But before we finished talking about roots we were led away by underground stems. This does not matter much, however, for these underground stems are still called roots by many people.

Just as stems sometimes grow under ground, roots sometimes grow above ground.

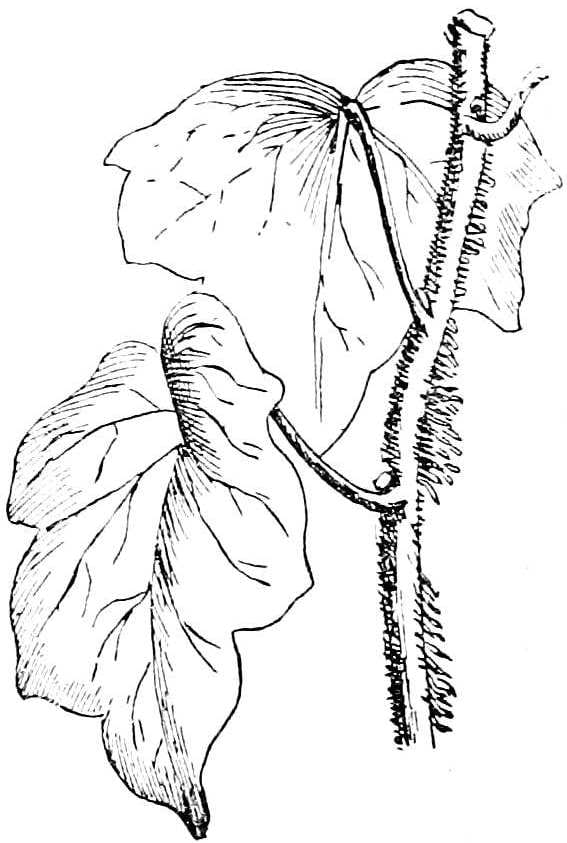

Many of you know the English ivy. This is one of the few plants which city children know quite as well as, if not better than, country children; for in our cities it nearly covers the walls of the churches. In England it grows so luxuriantly that some of the old buildings are hidden beneath masses of its dark leaves.

This ivy plant springs from a root in the earth; but as it makes its way upward, it clings to the stone wall by means of the many air roots which it puts forth.

Our own poison ivy is another plant with air roots used for climbing purposes. Often these roots make its stem look as though it were covered with a heavy growth of coarse hair.

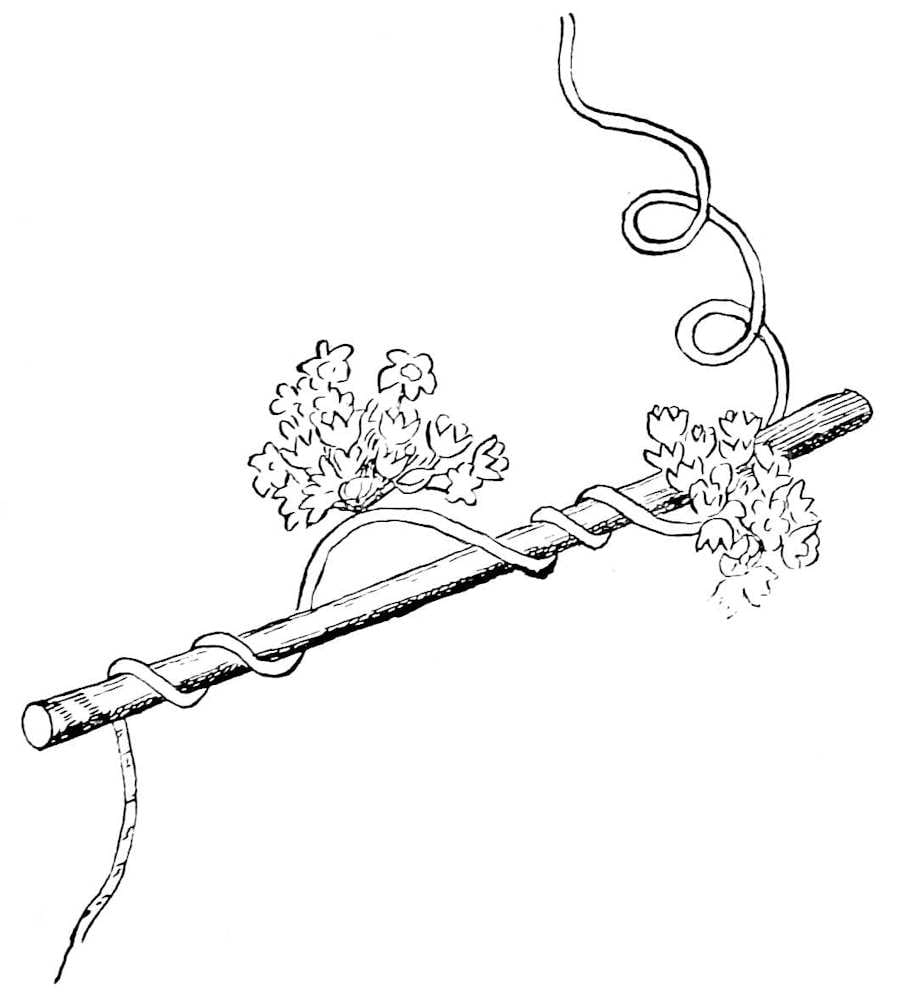

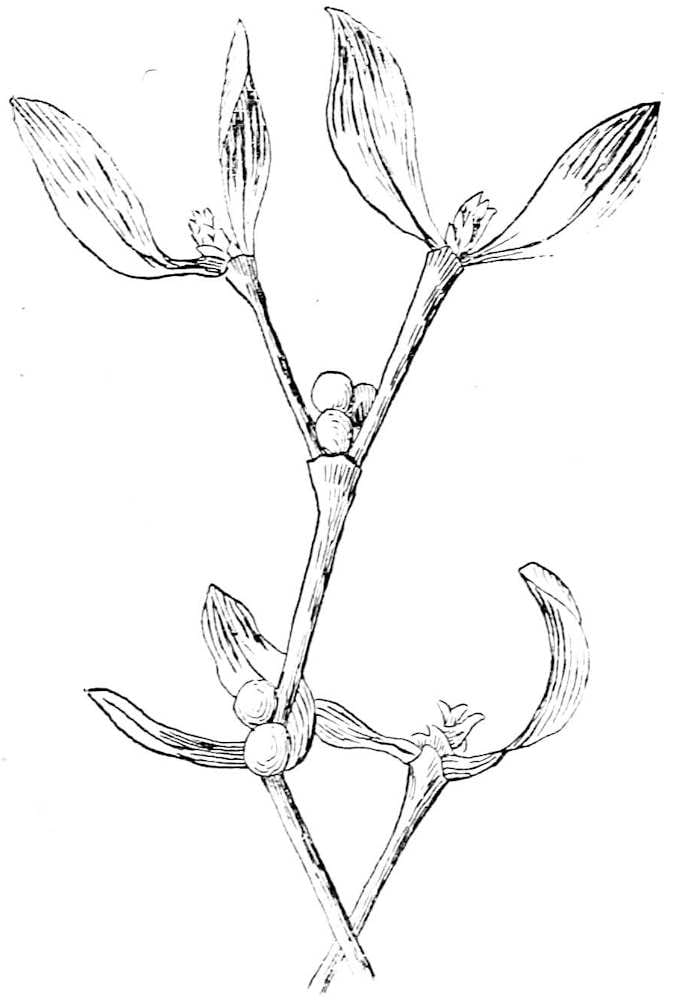

There are some plants which take root in the branches of trees. Many members of the Orchid family perch themselves aloft in this fashion. But the roots which provide these plants with the greater part of their nourishment are those which hang loosely in the air. One of these orchids you see in the picture. It is found in warm countries. The orchids of our part of the world grow in the ground in everyday fashion, and look much like other plants.

These hanging roots which you see in the picture are covered with a sponge-like material, by means of which they suck in from the air water and gases.

In summer, while hunting berries or wild flowers by the stream that runs through the pasture, you have noticed that certain plants seemed to be caught in a tangle of golden threads. If you stopped to look at this tangle, you found little clusters of white flowers scattered along the thread-like stems; then, to your surprise, you discovered that nowhere was this odd-looking stem fastened to the ground.

It began and ended high above the earth, among the plants which crowded along the brook’s edge.

Perhaps you broke off one of these plants about which the golden threads were twining. If so, you found that these threads were fastened firmly to the plant by means of little roots which grew into its stem, just as ordinary roots grow into the earth.

This strange plant is called the “dodder.” When it was still a baby plant, it lay within its seed upon the ground, just like other baby plants; and when it burst its seed shell, like other plants it sent its roots down into the earth.

But unlike any other plant I know of, it did not send up into the air any seed leaves. The dodder never bears a leaf.

It sent upward a slender golden stem. Soon the stem began to sweep slowly through the air in circles, as if searching for something. Its movements were like those of a blind man who is feeling with his hands for support. And this is just what the plant was doing: it was feeling for support. And it kept up its slow motion till it found the plant which was fitted to give it what it needed.

Having made this discovery, it put out a little root. This root it sent into the juicy stem of its new-found support. And thereafter, from its private store, the unfortunate plant which had been chosen as the dodder’s victim was obliged to give food and drink to its greedy visitor.

And now what does this dodder do, do you suppose? Perhaps you think that at least it has the grace to do a little something for a living, and that it makes its earth root supply it with part of its food.

Nothing of the sort. Once it finds itself firmly rooted in the stem of its victim, it begins to grow vigorously. With every few inches of its growth it sends new roots deep into this stem. And when it feels quite at home, and perfectly sure of its board, it begins to wither away below, where it is joined to its earth root. Soon it breaks off entirely from this, and draws every bit of its nourishment from the plant or plants in which it is rooted.

Now stop a moment and think of the almost wicked intelligence this plant has seemed to show,—how it keeps its hold of the earth till its stem has found the plant which will be compelled to feed it, and how it gives up all pretense of self-support, once it has captured its prey.

You have heard of men and women who do this sort of thing,—who shirk all trouble, and try to live on the work of others; and I fear you know some boys and girls who are not altogether unlike the dodder,—boys and girls who never take any pains if they can possibly help it, who try to have all of the fun and none of the work; but did you ever suppose you would come across a plant that would conduct itself in such a fashion?

Of course, when the dodder happens to fasten itself upon some wild plant, little harm is done. But unfortunately it is very partial to plants that are useful to men, and then we must look upon it as an enemy.

Linen is made from the flax plant, and this flax plant is one of the favorite victims of the dodder. Sometimes it will attack and starve to death whole fields of flax.

But do not let us forget that we happen to be talking about the dodder because it is one of the plants which put out roots above ground.

There is one plant which many of you have seen, that never, at any time of its life, is rooted in the earth, but which feeds always upon the branches of the trees in which it lives.

This plant is one of which perhaps you hear and see a good deal at Christmas time. It is an old English custom, at this season, to hang somewhere about the house a mistletoe bough (for the mistletoe is the plant I mean) with the understanding that one is free to steal a kiss from any maiden caught beneath it. And as mistletoe boughs are sold on our street corners and in our shops at Christmas, there has been no difficulty in bringing one to school to-day.

The greenish mistletoe berries are eaten by birds. Often their seeds are dropped by these birds upon the branches of trees. There they hold fast by means of the sticky material with which they are covered. Soon they send out roots which pierce the bark, and, like the roots of the dodder, suck up the juices of the tree, and supply the plant with nourishment.

Then there are water roots as well as earth roots. Some of these water roots are put forth by plants which are nowhere attached to the earth. These are plants which you would not be likely to know about. One of them, the duckweed, is very common in ponds; but it is so tiny that when you have seen a quantity of these duckweeds, perhaps you have never supposed them to be true plants, but rather a green scum floating on the top of the water.

But the duckweed is truly a plant. It has both flower and fruit, although without a distinct stem and leaves; and it sends down into the water its long, hanging roots, which yet do not reach the ground.

There are other plants which have at the same time underground roots and water roots.

Rooted in the earth on the borders of a stream sometimes you see a willow tree which has put out above-ground roots. These hang over the bank and float in the water, apparently with great enjoyment; for roots not only seem to seek the water, but to like it, and to flourish in it.

If you break off at the ground one of your bean plants, and place the slip in a glass of water, you will see for yourselves how readily it sends out new roots.

I have read of a village tree the roots of which had made their way into a water pipe. Here they grew so abundantly that soon the pipe was entirely choked. This rapid, luxuriant growth was supposed to have been caused by the water within the pipe.

So you see there are underground roots and above-ground roots and water roots. Usually, as you know, the underground roots get their food from the earth; but sometimes, as with the Indian pipe, they feed on dead plants, and sometimes, as with the yellow false foxglove, on other living roots.