At the officer’s ringing words, King Dad lowered his paper, and as he got a good look at the Hungry Tiger, his chair fell forward with a crash.

“A tiger, Nance!” stuttered Dad, rolling his eyes wildly at the Queen.

“But it’s tied,” answered the Queen of Down Town calmly. “What are the charges, officer?”

“Ninety-nine dollars and sixty-eight cents,” answered the officer hoarsely, and leaning over he handed Dad a long slip of paper.

“But we only wanted a little breakfast,” began Betsy tremulously, “and——”

“A little breakfast!” wheezed Dad, and putting on his specs started to read off the list:

“Twelve roasts,

Four turkeys,

One spring chicken,

Three dozen tarts,

Fourteen doughnuts

One ham and twenty-four biscuits,

Three quarts of potato salad,

One six-pound sausage.”

“Monstrous!” muttered the Queen, tapping her foot indignantly on the floor. “They shall pay well for this.”

“Why, that’s a mere bite for a fellow like me,” rumbled the Hunger Tiger, impatiently, “and I ate most of it.”

“Who—who are you?” demanded Dad, holding on to the arms of his chair and blinking nervously at the great beast.

“I am the Hungry Tiger of Oz, and these are my friends. We are on our way to the Emerald City. This little girl is Betsy Bobbin and allow me to present the Vegetable Man and the Pasha of—”

“Your tale drags,” yawned her Majesty, fanning herself with her handkerchief. “Cut it short. Time is money down here and the thing for you to do is to pay up and settle down.”

“How clearly you put things,” murmured Dad, looking affectionately at his Queen. Betsy had been staring at Her Highness in perfect astonishment, for she was made entirely of money. Her face and hair were of purest gold, her hands and feet of silver and her dress was made from hundreds of yellow bills that crinkled crisply when she moved. Yet, with all her glitter and brilliance, she seemed to Betsy the hardest and most disagreeable being she had ever met. Dad, himself looked kind and care-worn, resembling vaguely many of the daddies Betsy had known in the United States. If he had just decided things for himself and not depended so much upon the Queen, Betsy would have liked him better.

“Well, are you ready to pay up?” asked Dad, looking from one to the other of the travellers. “Ninety-nine dollars and sixty-eight cents, please.”

“But we haven’t any money,” explained Betsy breathlessly. “We started off in such a hurry and—”

“You should not have come Down Town if you had no money,” muttered Dad reprovingly.

“How dare you be without money?” cried the Queen, springing up in a perfect fury. “How dare you come Down Town without money?”

“Now, don’t get frenzied, Fi Nance,” begged Dad, patting her anxiously on the hand. “They can easily make some money, you know.” His words seemed to soothe the Queen.

“That’s so,” she mused thoughtfully. “Anybody can make money Down Town, if they just try hard enough.” Almost pleasantly she turned to Betsy. “You, my child,” purred the Queen, resuming her seat, “you, may start as a cash girl. I myself was a cash girl once,” she went on dreamily, “and now look at me—Fi Nance, Queen of Down Town. I’m simply made of money!”

Betsy looked, and shuddered a little as she did so. She was about to tell the Queen that she had no desire to be a cash girl, when Fi Nance haughtily held up her hand for silence. “The lad shall be an office boy,” she decided imperiously. “Who did you say he was?”

“A Prince,” growled the Hungry Tiger.

“A dry goods store will be the best place for him,” murmured Dad. “What can you two do?” he demanded, looking over his specs at the barber and sad singer of Rash.

“Anything! Anything!” whined the frightened prisoners, bumping their heads together in their anxiety to please.

“Pooh!” sniffed Dad scornfully. “That means nothing whatsoever.”

“Shampoo?” suggested the barber hopefully. “Let me give your Highness a little shave and hair cut.”

“Are you a barber?” asked Dad, looking at the Rasher with more interest. “If you’re a barber, you can stay and welcome. There’s always room for another barber, Down Town.”

“Thank you! Thank you! If your majesty will permit—” The barber bowed apologetically to the Prince of Rash, “I will remain here. I have always wanted to make money,” he acknowledged frankly.

“Me too!” gulped the sad singer eagerly.

“I’ve sung until I’m hoarse, in Rash,

And never earned a cent in cash!”

“He has a voice like a horse,” whispered Dad, in a loud aside to the Queen.

“He sings like a jack-ass!” agreed Her Majesty readily. “But let him stay. Any kind of a noise goes, Down Town. Now as to these others?” She rolled her golden eyes in perplexity and disapproval at the Vegetable Man and the Hungry Tiger; then evidently giving them up, cried in a loud voice, “The audience is over and the prisoners are discharged. Let them make some money, pay up and settle down.”

“Well, good-bye!” smiled Dad, picking up his paper with a sigh of relief. “If you don’t like the positions we have chosen for you, go down to the square and choose some others. Take them to the public square!” he ordered, waving at the officers.

So, much to Betsy’s and the little Prince’s amusement, they were all hurried into the elevator, out of the bank and marched along the streets of the city. A curious sign on the first corner puzzled Betsy very much.

“Down Town belongs to the Daddies,” said the sign severely, “No aunts, mothers or sisters allowed.”

“Why, anybody can go down town at home,” exclaimed the little girl in surprise.

“I noticed there were no ladies about,” observed Carter in an amused voice. “The Daddies have it all their own way here.”

As they passed along, Betsy looked curiously in the windows of the shops and offices and saw that everywhere the Dads were making money. Some were making money out of leather, some were making money out of oil and some were even making money out of old papers and rags. It looked quite simple.

“But there must be some trick to it,” she whispered hurriedly to the Prince of Rash. “I hope we don’t have to stay here long. I won’t be a cash girl.”

Prince Evered nodded emphatically, for he had no intention of becoming an office boy. Just then they came to the public square and were marched solemnly through the gates.

“Pick your tools and get started,” ordered the first officer gruffly, and grumbling a little among themselves, because the prisoners had got off so easily, the twenty tall Downsmen tramped noisily back to their station. As soon as they had gone, the barber, with his razor, released the Hungry Tiger from the net.

“I wonder what they meant about tools,” murmured Betsy, staring all around her. “Why what an enormous tree!” It stood in the center of the square, spreading out in every direction, its branches weighted down with a most curious collection of objects. There was a small notice tacked on the trunk and Evered and Betsy Bobbin hurried over to investigate.

“Indus Tree,” read the sign. “Pick your trade, business or profession here.”

“Well, I’ve often heard of the big industries,” gasped Carter Green, squinting up through the branches, “but I never knew they looked like this. If we are to stay Down Town, I suppose we had better pick our business at once.”

“Stay if you want to,” rumbled the Hungry Tiger impatiently. “My business is to see that Betsy Bobbin gets safely back to Oz and to restore Reddy to his throne. I, for my part, am going to leave as soon as I can find an exit.”

“Maybe they won’t let us,” faltered Betsy, looking uneasily over her shoulder. But the Daddies were not paying the slightest attention to the little group in the square and, greatly relieved, they turned back to the Indus Tree.

“Some of these things might prove useful, even if we did not remain here,” muttered Carter.

“Why, there’s a razor!” shouted the Rash barber in delight, and springing into the air, he snapped it off the lower branch and began to finger it lovingly.

“I’d take that harp, if I could just reach it,” sighed the sad singer, looking wistfully aloft.

“I’ll pick it for you,” offered Prince Evered obligingly, and swinging up into the tree he broke the harp from its stem and dropped it into the singer’s arms.

“See anything you want, Betsy?” called the little Prince, and pushing aside a cluster of paint brushes, he peered down at her expectantly. But with so many things to choose from, it was hard to decide. There were thimbles and shears, bottles of ink, hammers, saws, buckets and mops, brooms and hoes, music rolls, miners’ caps, rolling pins, cook books, compasses and ship models—everything in fact that a body would need to work with.

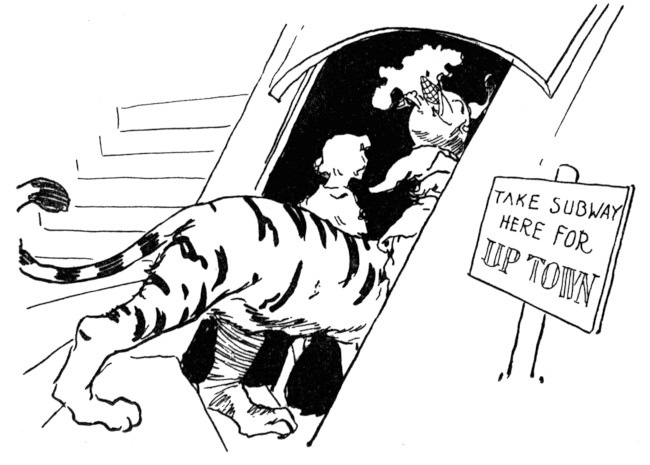

While Reddy was waiting for Betsy to make up her mind, his curiosity carried him higher and higher into the branches. Carter, too, walked round and round the base of the tree, shaking his head and exclaiming from time to time with surprise and astonishment. But the Hungry Tiger had small use for a tree that produced nothing to eat, nor was he interested in money or making money. So, while the others examined the marvelous tree, he began looking for a way out, and presently was rewarded, for in the far corner of the square were steps leading down into what seemed to be a tunnel. Stretching his neck cautiously about the doorway, the Hungry Tiger spied some directions.

“Take the subway here for Up Town,” said a sign.

“Here! Here! I’ve found a way out!” roared the Hungry Tiger joyfully.

“What kind of a way?” cried Carter, stumbling over the wheel-barrow he had just plucked from the Indus Tree.

“A subway!” puffed the tiger. “Tell the rest of ’em, quick!”

“Come on! Come on!” cried Carter waving to the others. “The Hungry Tiger has found some way out.”

“I said, ‘subway!'” growled the tiger a bit temperishly. “Are you going to take that thing along with you?” The Vegetable Man looked lovingly at the wheel-barrow.

“It was the nearest thing to a cart I could find,” he murmured sadly, “and will come in very handy if I pick up some vegetables or fruit. So will this.” He patted a small spade that had grown on the same branch with the wheel-barrow. “Hello, here they come now!” At Carter’s cries, the little Prince of Rash, who had been trying to decide between a policeman’s club and a sword, plucked the sword and came crashing to earth, followed by several bottles of ink and an ironing board.

“I may have to fight for my Kingdom,” he told Betsy importantly, “and this sword will help.” Betsy nodded understandingly, and without waiting to pick anything for herself she ran over to the Hungry Tiger. They were all anxious to leave Down Town, and when Betsy told them a little about subways (she had often been in subways in the United States) the Hungry Tiger gave the signal to start.

“We’ve forgotten the barber and the singer,” exclaimed Betsy, pausing suddenly on the top step. But just then the two Rashers came hurrying over, and when the Hungry Tiger announced that they were going Up Town and from there back to the Marvelous Land of Oz, both drew back.

“I’ve had enough ups and downs in my life,” sighed the barber, “and will remain here and make my fortune. By that time Prince Evered may, perchance, be restored to his throne. Then and then only will I return to Rash.” The singer, after one look into the gloomy opening, declared that he too, preferred to stay Down Town.

“With this harp and my beautiful voice, I will soon be a rich man,” he assured them earnestly, and with many goodbyes and good wishes the four travellers left them to make their fortunes. Long after they had descended the steps and entered the subway itself, they could hear the plaintive wails of the sad singer and the thrum of the harp he had picked from the Indus Tree.

It was dim and mysterious in the underground passageway, and after looking in vain for a car or train to carry them Up Town, Betsy began following the arrows painted on the white washed walls.

“There ought to be a car somewhere,” panted the little girl, after they had made at least fifty turns.

“Try mine,” invited Carter, and with a tired smile Betsy dropped into the wheel-barrow. Reddy was riding the Hungry Tiger, and after they had proceeded for more than an hour, the arrows stopped altogether.

“Well, this isn’t like our subways at all,” exclaimed Betsy in disgust. “When you take a subway at home, you get somewhere.”

“Isn’t this somewhere?” asked Carter, stooping a little so he could enter a rough stone cavern at the end of the tunnel. Whistling cheerfully, he trundled Betsy through the low doorway. The Hungry Tiger followed, sniffing the air suspiciously, and it must be confessed that the little rock chamber did not look very inviting. The walls were of jagged gray stone, the floor damp and slippery and the whole place dismal and chilly as a vault. A feeble light flickered down from an opening in the ceiling and after a discouraged look round, Betsy shook her head.

“We’ll have to go back Down Town,” she sighed sadly. “I’ll have to be a cash girl after all!”

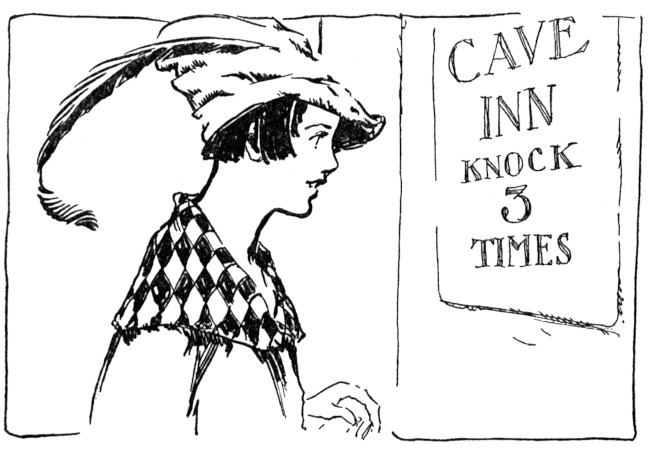

“No you won’t!” called Reddy. He had jumped off the tiger and gone to examine the back of the cavern. “Here’s a door!” Hurrying over, the others saw that the little Prince was right.

“‘Cave Inn,'” roared the Hungry Tiger, reading the door plate over the little boy’s shoulder. “‘Knock three times.’ Why, that’s fine! If it’s an Inn, they’ll surely have something to eat. We can’t get out so we might as well go in,” he finished with a playful wink at Carter. Stepping back a few paces, the Hungry Tiger ran at the door and bumped his head three times against the brass plate. At the third bump, the door of Cave Inn flew open, the floor of the cave itself, tilted forward and the four adventurers fell through. Stones and dirt rattled down after them and the Hungry Tiger’s growls mingled with the screams of Betsy and Evered, as they went tumbling down into the darkness.