The plants about which we read in the last chapter do not take any active part in capturing insects. They set their traps, and then keep quiet. But there are plants which lay hold of their poor victims, and crush the life out of them in a way that seems almost uncanny.

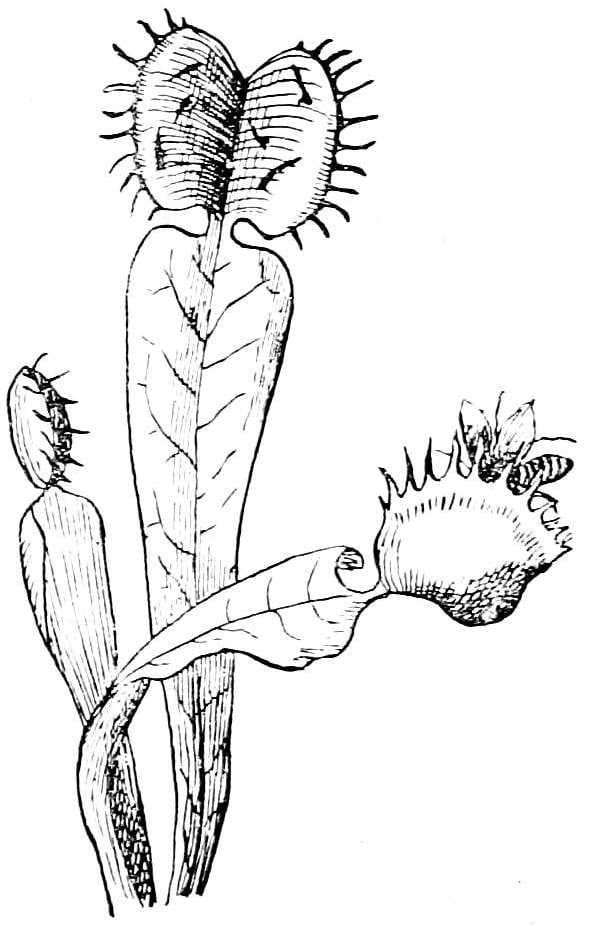

This leaf belongs to a plant which lives in North Carolina. It is called Venus’s flytrap.

You see that the upper, rounded part of the leaf is divided by a rib into two halves. From the edges of these rounded halves run out a number of long, sharp teeth; and three stout bristles stand out from the central part of each half. When an insect alights upon this horrible leaf, the two halves come suddenly together, and the teeth which fringe their edges are locked into one another like the fingers of clasped hands.

The poor body that is caught in this cruel trap is crushed to pieces. Certain cells in the leaf then send out an acid in which it is dissolved, and other cells swallow the solution.

After this performance the leaf remains closed for from one to three weeks. When finally it reopens, the insect’s body has disappeared, and the trap is set and ready for another victim.

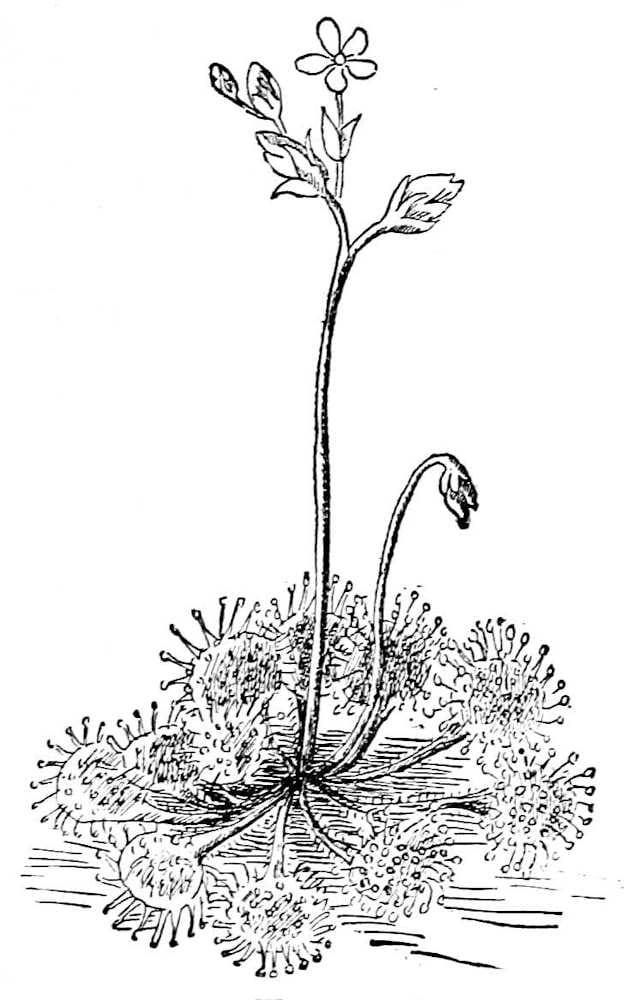

The next picture shows you a little plant which is very common in our swamps,—so common that some of you ought to find it without difficulty next summer, and try upon it some experiments of your own.

It is called the “sundew.” This name has been given to it because in the sunshine its leaves look as though wet with dew. But the pretty drops which sparkle like dew do not seem so innocent when you know their object. You feel that they are no more pleasing than is the bit of cheese in the mouse trap.

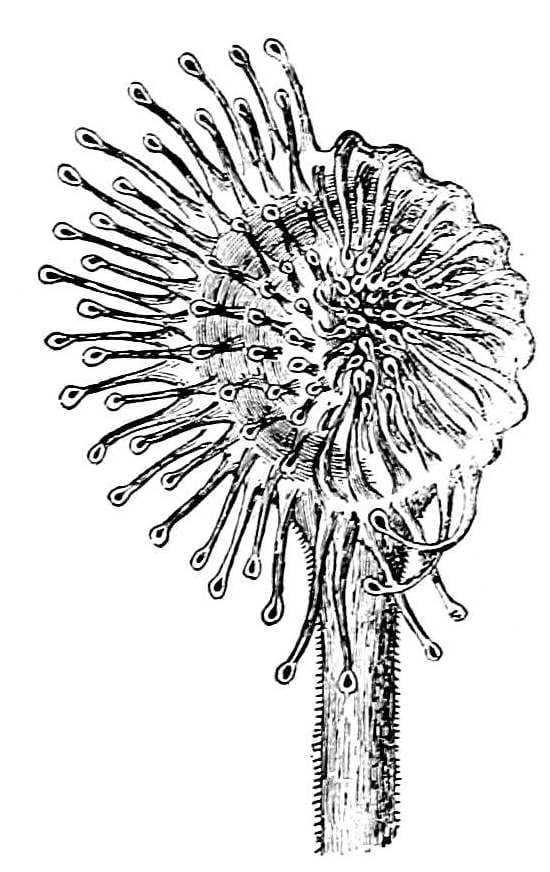

When you see this plant growing in the swamp among the cranberry vines and the pink orchids, you admire its little white flowers, and its round red-haired leaves, and think it a pretty, harmless thing. But bend down and pluck it up, root and all, out of the wet, black earth. Carry it home with you, and, if you have a magnifying glass, examine one of its leaves.

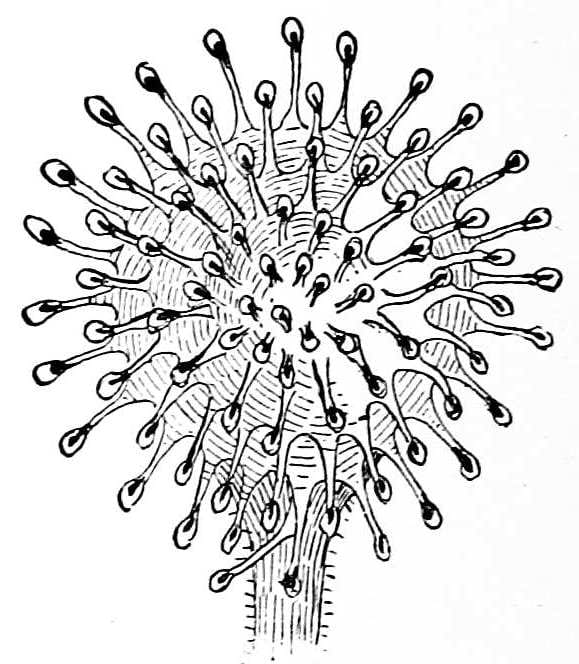

The picture shows you a leaf much larger than it is in life. The red hairs look like pins stuck in a cushion, and the head of each pin glistens with the drop that looks like dew.

But the ants and flies do not take these drops for dew. They believe them to be the sweet nectar for which they long, and they climb or light upon the leaves in this belief.

And then what happens?

The next two pictures will show you.

The red hairs close slowly but surely over the insect whose legs are already caught and held fast by the sticky drops it mistook for nectar, and they hold it imprisoned till it dies and its juices are sucked in by the leaf.

I should like you to satisfy yourselves that these leaves act in the way I have described. But a bit of fresh meat will excite the red hairs to do their work quite as well as an insect, and I hope in your experiments you will be merciful as well as inquiring.

So you see that the little sundew is quite as cruel in its way as the other insect-eating plants. But its gentle looks seem to have deceived the poet Swinburne, who wonders how and what these little plants feel, whether like ourselves they love life and air and sunshine.

“A little marsh-plant, yellow-green

And tipped at lip with tender red,

Tread close, and either way you tread,

Some faint, black water jets between

Lest you should bruise its curious head.

“You call it sundew; how it grows,

If with its color it have breath,

If life taste sweet to it, if death

Pain its soft petal, no man knows,

Man has no sight or sense that saith.”