It would be quite a simple matter to interest you children in plants and their lives, if always it were possible to talk only about the things which you can see with your own unaided eyes.

I think a bright child sees better than many a grown person, and I think that it is easier to interest him in what he sees.

And then plants in themselves are so interesting and surprising, that one must be stupid indeed if he or she finds it impossible to take pleasure in watching their ways.

But about these plants there are many things which you cannot see without the help of a microscope, and these things it is difficult to describe in simple words. Yet it is necessary to learn about them if you wish really to feel at home in this beautiful world of plants.

After all, whatever is worth having is worth taking some trouble for; and nothing worth having can be had without trouble. So I hope when you children come to parts of this book that seem at first a little dull, you will say to yourselves, “Well, if we wish really to know plants, to be able to tell their names, to understand their habits, we must try to be a little patient when we come to the things that are difficult.”

For even in your games you boys have to use some patience; and you are quite willing to run the risk of being hurt for the sake of a little fun.

And you girls will take no end of trouble if you happen to be sewing for your dolls, or playing at cooking over the kitchen stove, or doing something to which you give the name “play” instead of “work.”

I only ask for just as much patience in your study of plants; and I think I can safely promise you that plants will prove delightful playthings long after you have put aside the games which please you now.

So we must begin to talk about some of the things which you are not likely to see now with your own eyes, but which, when possible, I will show you by means of pictures, and which, when you are older, some of you may see with the help of a microscope.

Every living thing is made up of one or more little objects called “cells.”

Usually a cell may be likened to a tiny bag which holds a bit of that material which is the most wonderful thing in the whole world, for this is the material which has life.

Occasionally a cell is nothing but a naked bit of this wonderful substance, for it is not always held in a tiny bag.

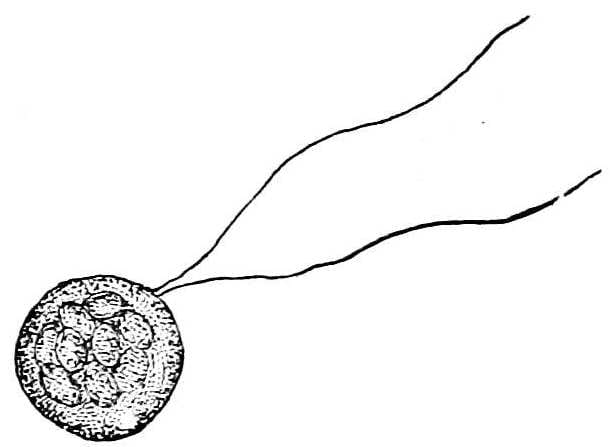

This picture shows you a naked plant cell, much magnified, that swims about in the water by means of the two long hairs which grow from one end of the speck of life-giving material.

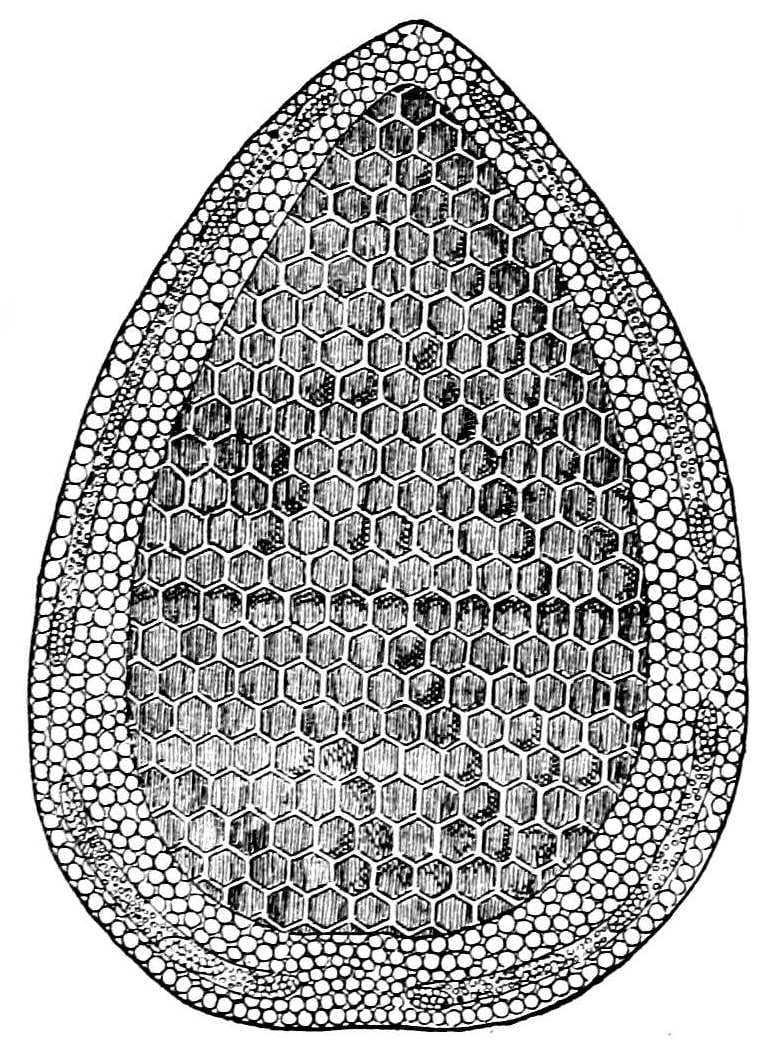

The next picture shows you a seed cut across, and so magnified that you can see plainly its many cells.

In the middle portion of the seed the cells are six-sided, and laid against one another in an orderly and beautiful fashion, while the outer ones are mostly round.

All animals, we ourselves, all plants, began life as a single cell.

Sometimes a cell will spend its life alone. When the time comes for it to add to the life of the world, it divides into two or more “daughter cells,” as they are called. These break away from one another, and in like manner divide again.

But usually the single cell which marks the beginning of a new life adds to itself other cells; that is, the different cells do not break away from one another, but all cling together, and so build up the perfect plant or animal.

By just such additions the greatest tree in the forest grew from a single tiny cell.

By just such additions you children have grown to be what you are, and in the same way you will continue to grow.

Every living thing must eat and breathe, and so all living cells must have food and air. These they take in through their delicate cell walls. The power to do this comes from the bit of living substance which lies within these walls.

This strange, wonderful material within the little cell is what is alive in every man and woman, in every boy and girl, in every living thing, whether plant or animal.

We know this much about it, and not the wisest man that ever lived knows much more.

For though the wise men know just what things go to make up this material, and though they themselves can put together these same things, they can no more make life, or understand the making of it, than can you or I.

But when we get a good hold of the idea that this material is contained in all living things, then we begin to feel this; we begin to feel that men and women, boys and girls, big animals and little insects, trees and flowers, wayside weeds and grasses, the ferns and rushes of the forest, the gray lichens of the cliffs and fences, the seaweeds that sway in the green rock pools, and living things so tiny that our eyes must fail to see them,—that all these are bound into one by the tie of that strange and wonderful thing called life; that they are all different expressions of one mysterious, magnificent idea.

While writing that last sentence, I almost forgot that I was writing for boys and girls, or indeed for any one but myself; and I am afraid that perhaps you have very little idea of what I am talking about.

But I will not cross it out. Why not, do you suppose?

Because I feel almost sure that here and there among you is a girl or boy who will get just a little glimmering idea of what I mean; and perhaps as the years go by, that glimmer will change into a light so bright and clear as to become a help in dark places.

But the thought that I hope each one of you will carry home is this,—that because this strange something found in your body is also found in every other living thing, you may learn to feel that you are in a way a sister or brother, not only to all other boys and girls, but to all the animals and to every plant about you.