The winter was a wretched one. There were days on which Sara tramped through snow when she went on her errands; there were worse days when the snow melted and combined itself with mud to form slush; there were others when the fog was so thick that the lamps in the street were lighted all day and London looked as it had looked the afternoon, several years ago, when the cab had driven through the thoroughfares with Sara tucked up on its seat, leaning against her father’s shoulder. On such days the windows of the house of the Large Family always looked delightfully cozy and alluring, and the study in which the Indian gentleman sat glowed with warmth and rich color. But the attic was dismal beyond words. There were no longer sunsets or sunrises to look at, and scarcely ever any stars, it seemed to Sara. The clouds hung low over the skylight and were either gray or mud-color, or dropping heavy rain. At four o’clock in the afternoon, even when there was no special fog, the daylight was at an end. If it was necessary to go to her attic for anything, Sara was obliged to light a candle. The women in the kitchen were depressed, and that made them more ill-tempered than ever. Becky was driven like a little slave.

“‘Twarn’t for you, miss,” she said hoarsely to Sara one night when she had crept into the attic—”‘twarn’t for you, an’ the Bastille, an’ bein’ the prisoner in the next cell, I should die. That there does seem real now, doesn’t it? The missus is more like the head jailer every day she lives. I can jest see them big keys you say she carries. The cook she’s like one of the under-jailers. Tell me some more, please, miss—tell me about the subt’ranean passage we’ve dug under the walls.”

“I’ll tell you something warmer,” shivered Sara. “Get your coverlet and wrap it round you, and I’ll get mine, and we will huddle close together on the bed, and I’ll tell you about the tropical forest where the Indian gentleman’s monkey used to live. When I see him sitting on the table near the window and looking out into the street with that mournful expression, I always feel sure he is thinking about the tropical forest where he used to swing by his tail from coconut trees. I wonder who caught him, and if he left a family behind who had depended on him for coconuts.”

“That is warmer, miss,” said Becky, gratefully; “but, someways, even the Bastille is sort of heatin’ when you gets to tellin’ about it.”

“That is because it makes you think of something else,” said Sara, wrapping the coverlet round her until only her small dark face was to be seen looking out of it. “I’ve noticed this. What you have to do with your mind, when your body is miserable, is to make it think of something else.”

“Can you do it, miss?” faltered Becky, regarding her with admiring eyes.

Sara knitted her brows a moment.

“Sometimes I can and sometimes I can’t,” she said stoutly. “But when I CAN I’m all right. And what I believe is that we always could—if we practiced enough. I’ve been practicing a good deal lately, and it’s beginning to be easier than it used to be. When things are horrible—just horrible—I think as hard as ever I can of being a princess. I say to myself, ‘I am a princess, and I am a fairy one, and because I am a fairy nothing can hurt me or make me uncomfortable.’ You don’t know how it makes you forget”—with a laugh.

She had many opportunities of making her mind think of something else, and many opportunities of proving to herself whether or not she was a princess. But one of the strongest tests she was ever put to came on a certain dreadful day which, she often thought afterward, would never quite fade out of her memory even in the years to come.

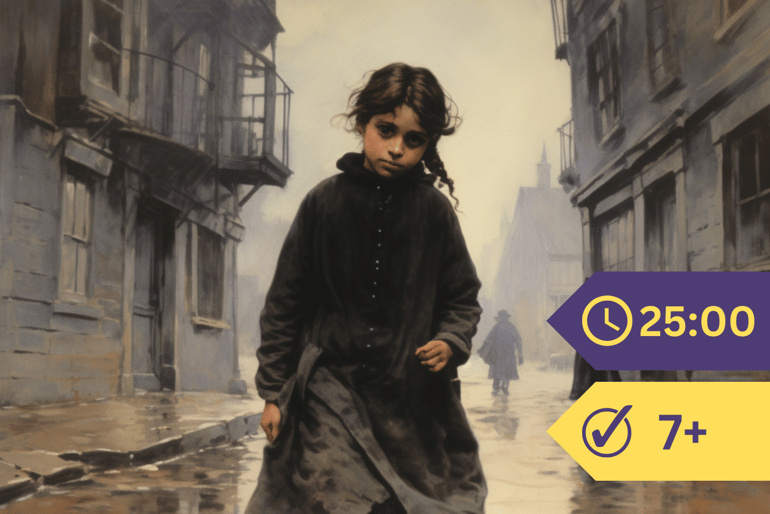

For several days it had rained continuously; the streets were chilly and sloppy and full of dreary, cold mist; there was mud everywhere—sticky London mud—and over everything the pall of drizzle and fog. Of course there were several long and tiresome errands to be done—there always were on days like this—and Sara was sent out again and again, until her shabby clothes were damp through. The absurd old feathers on her forlorn hat were more draggled and absurd than ever, and her downtrodden shoes were so wet that they could not hold any more water. Added to this, she had been deprived of her dinner, because Miss Minchin had chosen to punish her. She was so cold and hungry and tired that her face began to have a pinched look, and now and then some kind-hearted person passing her in the street glanced at her with sudden sympathy. But she did not know that. She hurried on, trying to make her mind think of something else. It was really very necessary. Her way of doing it was to “pretend” and “suppose” with all the strength that was left in her. But really this time it was harder than she had ever found it, and once or twice she thought it almost made her more cold and hungry instead of less so. But she persevered obstinately, and as the muddy water squelched through her broken shoes and the wind seemed trying to drag her thin jacket from her, she talked to herself as she walked, though she did not speak aloud or even move her lips.

“Suppose I had dry clothes on,” she thought. “Suppose I had good shoes and a long, thick coat and merino stockings and a whole umbrella. And suppose—suppose—just when I was near a baker’s where they sold hot buns, I should find sixpence—which belonged to nobody. SUPPOSE if I did, I should go into the shop and buy six of the hottest buns and eat them all without stopping.”

Some very odd things happen in this world sometimes.

It certainly was an odd thing that happened to Sara. She had to cross the street just when she was saying this to herself. The mud was dreadful—she almost had to wade. She picked her way as carefully as she could, but she could not save herself much; only, in picking her way, she had to look down at her feet and the mud, and in looking down—just as she reached the pavement—she saw something shining in the gutter. It was actually a piece of silver—a tiny piece trodden upon by many feet, but still with spirit enough left to shine a little. Not quite a sixpence, but the next thing to it—a fourpenny piece.

In one second it was in her cold little red-and-blue hand.

“Oh,” she gasped, “it is true! It is true!”

And then, if you will believe me, she looked straight at the shop directly facing her. And it was a baker’s shop, and a cheerful, stout, motherly woman with rosy cheeks was putting into the window a tray of delicious newly baked hot buns, fresh from the oven—large, plump, shiny buns, with currants in them.

It almost made Sara feel faint for a few seconds—the shock, and the sight of the buns, and the delightful odors of warm bread floating up through the baker’s cellar window.

She knew she need not hesitate to use the little piece of money. It had evidently been lying in the mud for some time, and its owner was completely lost in the stream of passing people who crowded and jostled each other all day long.

“But I’ll go and ask the baker woman if she has lost anything,” she said to herself, rather faintly. So she crossed the pavement and put her wet foot on the step. As she did so she saw something that made her stop.

It was a little figure more forlorn even than herself—a little figure which was not much more than a bundle of rags, from which small, bare, red muddy feet peeped out, only because the rags with which their owner was trying to cover them were not long enough. Above the rags appeared a shock head of tangled hair, and a dirty face with big, hollow, hungry eyes.

Sara knew they were hungry eyes the moment she saw them, and she felt a sudden sympathy.

“This,” she said to herself, with a little sigh, “is one of the populace—and she is hungrier than I am.”

The child—this “one of the populace”—stared up at Sara, and shuffled herself aside a little, so as to give her room to pass. She was used to being made to give room to everybody. She knew that if a policeman chanced to see her he would tell her to “move on.”

Sara clutched her little fourpenny piece and hesitated for a few seconds. Then she spoke to her.

“Are you hungry?” she asked.

The child shuffled herself and her rags a little more.

“Ain’t I jist?” she said in a hoarse voice. “Jist ain’t I?”

“Haven’t you had any dinner?” said Sara.

“No dinner,” more hoarsely still and with more shuffling. “Nor yet no bre’fast—nor yet no supper. No nothin’.

“Since when?” asked Sara.

“Dunno. Never got nothin’ today—nowhere. I’ve axed an’ axed.”

Just to look at her made Sara more hungry and faint. But those queer little thoughts were at work in her brain, and she was talking to herself, though she was sick at heart.

“If I’m a princess,” she was saying, “if I’m a princess—when they were poor and driven from their thrones—they always shared—with the populace—if they met one poorer and hungrier than themselves. They always shared. Buns are a penny each. If it had been sixpence I could have eaten six. It won’t be enough for either of us. But it will be better than nothing.”

“Wait a minute,” she said to the beggar child.

She went into the shop. It was warm and smelled deliciously. The woman was just going to put some more hot buns into the window.

“If you please,” said Sara, “have you lost fourpence—a silver fourpence?” And she held the forlorn little piece of money out to her.

The woman looked at it and then at her—at her intense little face and draggled, once fine clothes.

“Bless us, no,” she answered. “Did you find it?”

“Yes,” said Sara. “In the gutter.”

“Keep it, then,” said the woman. “It may have been there for a week, and goodness knows who lost it. YOU could never find out.”

“I know that,” said Sara, “but I thought I would ask you.”

“Not many would,” said the woman, looking puzzled and interested and good-natured all at once.

“Do you want to buy something?” she added, as she saw Sara glance at the buns.

“Four buns, if you please,” said Sara. “Those at a penny each.”

The woman went to the window and put some in a paper bag.

Sara noticed that she put in six.

“I said four, if you please,” she explained. “I have only fourpence.”

“I’ll throw in two for makeweight,” said the woman with her good-natured look. “I dare say you can eat them sometime. Aren’t you hungry?”

A mist rose before Sara’s eyes.

“Yes,” she answered. “I am very hungry, and I am much obliged to you for your kindness; and”—she was going to add—”there is a child outside who is hungrier than I am.” But just at that moment two or three customers came in at once, and each one seemed in a hurry, so she could only thank the woman again and go out.

The beggar girl was still huddled up in the corner of the step. She looked frightful in her wet and dirty rags. She was staring straight before her with a stupid look of suffering, and Sara saw her suddenly draw the back of her roughened black hand across her eyes to rub away the tears which seemed to have surprised her by forcing their way from under her lids. She was muttering to herself.

Sara opened the paper bag and took out one of the hot buns, which had already warmed her own cold hands a little.

“See,” she said, putting the bun in the ragged lap, “this is nice and hot. Eat it, and you will not feel so hungry.”

The child started and stared up at her, as if such sudden, amazing good luck almost frightened her; then she snatched up the bun and began to cram it into her mouth with great wolfish bites.

“Oh, my! Oh, my!” Sara heard her say hoarsely, in wild delight. “OH my!”

Sara took out three more buns and put them down.

The sound in the hoarse, ravenous voice was awful.

“She is hungrier than I am,” she said to herself. “She’s starving.” But her hand trembled when she put down the fourth bun. “I’m not starving,” she said—and she put down the fifth.

The little ravening London savage was still snatching and devouring when she turned away. She was too ravenous to give any thanks, even if she had ever been taught politeness—which she had not. She was only a poor little wild animal.

“Good-bye,” said Sara.

When she reached the other side of the street she looked back. The child had a bun in each hand and had stopped in the middle of a bite to watch her. Sara gave her a little nod, and the child, after another stare—a curious lingering stare—jerked her shaggy head in response, and until Sara was out of sight she did not take another bite or even finish the one she had begun.

At that moment the baker-woman looked out of her shop window.

“Well, I never!” she exclaimed. “If that young un hasn’t given her buns to a beggar child! It wasn’t because she didn’t want them, either. Well, well, she looked hungry enough. I’d give something to know what she did it for.”

She stood behind her window for a few moments and pondered. Then her curiosity got the better of her. She went to the door and spoke to the beggar child.

“Who gave you those buns?” she asked her. The child nodded her head toward Sara’s vanishing figure.

“What did she say?” inquired the woman.

“Axed me if I was ‘ungry,” replied the hoarse voice.

“What did you say?”

“Said I was jist.”

“And then she came in and got the buns, and gave them to you, did she?”

The child nodded.

“How many?”

“Five.”

The woman thought it over.

“Left just one for herself,” she said in a low voice. “And she could have eaten the whole six—I saw it in her eyes.”

She looked after the little draggled far-away figure and felt more disturbed in her usually comfortable mind than she had felt for many a day.

“I wish she hadn’t gone so quick,” she said. “I’m blest if she shouldn’t have had a dozen.” Then she turned to the child.

“Are you hungry yet?” she said.

“I’m allus hungry,” was the answer, “but ‘t ain’t as bad as it was.”

“Come in here,” said the woman, and she held open the shop door.

The child got up and shuffled in. To be invited into a warm place full of bread seemed an incredible thing. She did not know what was going to happen. She did not care, even.

“Get yourself warm,” said the woman, pointing to a fire in the tiny back room. “And look here; when you are hard up for a bit of bread, you can come in here and ask for it. I’m blest if I won’t give it to you for that young one’s sake.”

* * *

Sara found some comfort in her remaining bun. At all events, it was very hot, and it was better than nothing. As she walked along she broke off small pieces and ate them slowly to make them last longer.

“Suppose it was a magic bun,” she said, “and a bite was as much as a whole dinner. I should be overeating myself if I went on like this.”

It was dark when she reached the square where the Select Seminary was situated. The lights in the houses were all lighted. The blinds were not yet drawn in the windows of the room where she nearly always caught glimpses of members of the Large Family. Frequently at this hour she could see the gentleman she called Mr. Montmorency sitting in a big chair, with a small swarm round him, talking, laughing, perching on the arms of his seat or on his knees or leaning against them. This evening the swarm was about him, but he was not seated. On the contrary, there was a good deal of excitement going on. It was evident that a journey was to be taken, and it was Mr. Montmorency who was to take it. A brougham stood before the door, and a big portmanteau had been strapped upon it. The children were dancing about, chattering and hanging on to their father. The pretty rosy mother was standing near him, talking as if she was asking final questions. Sara paused a moment to see the little ones lifted up and kissed and the bigger ones bent over and kissed also.

“I wonder if he will stay away long,” she thought. “The portmanteau is rather big. Oh, dear, how they will miss him! I shall miss him myself—even though he doesn’t know I am alive.”

When the door opened she moved away—remembering the sixpence—but she saw the traveler come out and stand against the background of the warmly-lighted hall, the older children still hovering about him.

“Will Moscow be covered with snow?” said the little girl Janet. “Will there be ice everywhere?”

“Shall you drive in a drosky?” cried another. “Shall you see the Czar?”

“I will write and tell you all about it,” he answered, laughing. “And I will send you pictures of muzhiks and things. Run into the house. It is a hideous damp night. I would rather stay with you than go to Moscow. Good night! Good night, duckies! God bless you!” And he ran down the steps and jumped into the brougham.

“If you find the little girl, give her our love,” shouted Guy Clarence, jumping up and down on the door mat.

Then they went in and shut the door.

“Did you see,” said Janet to Nora, as they went back to the room—”the little-girl-who-is-not-a-beggar was passing? She looked all cold and wet, and I saw her turn her head over her shoulder and look at us. Mamma says her clothes always look as if they had been given her by someone who was quite rich—someone who only let her have them because they were too shabby to wear. The people at the school always send her out on errands on the horridest days and nights there are.”

Sara crossed the square to Miss Minchin’s area steps, feeling faint and shaky.

“I wonder who the little girl is,” she thought—”the little girl he is going to look for.”

And she went down the area steps, lugging her basket and finding it very heavy indeed, as the father of the Large Family drove quickly on his way to the station to take the train which was to carry him to Moscow, where he was to make his best efforts to search for the lost little daughter of Captain Crewe.