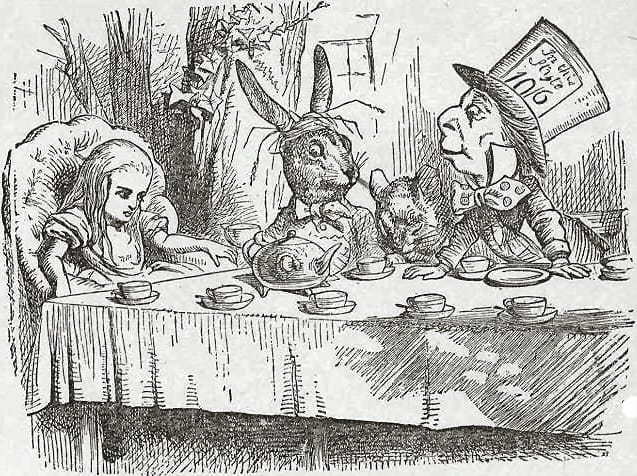

There was a table set out, in the shade of the trees in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were at tea; a Dormouse sat between them, but it seemed to have gone to sleep. The table was a long one, but the three were all crowded at one corner of it. “No room! No room!” they cried out as soon as they saw Alice. “There’s plenty of room,” she said, and sat down in a large armchair at one end of the table.

“Have some wine,” the March Hare said in a kind tone.

Alice looked all round the table, but there was not a thing on it but tea. “I don’t see the wine,” she said.

“There isn’t any,” said the March Hare.

“Then it wasn’t polite of you to ask me to have wine,” said Alice.

“It wasn’t polite of you to sit down when no one had asked you to have a seat,” said the March Hare.

“I didn’t know it was your table,” said Alice; “it’s laid for more than three.”

“Your hair wants cutting,” said the Hatter. He had looked hard at Alice for some time, and this was his first speech.

“You should learn not to speak to a guest like that,” said Alice; “it is very rude.”

The Hatter stretched his eyes quite wide at this; but all he said was, “Why is a raven like a desk?”

“Come, we shall have some fun now,” thought Alice. “I think I can guess that,” she added out loud.

“Do you mean that you think you can find out the answer to it?” asked the March Hare.

“I do,” said Alice.

“Then you should say what you mean,” the March Hare went on.

“I do,” Alice said; “at least—at least I mean what I say—that’s the same thing, you know.”

“Not the same thing a bit!” said the Hatter. “Why, you might just as well say, ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as ‘I eat what I see’!”

“You might just as well say,” added the March Hare, that ‘I like what I get’ is the same thing as ‘I get what I like’!”

“You might just as well say,” added the Dormouse, who seemed to be talking in his sleep, “that ‘I breathe when I sleep’ is the same thing as ‘I sleep when I breathe’!”

“It is the same with you,” said the Hatter.

No one spoke for some time, while Alice tried to think of all she knew of ravens and desks, which wasn’t much.

The Hatter was the first to speak. “What day of the month is it?” he said, turning to Al-ice. He had his watch in his hand, looked at it and shook it now and then while he held it to his ear.

Alice thought a-while, and said, “The fourth.”

“Two days wrong!” sighed the Hatter. “I told you butter wouldn’t suit this watch,” he added with a scowl as he looked at the March Hare.

“It was the best butter,” the March Hare said.

“Yes, but some crumbs must have got in,” the Hatter growled; “you shouldn’t have put it in with the breadknife.”

The March Hare took the watch and looked at it; then dipped it into his cup of tea and looked at it again; but all he could think to say was, “it was the best butter, you know.”

“Oh, what a funny watch!” said Alice. “It tells the day of the month and doesn’t tell what o’clock it is!”

“Why should it?” growled the Hatter.

“Does your watch tell what year it is?”

“Of course not,” said Alice, “but there’s no need that it should, since it stays the same year such a long time.”

“Which is just the case with mine,” said the Hatter; which seemed to Alice to have no sense in it at all.

“I don’t quite know what you mean,” she said.

“The Dormouse has gone to sleep, once more,” said the Hatter, and he poured some hot tea on the tip of its nose.

The Dormouse shook its head, and said with its eyes still closed, “Of course, of course; just what I wanted to say myself.”

“Have you guessed the riddle yet?” the Hatter asked, turning to Alice.

“No, I give it up,” she said. “What’s the answer?”

“I do not know at all,” said the Hatter.

“Nor I,” said the March Hare.

Alice sighed. “I think you might do better with the time than to waste it, by asking riddles that have no answers.”

“If you knew Time as well as I do, you wouldn’t say ‘waste it.’ It’s him.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” Alice said.

“Of course you don’t!” said the Hatter with a toss of his head. “I dare say you never even spoke to Time.”

“Maybe not,” she said, “but I know I have to beat time when I learn to sing.”

“Oh! that’s it,” said the Hatter. “He won’t stand beating. Now if you kept on good terms with him, he would do anything you liked with the clock. Say it was nine o’clock, just time to go to school; you’d have but to give a hint to Time, and round goes the clock! Half-past one, time for lunch.”

“I wish it was,” the March Hare said to itself.

“That would be grand, I’m sure,” said Alice: “but then—I shouldn’t be hungry for it, you know.”

“Not at first, perhaps, but you could keep it to half-past one as long as you liked,” said the Hatter.

“Is that the way you do?” asked Alice.

The Hatter shook his head and sighed. “Not I,” he said. “Time and I fell out last March. It was at the great concert given by the Queen of Hearts and I had to sing:

‘Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!

How I wonder what you’re at!’

You know the song, per-haps?”

“I’ve heard something like it,” said Alice.

“It goes on, you know,” the Hatter said, “in this way:

‘Up above the world you fly,

Like a tea-tray in the sky,

Twinkle, twinkle——'”

Here the Dor-mouse shook itself and sang in its sleep, “twinkle, twinkle, twinkle, twinkle——” and went on so long that they had to pinch it to make it stop.

“Well, while I sang the first verse,” the Hatter went on, “the Queen bawled out ‘See how he murders the time! Off with his head!’ And ever since that, he won’t do a thing I ask! It’s always six o’clock now.”

A bright thought came into Alice’s head. “Is that why so many tea things are put out here?” she asked.

“Yes, that’s it,” said the Hatter with a sigh: “it’s always tea-time, and we’ve no time to wash the things.”

“Then you keep moving round, I guess,” said Alice.

“Just so,” said the Hatter; “as the things get used up.”

“But when you come to the place where you started, what do you do then?” Alice dared to ask.

“I’m tired of this,” yawned the March Hare. “I vote you tell us a tale.”

“I fear I don’t know one,” said Al-ice.

“I want a clean cup,” spoke up the Hatter.

He moved on as he spoke, and the Dormouse moved into his place; the March Hare moved into the Dor-mouse’s place and Alice, none too well pleased, took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the on-y one to get any good from the change; and Alice was a good deal worse off, as the March Hare had upset the milkjug into his plate.

“Now, for your story,” the March Hare said to Alice.

“I’m sure I don’t know,”—Alice began, “I—I don’t think—”

“Then you shouldn’t talk,” said the Hatter.

This was more than Alice could stand; so she got up and walked off, and though she looked back once or twice and half hoped they would call after her, they didn’t seem to know that she was gone. The last time she saw them, they were trying to put the poor Dormouse head first into the teapot.

“Well, I’ll not go there again,” said Alice as she picked her way through the wood. “It’s the dullest tea-par-ty I was ever at in all my life.”

As Alice said this, she saw that one of the trees had a door that led right into it. “That’s strange!” she thought; “but I haven’t seen a thing today that isn’t strange. I think I may as well go in at once.” And in she went.

Once more she found herself in a long hall, and close to the little glass stand. She took up the little key and unlocked the door that led to the gar-den. Then she set to work to eat some of the mushroom which she still had with her. When she was about 30 centimeters high, she went through the door and walked down the little hall; then—she found herself, at last, in the lovely garden, where she had seen the bright blooms and the cool fountains.