calyx.

- Corolla.

- Stamens.

- Pistil.

So far, it seems the same plan as that used by the cherry tree, yet in certain ways this plan really differs from that of the cherry blossom. The calyx of the cherry is not cut into separate leaves, as is that of the arbutus; and its corolla leaves are quite separate, while those of the arbutus are joined in a tube.

The cherry blossom has more stamens than the arbutus. Each flower has but one pistil. But the pistil of the arbutus, unlike that of the cherry, is five-lobed.

So, although the general plan used by these two flowers is the same, it differs in important details.

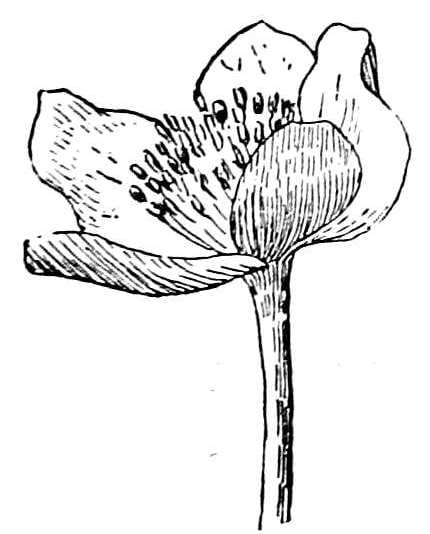

Above you see the flower of the marsh marigold. Its building plan is as follows:—

- Flower leaves.

- Stamens.

- Pistils.

This, you remember, is something like the building plan of the easter lily. The lily has a circle of flower leaves in place of calyx and corolla. So has the marsh marigold. But the lily has six flower leaves, one more than the marsh marigold, and only six stamens, while the marsh marigold has so many stamens that it would tire one to count them.

And the lily has but one pistil (this is tall and slender), while the marsh marigold has many short, thick ones, which you do not see in the picture.

So these two flowers use the same building plan in a general way only. They are quite unlike in important details.

The pretty little liverwort and the delicate anemone use the same building plan as the marsh marigold. This is not strange, as all three flowers belong to the same family.

The yellow adder’s tongue is another lily. It is built on the usual lily plan:—

- Six flower leaves.

- Six stamens.

- One pistil.

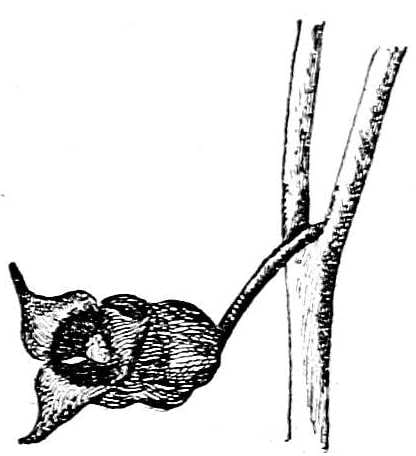

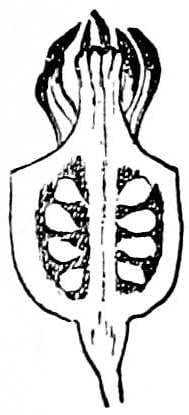

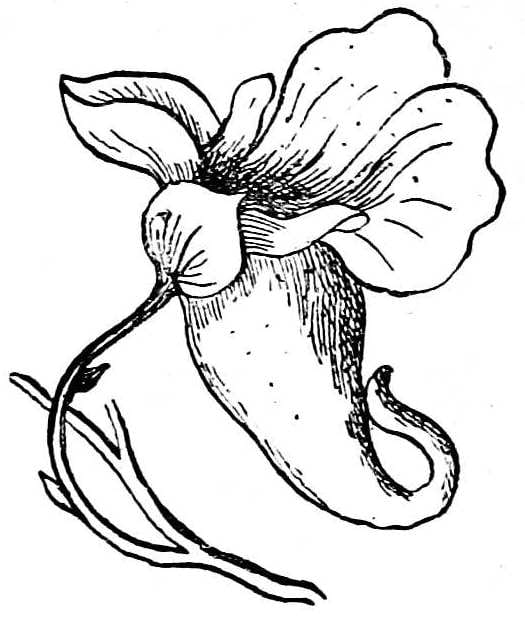

The wild ginger uses the lily plan, inasmuch as it has no separate calyx and corolla; but otherwise it is quite different. It has no separate flower leaves, but one three-pointed flower cup. It has stamens, and one pistil which branches at its tip.

The next picture shows you the seedbox, cut open, of the wild ginger.

To find this flower, your eyes must be brighter than usual. It grows close to the ground, and is usually hidden from sight by the pair of round, woolly leaves shooting up from the underground stem, which tastes like ginger. This thick underground stem is the storehouse whose stock of food makes it possible for the plant to flower and leaf so early in the year.

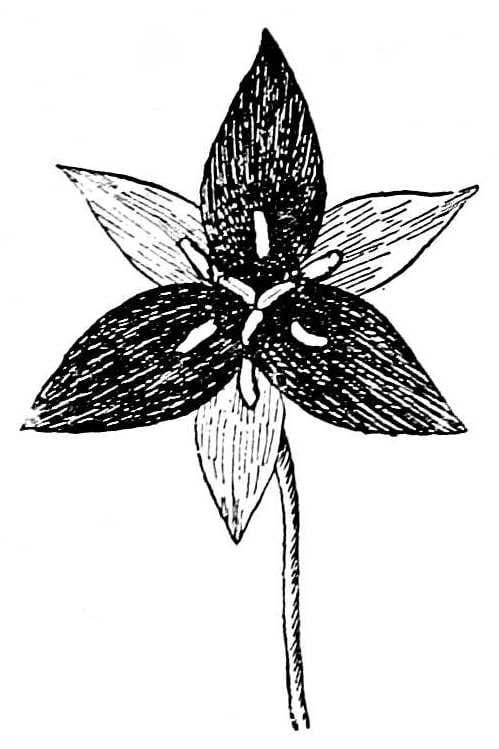

The picture below shows you the pretty wake-robin. This is a lily. But it is unlike the lilies we already know, in that its calyx and corolla are quite distinct, each having three separate leaves. It has six stamens, and one pistil with three branches.

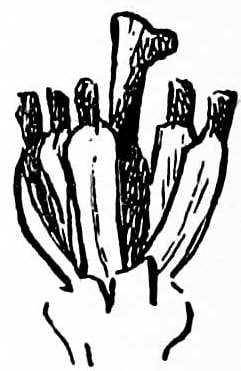

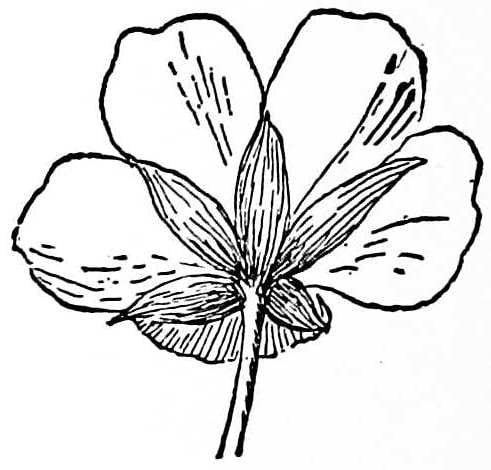

The general building plan of the violet is the old one of calyx, corolla, stamens, pistil. But the leaves of this calyx are put together in a curious, irregular fashion; and the different leaves of the corolla are not of the same shape and size as in the cherry blossom. Then the five stamens of the violet are usually joined about the stalk of the pistil in a way that is quite confusing, unless you know enough to pick them apart with a pin, when they look like this picture you see above, to the right.

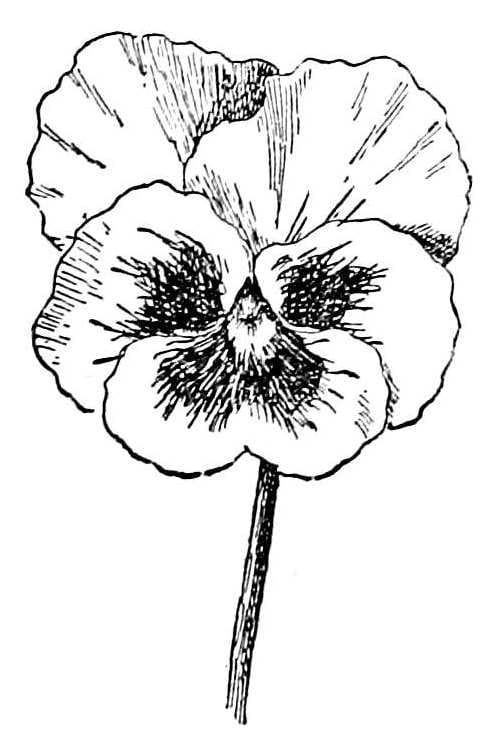

The garden pansy is cousin to the violet. You notice at once that it uses just the same building plan.

The wild geranium is put together almost as simply as the cherry blossom.

A more beautiful flower than the columbine it would be difficult to find. Its graceful hanging head and brilliant coloring make it a delight to the passer-by.

It has not the fragrance of some other flowers, but for this there is a good reason.

The columbine is so brightly colored that the nectar-hunting bee can see it from a great distance.

It is only when a blossom is so small and faintly colored as to be unlikely to attract the eye, that it needs to make its presence known in some other way than by wearing gay clothes. By giving out fragrance it notifies the bee that material for honey making is on hand.

So you see that a pale little flower with a strong fragrance is just as able to attract the bee’s attention as is a big flower with its bright flower handkerchiefs. A big flower with bright flower handkerchiefs does not need to attract the bee by its perfume.

Perhaps you will be somewhat surprised to learn that this columbine uses the old plan, calyx, corolla, stamens, pistil.

In the columbine the calyx as well as the corolla is brightly and beautifully colored, and only the botanist can tell which is which. In this way many flowers confuse one who is only beginning their study. So you must try to be patient when you come across a flower whose coloring and shape make it impossible for you to say what is calyx and what is corolla. You should turn both over into the one division of flower leaves, and when older you may be able to master the difficulty.

The pretty fringed polygala is one of these confusing flower. You find it in the May woods. Its discovery is such a delight, that one is not apt to make himself unhappy because he cannot make out all its parts.

The jewelweed, the plant which blossoms down by the brook in August, is another of these puzzling blossoms.