When a child smells a flower, he is apt to put his nose right into the middle of the blossom, and to take it out with a dab of yellow dust upon its tip.

When he brushes off this dust, of course he does not stop to think that each tiny grain holds a speck of the wonderful material we read about some time ago, the material without which there can be no life.

And probably he does not know that the dust grains from the lily are quite unlike those which he rubs upon his nose when he smells a daisy; that different kinds of flowers yield different kinds of flower dust.

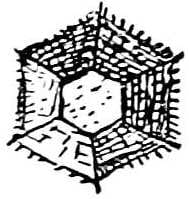

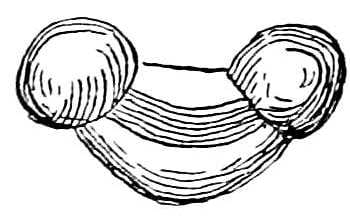

If you should look through a microscope at a grain of flower dust from the lily, you would see an object resembling the picture above.

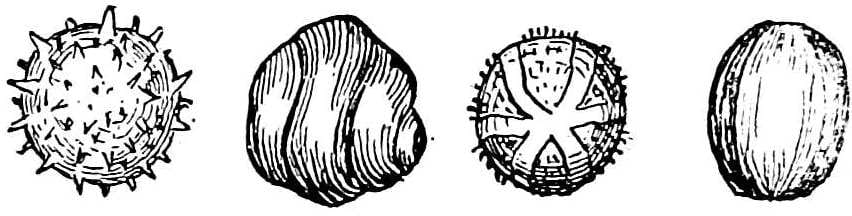

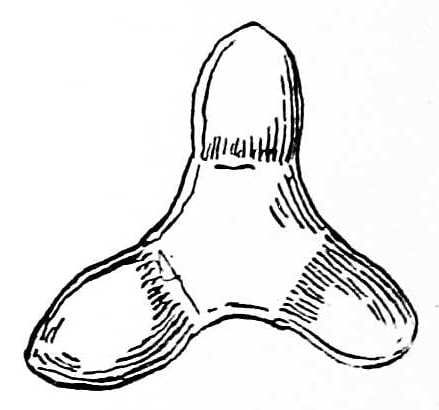

It shows a grain from the pretty blue flower of the chicory. The next picture is a dust grain from the flower of the pine tree. The next one is from the laurel, and the odd-looking is from a dust box of the evening primrose.

The next picture shows you a group of dust grains from flowers of different kinds, one looking like a porcupine, another like a sea shell, another like some strange water animal, and all, I fancy, quite unlike any idea you may have had as to the appearance of a grain of flower dust.

When you are older, I hope it may be your good luck to see through a microscope some of the odd shapes and curious markings of different kinds of flower dust, or “pollen,” as this flower dust is called in the books.

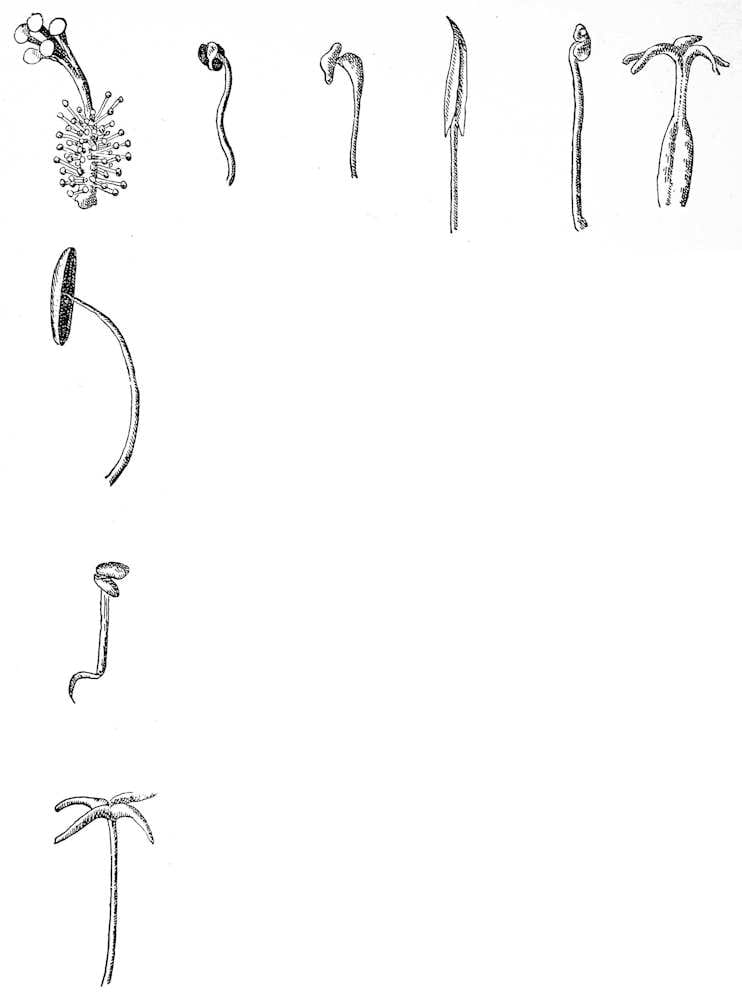

And now that you know something of the appearance of flower dust, perhaps you wish to learn a little more of the way in which it helps the flower to turn into the fruit.