Once upon a time in Yedo, there lived a samurai named Hagiwara. He was a samurai of the Hatamoto, which is the most honorable of all ranks of the samurai. He had a noble figure and a very handsome face. He was loved by many women in Yedo, openly and in secret. Because he himself was still very young, his thoughts were only on having fun, rather than on love. And in the morning, afternoon, and evening, he was accustomed to enjoying himself with the young men of the city. He was the prince and leader of joyous parties held both indoors and outdoors. He often paraded long through the streets with his companions.

On a bright winter day, during the New Year festival, he found himself in the company of laughing boys and girls playing a racket game. He had wandered far from his own district in the city and was now in a suburb on the other side of Yedo. Here the streets were more or less empty, and the silent houses were surrounded by gardens. Hagiwara swung his heavy racket with great skill and grace to catch the gilt shuttle and lightly toss it up again. But with a poorly judged stroke, he hit the shuttle over the heads of the players and over the bamboo fence of a nearby garden.

Immediately, he wanted to go after the shuttle. But his friends called out, “Stay here, Hagiwara, we have more than a dozen other shuttles.”

“No,” said Hagiwara, “this shuttle was pigeon-colored and gilt.”

“You foolish man,” his friends replied, “we have six other pigeon-colored and gilt shuttles here.”

But he paid no attention, for he had become filled with a very strange desire for the shuttle he had lost. He climbed over the bamboo fence and fell into the garden on the other side of the fence. Now he had found exactly the spot where the shuttle must have fallen, but there was no shuttle in sight. So he searched at the foot of the bamboo fence – but no, he could not find the shuttle.

Up and down he went, swinging aside the bushes with his racket. He kept his eyes on the ground, breathing heavily as if he had lost his treasure. His friends called to him, but he did not come, and when they grew tired, they went home.

The daylight began to fade. Hagiwara, the samurai, looked up and saw a girl standing a few meters away from him. She beckoned him with her right hand, in her left hand she held the gilt shuttle with pigeon-colored feathers. The samurai cried out with joy and ran forward. Then the girl drew back from him while still beckoning him with her right hand. The shuttle lured him and he followed her. So the two of them went on until they came to the house that stood in the garden. Three stone steps led to the entrance.

Next to the lowest step grew a plum tree in bloom. On the top step stood a virtuous and very young lady. She was beautifully dressed in festival garments. Her kimono was of water-blue silk, with ceremonial sleeves so long that they almost touched the ground. Her underskirt was scarlet, her wide brocade belt was stiff and heavy with gold. When Hagiwara saw the lady, he immediately knelt and paid her deep homage, until his forehead touched the ground.

Then the Lady spoke, smiling with the pleasure of a child. “Come into my house, Hagiwara Sama, samurai of Hatamoto. I am O’Tsuyu, the Lady of the Morning Dew. My dear servant, O’Yone, has brought you to me. Come inside, Hagiwara Sama, samurai of Hatamoto; for I am indeed glad to see you, happy is this hour.” So the samurai went inside. They took him to a room with ten mats, where they entertained him. The Lady of the Morning Dew danced for him in the traditional way, while O’Yone, the servant, beat a small scarlet drum with tassels.

Then they set food before him, the red rice of the festival and sweet warm wine. He ate of the food and drank of the drink they offered him. It was deep in the night when Hagiwara took his leave. “Come again, honorable Sir, come again,” said O’Yone, the servant.

“Yes, Sir, you must come again,” whispered the Lady of the Morning Dew. The samurai laughed. “And what if I do not return?” he said in jest. “What if I do not come back?” The Lady froze and her childish face turned grey but she laid her hand on Hagiwara’s shoulder. “Then,” she said, “Death will be there, Sir. It will mean death for you and me. There is no other way.” O’Yone shook her head and hid her eyes with her sleeve.

The samurai went into the night, very afraid. Long, long he sought his home but could not find it, wandering in the black darkness through the whole sleeping city. When he finally reached his familiar door, the late dawn was almost breaking. Weary, he threw himself upon his bed. Then he laughed. “In the end, I have left my shuttle behind too,” said Hagiwara, the samurai.

The next day Hagiwara was alone at home from morning till evening. He held his hands before him and thought. He did nothing else. At the end of the time he said: “It is a joke that a few geishas have played upon me. Excellently done but they will not catch me.” He put on his finest clothes and went out to join his friends. For five or six days he roamed, the merriest of the young men.

Then he said: “By the Gods, I am sick of this,” and he began to walk alone through the streets of Yedo. He walked from the beginning of the city to the end of the city. He roamed day and night, through streets and lanes, over hills and canals and across the castle wall, but he could not find what he sought.

He could not reach the garden where he had lost his shuttle, nor the Lady of the Morning Dew. His mind had no rest. He became ill and went to bed. He ate neither slept and became ghostly thin. This was about the third month.

In the sixth month, during niubai, the hot rainy season, he stood up and, despite everything his faithful servant tried to say or do to dissuade him, he wrapped a loose summer coat around himself and immediately set out. “Alas, alas,” moaned the servant, “the boy has a fever or he may have gone mad.” Hagiwara had no doubt. He looked neither to the right nor to the left, for he said to himself, “All roads lead past the house of my Beloved.” Soon he arrived in a quiet suburb, at a certain house with a bamboo gate to the garden. Hagiwara laughed softly and climbed the gate. “It will be the same, our meeting will be exactly the same,” he said.

But he found the garden wild and overgrown. Moss covered the three stone steps. The plum tree that grew there fluttered desolately with its green leaves. The house was quiet, the shutters were closed. It was lost and abandoned. The samurai grew cold as he stood there wondering what had happened. A drenching rain fell. Then an old man came into the garden. He said to Hagiwara, “Sir, what are you doing here?”

“The white blossoms have fallen from the plum tree,” said the samurai. “Where is the Lady of the Morning Dew?”

“She is dead,” the old man replied, “for five or six months now, from a strange and sudden illness. She lies in the cemetery on the hill. O’Yone, her servant, lies beside her. She could not bear to leave her mistress to wander alone through the long night of Yomi. For the sake of their sweet spirits, I still tend this garden, but I am old and can do little. Oh sir, they are indeed dead. Grass grows on their graves.”

Hagiwara returned to his own house. He took a piece of pure white wood and wrote the Lady’s name on it, in large honorable characters. He placed the wood down and burned incense and sweet scents before it. He made every imaginable offering and observed it, all for the well-being of her departed spirit.

Then came the festival of Bon, the time of the returning Souls. The Good People of Yedo carried lanterns and visited their graves. They brought food and flowers and tended to their beloved dead.

On the thirteenth day of the seventh month, which, in the Bon, is the day of days, Hagiwara the samurai walked into his garden in search of some coolness in the evening.

It was calm and dark. Occasionally a cicada sang shrilly, hidden in the heart of a pomegranate flower. Here and there a carp jumped in the pond. Otherwise, it was still, and not a leaf stirred. Around the hour of the Ox, Hagiwara heard the sound of footsteps in the lane that ran along his garden hedge. The footsteps came closer and closer. “Those are women’s footsteps,” said the samurai. He recognized them by their hollow echoing sound.

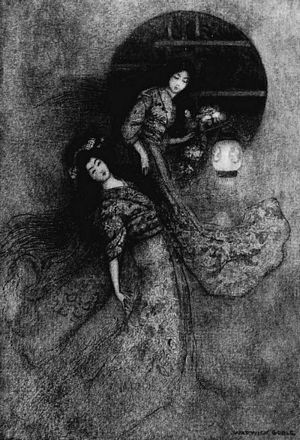

As he looked over his rose hedge, he saw two women, hand in hand, coming out of the darkness. One of the women carried a lantern with a bunch of peonies tied to the handle. It was just such a lantern as was used at the time of the Bon, as a tribute to the dead. The lantern swung back and forth as the two women walked and spread a faint light. When they reached the other side of the hedge, at the samurai’s level, they turned their faces towards him. He recognized them immediately and cried out.

The girl with the peony lantern held the lantern high so that the light fell upon him.

“Hagiwara Sama,” she cried, “of all that is most wonderful, this is the most wonderful! Why, Lord, were we told you were dead? For many moons we recited the Nembutsu for your soul every day.”

“Come in, come in, O’Yone,” he said. “Is it truly your mistress who holds your hand? Can it really be my Lady? …Oh, my dearest!”

O’Yone replied: “Who else could it be?” The two entered through the garden gate. But the Lady of the Morning Dew held up her sleeve to hide her face. “How did I lose you?” said the samurai. “How did I lose you, O’Yone?”

“Lord,” she said, “we moved to a small house, a very small house, in a district of the city called the Green Hill. We were not allowed to take anything with us, we became very poor. My mistress has grown very pale with grief.” Then Hagiwara gently took hold of the woman’s sleeve to pull it back from her face. “Lord,” she sobbed, “you will not love me, I am not honest.”

But when he looked at her, his love for her blazed up in him like a consuming fire, making him tremble from head to toe. He still said nothing.

She knelt down. “Lord,” she murmured, “shall I go or stay?” And he said: “Stay.”

Just before dawn, the samurai fell into a deep sleep, and when he woke up, he was alone in the bright morning light. He did not lose a second, but got up and left. He immediately took the road through Yedo that led to the district of the Green Hill. There he inquired for the house of the Lady of the Morning Dew, but no one could lead him there. He searched everywhere in vain, high and low. It seemed that he had lost his beloved Lady for the second time, and he returned home in despair.

His way led him across the grounds of a certain temple, and as he walked, he noticed two graves that lay side by side. One grave was small and dark, but the other was marked by an honorable monument, like that of an important person. Before the monument hung a lantern, with a bouquet of peonies tied to the handle. It was one of those lanterns that were used in the time of the Bon to serve the dead.

The samurai stood still for a long, long time, as if in a dream. Then he smiled a little and said:

“We moved to a small house, a very small house, on the Green Hill, where we could not take anything with us, we became very poor….my mistress has grown very pale with grief…” He said, “A small house, a dark house, make room for me, oh my beloved, those are my desires. We have loved each other for the duration of ten lives. Do not leave me now, my dearest.” Then he went home. His faithful servant met him and wailed, “Master, what is wrong?” He said, “Why? There is nothing wrong…I have never been so happy.”

But the servant left crying as he said, “The sign of death is visible on his face…and what about me, who raised him in my arms as if he were my own child. Every night, for seven nights, the girls with the peony lantern came to Hagiwara’s house. It didn’t matter what kind of weather it was. They came at the hour of the Ox. It was true mysticism. Through the strong bond of illusion, the living and the dead were connected.

On the seventh night, the samurai’s servant, awake with fear and sadness, looked through a crack in the wooden shutters into his Master’s room. His hair stood on end and his blood ran cold when he saw Hagiwara in the arms of a terrifying creature, smiling at the horrible face and stroking the damp green robe with his fingers.

When day came, the servant went to a holy man who had knowledge of these things. After telling his story, he asked the man if there was any hope left for Hagiwara-sama. “Unfortunately,” said the holy man, “who is able to withstand the power of Karma? Nevertheless, there is a very small hope.” He told the servant what to do.

Before nightfall, he had placed a holy text above each door and window of his Master’s house. He had also rolled a golden emblem of the Tathagata in the silk of his Master’s belt. When these things were done, the Master was first pulled in two directions but then he became himself again, even though he was as weak as water. The servant took him in his arms and laid him on his bed, gently covering him. He saw his Master fall into a deep sleep.

During the hour of the Ox, there was the sound of footsteps in the lane outside the garden hedge. The footsteps came closer and closer. Then they slowed down and stopped. “What does this mean, O’Yone, O’Yone,” asked a pitiful voice. “The house sleeps and I do not see my Lord.”

“Come, let’s go home, dear Lady, Hagiwara’s heart has changed.”

“That cannot be true, O Yone, O’Yone…. you must find a way to bring me to my Lord.”

“Lady, we cannot come in here. See the holy scripture above each door and above each window. We may not enter here.”

Then there was the sound of bitter weeping and a long lament. “Lord, I have loved you for the length of ten lives.” Then the footsteps disappeared and the echo died away.

The same thing happened the next night. Hagiwara slept in weakness, his servant watched over him, the spirits came and went in sobbing despair. On the third day, when Hagiwara took a bath, the emblem was stolen by a thief. The golden emblem of Tathagata, from his belt.

Hagiwara did not notice it. But that night he did stay awake. This time his servant slept, exhausted from the watching. Soon it started raining hard. Hagiwara heard the sound of rain on the roof. The sky had opened up and it rained for hours. The rain wiped away the text above the round window of Hagiwara’s room. At the hour of the Ox, footsteps were heard in the lane that ran along the garden hedge. The footsteps came closer and closer. Then they slowed down and stopped.

“This is the last time, O’Yone, O’Yone, bring me to my Lord. Think of the love of ten lives. The power of Karma is great. There must be a way….”

“Come, my Beloved,” Hagiwara cried out loudly.

“Open the door, my Lord, open it and I will come.”

But Hagiwara could not rise from his seat.

“Come, my Beloved,” he called out for the second time.

“I cannot come, although separation cuts through me like a sharp sword. So we suffer for the sins of a past life.” Thus spoke the Lady of the Morning Dew and moaned like the lost soul she was. But O’Yone took her by the hand. “Look at the round window,” she said.

Then they rose up from the earth together, as if in a breath. Like a scent that drifts in through an open window. The samurai called out for the third time: “Come in, my Beloved.”

As an answer, he heard: “I am coming, my Lord.”

In the gray light of dawn, Hagiwara’s servant found his master cold and dead. At his feet stood a peony lantern, burning with a strange yellow flame. The servant shuddered, picked up the lantern, and blew out the flame while saying: “I cannot bear this.”