Dorothy was very fond of her grandmother and grandfather, and liked to visit them, but there were no little girls to play with, and sometimes she was lonely for some one her own age. She would wander about the house looking for the queer things that grandmothers always have in their homes. The hall clock interested Dorothy very much. It stood on the landing at the top of the stairs, and she used to sit and listen to its queer tick-tock and watch the hands, which moved with little nervous jumps. Then there were on its face the stars and the moon and the sun, and they all were very wonderful to Dorothy. One day she went into the big parlor, where there were pictures of her grandfather and grandmother, and her great-grandfather and great-grandmother, also.

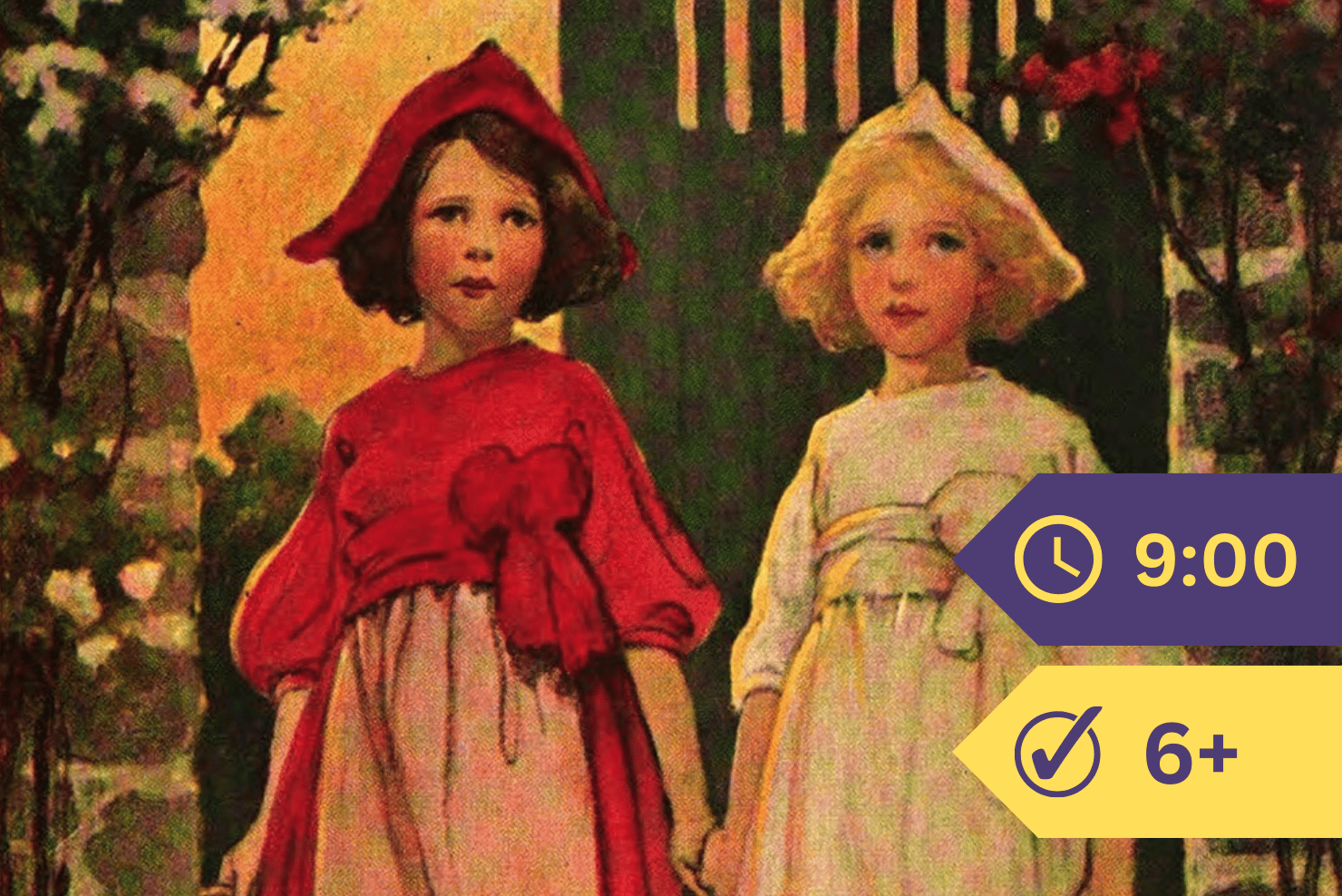

Dorothy thought the “greats” looked very sedate, and she felt sure they must have been very old to have been the parents of her grandfather. But the picture that interested her the most was a large painting of three children, one a little girl about her own age, and one other older, and a boy, who wore queer-looking trousers, cut off below the knee. His suit was of black velvet, and he wore white stockings and black shoes. The little girls were dressed in white, and their dresses had short sleeves and low necks. The older girl had black hair, but the one that Dorothy thought was her age had long, golden curls like hers, only the girl in the picture wore her hair parted, and the curls hung all about her face.

Dorothy climbed into a big chair and sat looking at them. “I wish they could play with me,” she thought, and she smiled at the little golden-haired girl. And then, wonderful to tell, the girl in the picture smiled at Dorothy.

“Oh! are you alive?” asked Dorothy.

“Of course I am,” the little girl replied. “I will come down, if you would like to have me, and visit with you.”

“Oh, I should be so glad to have you!” Dorothy answered.

Then the boy stepped to the edge of the frame, and from there to the top of a big chair which stood under the picture, and stood in the chair seat. He held out his hand to the little girls and helped them to the floor in the most courtly manner. Dorothy got out of her chair and asked them to be seated, and the boy placed chairs for them beside her.

“What is your name?” asked the golden-haired girl, for she was the only one who spoke.

“That was my name,” she said, when Dorothy told her. “I lived in this house,” she continued, “and we used to have such good times. This is my sister and my brother.” The little girl and boy smiled, but they let their sister do all the talking. “We used to roast chestnuts in the fireplace,” she said, “and once we had a party in this room, and played all sorts of games.”

Dorothy could not imagine that quiet room filled with children.

“Do you remember how we frightened poor old Uncle Zack in this room?” she said to her brother and sister, and then they all laughed.

“Do tell me about it,” said Dorothy.

“These glass doors by the fireplace did not have curtains in our day,” said the little girl, “and there were shells and other things from the ocean in one cupboard, and in the other there were a sword and a helmet and a pair of gauntlets. My brother wrapped a sheet around him and put on the helmet and the gauntlets, and, taking the sword in his hand, he climbed into the cupboard and sat down. We girls closed the doors and hid behind the sofa. Uncle Zack came in to fix the fire, and my brother beckoned to him. Poor Zack dropped the wood he was carrying and fell on his knees, trembling with fright. The door was not fastened and my brother pushed it open and pointed the sword at poor Uncle Zack.

“‘You told about the jam the children ate,’ said my brother, in a deep voice, ‘and you know you drank the last drop of rum Mammy Sue had for her rheumatism, and for this you must be punished,’ and he brought the sword down on the floor of the cupboard with a bang.

“Poor Uncle Zack fell on his face with fright. This was too much for my sister and me, and we laughed out.

“You never saw any one change so quickly as Uncle Zack. He jumped up and we ran, but my brother had to get out of his disguise, and Uncle Zack caught him. He agreed not to tell our father if we did not tell about his fright, and so we escaped being punished.”

“Tell me more about your life in this old house,” said Dorothy, when the little girl finished her story. But just then the picture of Dorothy’s great-grandmother moved and out she stepped from her frame. She walked with a very stately air toward the children and put her hand on the shoulder of the little girl who had been telling the story, and said: “You better go back to your frame now.”

“Oh dear!” said the little girl. “I did so dislike being grown up, and I had forgotten all about it, when my grown-up self reminds me. That is the trouble when you are in the room with your grown-up picture,” she told Dorothy. “You see, I had to be so sedate after I married that I never even dared to think of my girlhood, but you come in here again some day and I will tell you more about the good times we had.”

The boy mounted the chair first and helped his sisters back into the frame. Dorothy looked for her great-grandmother, but she, too, was back in her frame, looking as sedate as ever. The next day Dorothy asked her grandmother who the children were in the big picture.

“This one,” she said, pointing to the little golden-haired girl, “was your great-grandmother; you were named for her; and the other little girl and boy were your grandfather’s aunt and uncle. They were your great-great-aunt and uncle.”

Dorothy did not quite understand the “great-great” part of it, but she was glad to know that her stately-looking great-grandmother had once been a little girl like her, and some day, when the great-grandmother’s picture is not looking, she expects to hear more about the fun the children had in the days long ago.