They were proceeding so easily and comfortably on their way to Mount Munch that Woot said in a serious tone of voice:

“I’m afraid something is going to happen.”

“Why?” asked Polychrome, dancing around the group of travelers.

“Because,” said the boy, thoughtfully, “I’ve noticed that when we have the least reason for getting into trouble, something is sure to go wrong. Just now the weather is delightful; the grass is beautifully blue and quite soft to our feet; the mountain we are seeking shows clearly in the distance and there is no reason anything should happen to delay us in getting there. Our troubles all seem to be over, and—well, that’s why I’m afraid,” he added, with a sigh.

“Dear me!” remarked the Scarecrow, “what unhappy thoughts you have, to be sure. This is proof that born brains cannot equal manufactured brains, for my brains dwell only on facts and never borrow trouble. When there is occasion for my brains to think, they think, but I would be ashamed of my brains if they kept shooting out thoughts that were merely fears and imaginings, such as do no good, but are likely to do harm.”

“For my part,” said the Tin Woodman, “I do not think at all, but allow my velvet heart to guide me at all times.”

“The tinsmith filled my hollow head with scraps and clippings of tin,” said the Soldier, “and he told me they would do nicely for brains, but when I begin to think, the tin scraps rattle around and get so mixed that I’m soon bewildered. So I try not to think. My tin heart is almost as useless to me, for it is hard and cold, so I’m sure the red velvet heart of my friend Nick Chopper is a better guide.”

“Thoughtless people are not unusual,” observed the Scarecrow, “but I consider them more fortunate than those who have useless or wicked thoughts and do not try to curb them. Your oil can, friend Woodman, is filled with oil, but you only apply the oil to your joints, drop by drop, as you need it, and do not keep spilling it where it will do no good. Thoughts should be restrained in the same way as your oil, and only applied when necessary, and for a good purpose. If used carefully, thoughts are good things to have.”

Polychrome laughed at him, for the Rainbow’s Daughter knew more about thoughts than the Scarecrow did. But the others were solemn, feeling they had been rebuked, and tramped on in silence.

Suddenly Woot, who was in the lead, looked around and found that all his comrades had mysteriously disappeared. But where could they have gone to? The broad plain was all about him and there were neither trees nor bushes that could hide even a rabbit, nor any hole for one to fall into. Yet there he stood, alone.

Surprise had caused him to halt, and with a thoughtful and puzzled expression on his face he looked down at his feet. It startled him anew to discover that he had no feet. He reached out his hands, but he could not see them. He could feel his hands and arms and body; he stamped his feet on the grass and knew they were there, but in some strange way they had become invisible.

While Woot stood, wondering, a crash of metal sounded in his ears and he heard two heavy bodies tumble to the earth just beside him.

“Good gracious!” exclaimed the voice of the Tin Woodman.

“Mercy me!” cried the voice of the Tin Soldier.

“Why didn’t you look where you were going?” asked the Tin Woodman reproachfully.

“I did, but I couldn’t see you,” said the Tin Soldier. “Something has happened to my tin eyes. I can’t see you, even now, nor can I see anyone else!”

“It’s the same way with me,” admitted the Tin Woodman.

Woot couldn’t see either of them, although he heard them plainly, and just then something smashed against him unexpectedly and knocked him over; but it was only the straw-stuffed body of the Scarecrow that fell upon him and while he could not see the Scarecrow he managed to push him off and rose to his feet just as Polychrome whirled against him and made him tumble again.

Sitting upon the ground, the boy asked:

“Can you see us, Poly?”

“No, indeed,” answered the Rainbow’s Daughter; “we’ve all become invisible.”

“How did it happen, do you suppose?” inquired the Scarecrow, lying where he had fallen.

“We have met with no enemy,” answered Polychrome, “so it must be that this part of the country has the magic quality of making people invisible—even fairies falling under the charm. We can see the grass, and the flowers, and the stretch of plain before us, and we can still see Mount Munch in the distance; but we cannot see ourselves or one another.”

“Well, what are we to do about it?” demanded Woot.

“I think this magic affects only a small part of the plain,” replied Polychrome; “perhaps there is only a streak of the country where an enchantment makes people become invisible. So, if we get together and hold hands, we can travel toward Mount Munch until the enchanted streak is passed.”

“All right,” said Woot, jumping up, “give me your hand, Polychrome. Where are you?”

“Here,” she answered. “Whistle, Woot, and keep whistling until I come to you.”

So Woot whistled, and presently Polychrome found him and grasped his hand.

“Someone must help me up,” said the Scarecrow, lying near them; so they found the straw man and sat him upon his feet, after which he held fast to Polychrome’s other hand.

Nick Chopper and the Tin Soldier had managed to scramble up without assistance, but it was awkward for them and the Tin Woodman said:

“I don’t seem to stand straight, somehow. But my joints all work, so I guess I can walk.”

Guided by his voice, they reached his side, where Woot grasped his tin fingers so they might keep together.

The Tin Soldier was standing near by and the Scarecrow soon touched him and took hold of his arm.

“I hope you’re not wobbly,” said the straw man, “for if two of us walk unsteadily we will be sure to fall.”

“I’m not wobbly,” the Tin Soldier assured him, “but I’m certain that one of my legs is shorter than the other. I can’t see it, to tell what’s gone wrong, but I’ll limp on with the rest of you until we are out of this enchanted territory.”

They now formed a line, holding hands, and turning their faces toward Mount Munch resumed their journey. They had not gone far, however, when a terrible growl saluted their ears. The sound seemed to come from a place just in front of them, so they halted abruptly and remained silent, listening with all their ears.

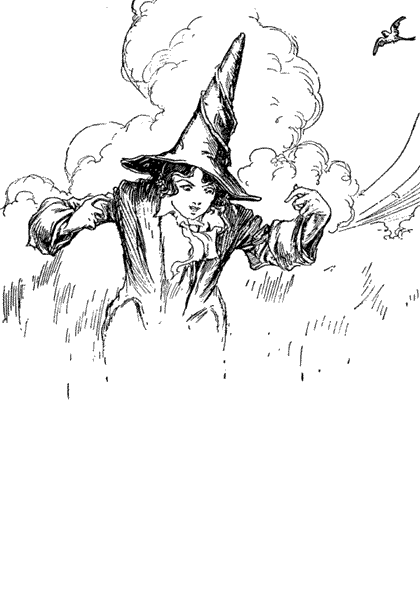

“I smell straw!” cried a hoarse, harsh voice, with more growls and snarls. “I smell straw, and I’m a Hip-po-gy-raf who loves straw and eats all he can find. I want to eat this straw! Where is it? Where is it?”

The Scarecrow, hearing this, trembled but kept silent. All the others were silent, too, hoping that the invisible beast would be unable to find them. But the creature sniffed the odor of the straw and drew nearer and nearer to them until he reached the Tin Woodman, on one end of the line. It was a big beast and it smelled of the Tin Woodman and grated two rows of enormous teeth against the Emperor’s tin body.

“Bah! that’s not straw,” said the harsh voice, and the beast advanced along the line to Woot.

“Meat! Pooh, you’re no good! I can’t eat meat,” grumbled the beast, and passed on to Polychrome.

“Sweetmeats and perfume—cobwebs and dew! Nothing to eat in a fairy like you,” said the creature.

Now, the Scarecrow was next to Polychrome in the line, and he realized if the beast devoured his straw he would be helpless for a long time, because the last farmhouse was far behind them and only grass covered the vast expanse of plain. So in his fright he let go of Polychrome’s hand and put the hand of the Tin Soldier in that of the Rainbow’s Daughter. Then he slipped back of the line and went to the other end, where he silently seized the Tin Woodman’s hand.

Meantime, the beast had smelled the Tin Soldier and found he was the last of the line.

“That’s funny!” growled the Hip-po-gy-raf; “I can smell straw, but I can’t find it. Well, it’s here, somewhere, and I must hunt around until I do find it, for I’m hungry.”

His voice was now at the left of them, so they started on, hoping to avoid him, and traveled as fast as they could in the direction of Mount Munch.

“I don’t like this invisible country,” said Woot with a shudder. “We can’t tell how many dreadful, invisible beasts are roaming around us, or what danger we’ll come to next.”

“Quit thinking about danger, please,” said the Scarecrow, warningly.

“Why?” asked the boy.

“If you think of some dreadful thing, it’s liable to happen, but if you don’t think of it, and no one else thinks of it, it just can’t happen. Do you see?”

“No,” answered Woot. “I won’t be able to see much of anything until we escape from this enchantment.”

But they got out of the invisible strip of country as suddenly as they had entered it, and the instant they got out they stopped short, for just before them was a deep ditch, running at right angles as far as their eyes could see and stopping all further progress toward Mount Munch.

“It’s not so very wide,” said Woot, “but I’m sure none of us can jump across it.”

Polychrome began to laugh, and the Scarecrow said: “What’s the matter?”

“Look at the tin men!” she said, with another burst of merry laughter.

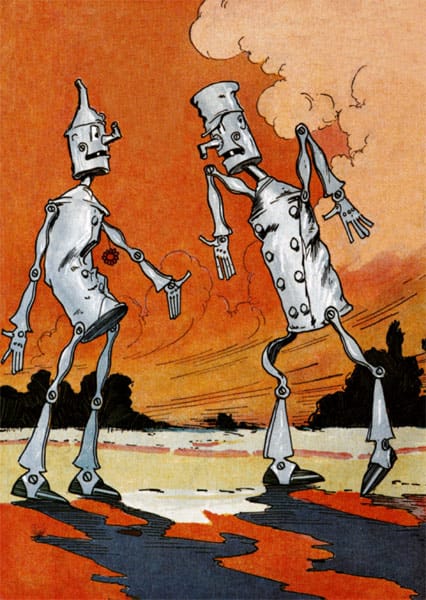

Woot and the Scarecrow looked, and the tin men looked at themselves.

“It was the collision,” said the Tin Woodman regretfully. “I knew something was wrong with me, and now I can see that my side is dented in so that I lean over toward the left. It was the Soldier’s fault; he shouldn’t have been so careless.”

“It is your fault that my right leg is bent, making it shorter than the other, so that I limp badly,” retorted the Soldier. “You shouldn’t have stood where I was walking.”

“You shouldn’t have walked where I was standing,” replied the Tin Woodman.

It was almost a quarrel, so Polychrome said soothingly:

“Never mind, friends; as soon as we have time I am sure we can straighten the Soldier’s leg and get the dent out of the Woodman’s body. The Scarecrow needs patting into shape, too, for he had a bad tumble, but our first task is to get over this ditch.”

“Yes, the ditch is the most important thing, just now,” added Woot.

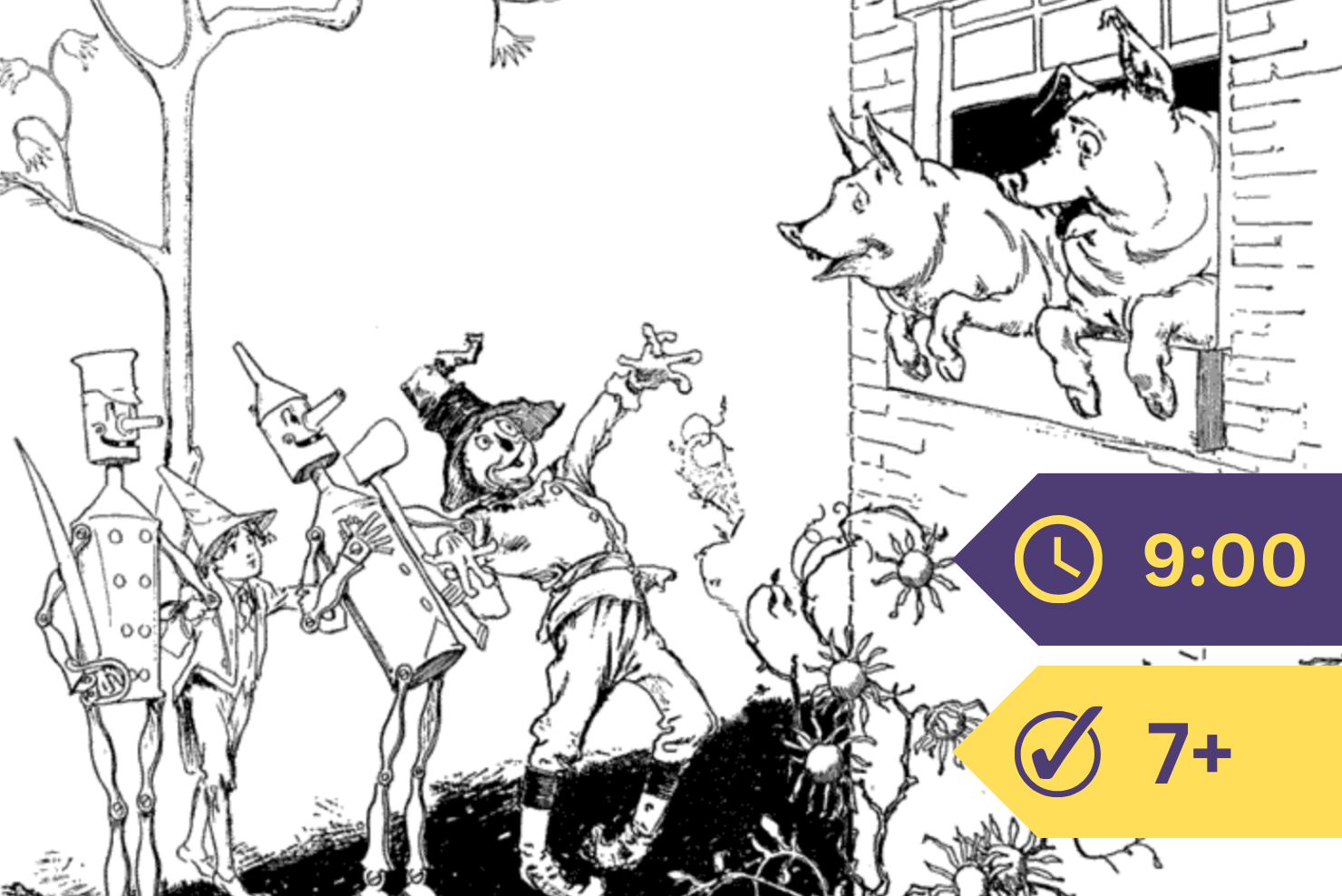

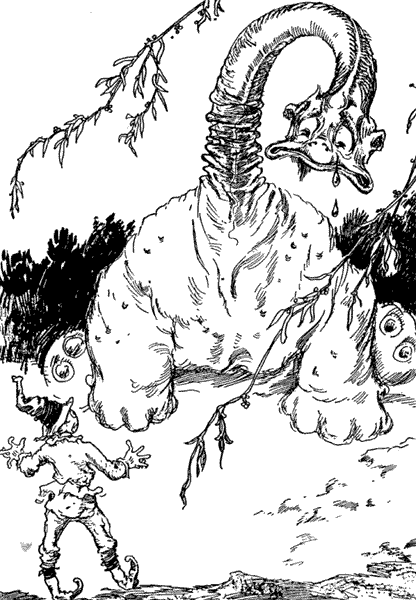

They were standing in a row, looking hard at the unexpected barrier, when a fierce growl from behind them made them all turn quickly. Out of the invisible country marched a huge beast with a thick, leathery skin and a surprisingly long neck. The head on the top of this neck was broad and flat and the eyes and mouth were very big and the nose and ears very small. When the head was drawn down toward the beast’s shoulders, the neck was all wrinkles, but the head could shoot up very high indeed, if the creature wished it to.

“Dear me!” exclaimed the Scarecrow, “this must be the Hip-po-gy-raf.”

“Quite right,” said the beast; “and you’re the straw which I’m to eat for my dinner. Oh, how I love straw! I hope you don’t resent my affectionate appetite?”

With its four great legs it advanced straight toward the Scarecrow, but the Tin Woodman and the Tin Soldier both sprang in front of their friend and flourished their weapons.

“Keep off!” said the Tin Woodman, warningly, “or I’ll chop you with my axe.”

“Keep off!” said the Tin Soldier, “or I’ll cut you with my sword.”

“Would you really do that?” asked the Hip-po-gy-raf, in a disappointed voice.

“We would,” they both replied, and the Tin Woodman added: “The Scarecrow is our friend, and he would be useless without his straw stuffing. So, as we are comrades, faithful and true, we will defend our friend’s stuffing against all enemies.”

The Hip-po-gy-raf sat down and looked at them sorrowfully.

“When one has made up his mind to have a meal of delicious straw, and then finds he can’t have it, it is certainly hard luck,” he said. “And what good is the straw man to you, or to himself, when the ditch keeps you from going any further?”

“Well, we can go back again,” suggested Woot.

“True,” said the Hip-po; “and if you do, you’ll be as disappointed as I am. That’s some comfort, anyhow.”

The travelers looked at the beast, and then they looked across the ditch at the level plain beyond. On the other side the grass had grown tall, and the sun had dried it, so there was a fine crop of hay that only needed to be cut and stacked.

“Why don’t you cross over and eat hay?” the boy asked the beast.

“I’m not fond of hay,” replied the Hip-po-gy-raf; “straw is much more delicious, to my notion, and it’s more scarce in this neighborhood, too. Also I must confess that I can’t get across the ditch, for my body is too heavy and clumsy for me to jump the distance. I can stretch my neck across, though, and you will notice that I’ve nibbled the hay on the farther edge—not because I liked it, but because one must eat, and if one can’t get the sort of food he desires, he must take what is offered or go hungry.”

“Ah, I see you are a philosopher,” remarked the Scarecrow.

“No, I’m just a Hip-po-gy-raf,” was the reply.

Polychrome was not afraid of the big beast. She danced close to him and said:

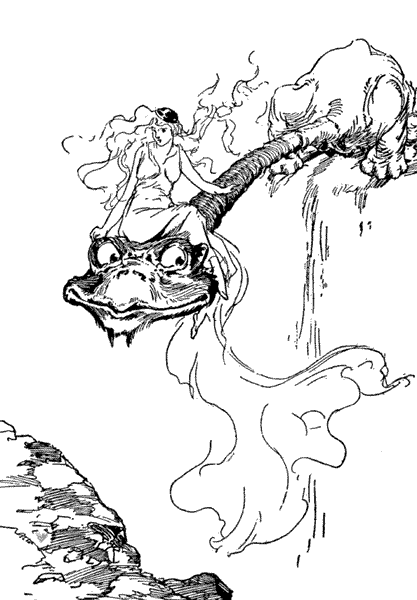

“If you can stretch your neck across the ditch, why not help us over? We can sit on your big head, one at a time, and then you can lift us across.”

“Yes; I can, it is true,” answered the Hip-po; “but I refuse to do it. Unless—” he added, and stopped short.

“Unless what?” asked Polychrome.

“Unless you first allow me to eat the straw with which the Scarecrow is stuffed.”

“No,” said the Rainbow’s Daughter, “that is too high a price to pay. Our friend’s straw is nice and fresh, for he was restuffed only a little while ago.”

“I know,” agreed the Hip-po-gy-raf. “That’s why I want it. If it was old, musty straw, I wouldn’t care for it.”

“Please lift us across,” pleaded Polychrome.

“No,” replied the beast; “since you refuse my generous offer, I can be as stubborn as you are.”

After that they were all silent for a time, but then the Scarecrow said bravely:

“Friends, let us agree to the beast’s terms. Give him my straw, and carry the rest of me with you across the ditch. Once on the other side, the Tin Soldier can cut some of the hay with his sharp sword, and you can stuff me with that material until we reach a place where there is straw. It is true I have been stuffed with straw all my life and it will be somewhat humiliating to be filled with common hay, but I am willing to sacrifice my pride in a good cause. Moreover, to abandon our errand and so deprive the great Emperor of the Winkies—or this noble Soldier—of his bride, would be equally humiliating, if not more so.”

“You’re a very honest and clever man!” exclaimed the Hip-po-gy-raf, admiringly. “When I have eaten your head, perhaps I also will become clever.”

“You’re not to eat my head, you know,” returned the Scarecrow hastily. “My head isn’t stuffed with straw and I cannot part with it. When one loses his head he loses his brains.”

“Very well, then; you may keep your head,” said the beast.

The Scarecrow’s companions thanked him warmly for his loyal sacrifice to their mutual good, and then he laid down and permitted them to pull the straw from his body. As fast as they did this, the Hip-po-gy-raf ate up the straw, and when all was consumed Polychrome made a neat bundle of the clothes and boots and gloves and hat and said she would carry them, while Woot tucked the Scarecrow’s head under his arm and promised to guard its safety.

“Now, then,” said the Tin Woodman, “keep your promise, Beast, and lift us over the ditch.”

“M-m-m-mum, but that was a fine dinner!” said the Hip-po, smacking his thick lips in satisfaction, “and I’m as good as my word. Sit on my head, one at a time, and I’ll land you safely on the other side.”

He approached close to the edge of the ditch and squatted down. Polychrome climbed over his big body and sat herself lightly upon the flat head, holding the bundle of the Scarecrow’s raiment in her hand. Slowly the elastic neck stretched out until it reached the far side of the ditch, when the beast lowered his head and permitted the beautiful fairy to leap to the ground.

Woot made the queer journey next, and then the Tin Soldier and the Tin Woodman went over, and all were well pleased to have overcome this serious barrier to their progress.

“Now, Soldier, cut the hay,” said the Scarecrow’s head, which was still held by Woot the Wanderer.

“I’d like to, but I can’t stoop over, with my bent leg, without falling,” replied Captain Fyter.

“What can we do about that leg, anyhow?” asked Woot, appealing to Polychrome.

She danced around in a circle several times without replying, and the boy feared she had not heard him; but the Rainbow’s Daughter was merely thinking upon the problem, and presently she paused beside the Tin Soldier and said:

“I’ve been taught a little fairy magic, but I’ve never before been asked to mend tin legs with it, so I’m not sure I can help you. It all depends on the good will of my unseen fairy guardians, so I’ll try, and if I fail, you will be no worse off than you are now.”

She danced around the circle again, and then laid both hands upon the twisted tin leg and sang in her sweet voice:

“Fairy Powers, come to my aid!

This bent leg of tin is made;

Make it straight and strong and true,

And I’ll render thanks to you.”

“Ah!” murmured Captain Fyter in a glad voice, as she withdrew her hands and danced away, and they saw he was standing straight as ever, because his leg was as shapely and strong as it had been before his accident.

The Tin Woodman had watched Polychrome with much interest, and he now said:

“Please take the dent out of my side, Poly, for I am more crippled than was the Soldier.”

So the Rainbow’s Daughter touched his side lightly and sang:

“Here’s a dent by accident;

Such a thing was never meant.

Fairy Powers, so wondrous great,

Make our dear Tin Woodman straight!”

“Good!” cried the Emperor, again standing erect and strutting around to show his fine figure. “Your fairy magic may not be able to accomplish all things, sweet Polychrome, but it works splendidly on tin. Thank you very much.”

“The hay—the hay!” pleaded the Scarecrow’s head.

“Oh, yes; the hay,” said Woot. “What are you waiting for, Captain Fyter?”

At once the Tin Soldier set to work cutting hay with his sword and in a few minutes there was quite enough with which to stuff the Scarecrow’s body. Woot and Polychrome did this and it was no easy task because the hay packed together more than straw and as they had little experience in such work their job, when completed, left the Scarecrow’s arms and legs rather bunchy. Also there was a hump on his back which made Woot laugh and say it reminded him of a camel, but it was the best they could do and when the head was fastened on to the body they asked the Scarecrow how he felt.

“A little heavy, and not quite natural,” he cheerfully replied; “but I’ll get along somehow until we reach a straw-stack. Don’t laugh at me, please, because I’m a little ashamed of myself and I don’t want to regret a good action.”

They started at once in the direction of Mount Munch, and as the Scarecrow proved very clumsy in his movements, Woot took one of his arms and the Tin Woodman the other and so helped their friend to walk in a straight line.

And the Rainbow’s Daughter, as before, danced ahead of them and behind them and all around them, and they never minded her odd ways, because to them she was like a ray of sunshine.